ARTS

Exhibitions

The Venice Biennale (Venice, till 27 September)

Dearth in Venice

Giles Auty

Anight fell I followed three myste- rious, jewel-laden women down one of the typically narrow streets which ran beside the canal. 'I need to see it and feel it before I can really get it,' exclaimed one loudly to the dusky heavens. 'It's got to grab me or it's nowhere,' one of her companions rejoined, every bit as forthrightly, at the top of her voice. Vocal volume revealed the three to be American while their subject, disappointingly, turned out to be nothing more interesting than modern art. Modern art was the reason the four of us were in Venice, rather than to enjoy ourselves. The Americans clearly felt their subjective feelings were sufficient in them- selves to ratify what they were seeing as art. Was this the level to which art criticism had sunk at last?

All along the Grand Canal garish posters proclaimed yet another disinterring of the unengaging art of the late Andy Warhol. Amid the breathtaking architectural beau- ty of Venice one was confronted continual- ly by the bland insensibility of Warhol's images of the equally late Marilyn Monroe. A retrospective of Andy's catatonic work was currently filling the Palazzo Grassi. We were reminded at every turn that once every two years modern art becomes very big business indeed for Venice. Yet in ten years' time the Italian foreign ministry intends to take the lure of the lire into another dimension altogether by bringing World Expo 2000 to this ancient, fragile, watery city. Does such willingness to put an irreplaceable past at risk bear out the uncomfortable suspicion that quite a few Italian politicians would be perfectly happy to sell their grandmothers, if needs arose?

By contrast with the threatened Expo, the Venice Biennale brings visitors to the city at a level the existing infrastructure can just about accommodate. Hotels and res- taurants were full nevertheless and each vaporetto I took or saw was crowded. The present Biennale is the 44th. Older hands than I tell me they feel disillusioned increasingly with the realities of the recent past; both dealers and artists seem to be growing more and more cynical and venal.

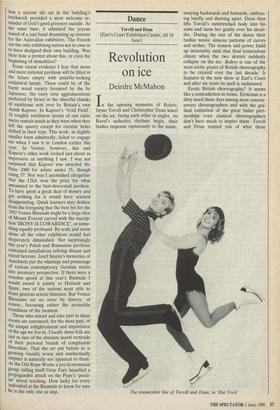

Jenny Holzer, the American artist whose fund of platitudes seems as inexhaustible as the dumb, inexplicable patience of her admirers, began advertising her candida- ture for a prize as early as Venice airport. A display board which beams her eminent- ly forgettable flashing messages has infil- trated the other boards which provide more legitimate and useful information for incoming passengers. Out in the streets, souvenir stands carry the American prophetess's message to the multitudes in the form of tawdry hats and tee-shirts. The 'It is Man', 1990, sandstone and pigment, by the British sculptor Anish Kapoor Americans are reputed to have spent well over $2 million on their pavilion for this year's occasion. Thus Ms Holzer's com- ments on life have left behind their natural habitat of the cheap Christmas cracker and have become carved, instead, in finest marble floor tiles and benches in the American pavilion. Does this make any of her homely aphorisms, such as 'IT IS MAN'S FATE TO OUTSMART HIM- SELF' or 'IT IS A GIFT TO THE WORLD NOT TO HAVE BABIES', one whit less bland or complacent? Ms Holzer's wince-inducing platitudes cover more or less the entire range of remarks one hopes one will never hear at a dinner party: `EATING TOO MUCH IS CRIMINAL', `PRIVATE PROPERTY CREATED CRIME', 'RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY'. Generally Holzer's woodshed wisdom strikes one as more confused than Confucian, nor is English grammar her strong point. Is Ms Holzer as grim and humourless as the average Amer- ican feminist or does she contemplate her world fame each day with paroxysms of hysterical disbelief? Regrettably my own thoughts on life, art, or even on Ms Holzer are unlikely to find themselves carved in rosso magnaboschi or nero marquina mar- ble floor tiles, but if they were I like to think I would have the decency to roll about on these, laughing uncontrollably. The main events of the Venice Biennale take place in the gardens which house the permanent pavilions of the 40-odd partici- pating nations and in the appropriately named Old Rope Works where the best efforts of some scores of up-and-coming artists are displayed for evaluation — if not for money. With so many exhibits to see, ample statistical evidence exists from which to adduce apparent world tenden- cies. Thus there is very little painting and less and less evidence of handmade marks in art of any kind. This was a source of real disappointment to me because the marks artists make are generally highly revealing of the character of the artist and of his or her mastery of the medium. Australia chose a brace of Aboriginal painters, Switzerland a solo minimalist, Iceland an idiosyncratic painter of myth and legend, Yugoslavia one of the most meaning-free abstract expressionists I have seen so far. The German Democratic Republic offered probably the closest thing to recognisable mainstream painting in the worthy work of Walter Libuda, whose method shared something with late Kokoschka. Probably painting accounted for only a quarter of all the work exhibited. But did this figure provide a true reflection of any new global tendency? The answer is certainly not. I suspect that most nations have worked out by now that what passes for sculpture provides an altogether safer and easier choice. Also because large sculptures fill much more of the interior spaces of nation- al pavilions it can be seen as more impos- ing. Not to put too fine a point on it, the cleverer and more artistically ambitious nations are decorating their pavilions now rather than filling them with art. In some cases artists have pierced their works into or made holes in the fabric of their national pavilions. In the case of the French paw

lion a narrow slit cut in the building's brickwork provided a most welcome re- minder of God's good greenery outside. At the same time, it admitted the joyous sound of a jazz band drumming up interest for the Australian exhibitors. The French are the only exhibiting nation not to own or to have designed their own building. Was their hole a protest about this, or even the beginning of demolition?

From recent evidence I fear that more and more national pavilions will be filled in the future simply with amiable-looking sculptural lumps. These could be of the burnt wood variety favoured by the by Japanese, the rusty iron agglomerations preferred by Israel or the cheerful chunks of sandstone sent over by Britain's own Anish Kapoor. In Kapoor's 'Void Field', 16 roughly rectilinear stones of one cubic metre remain much as they were when they left the quarry except for circular holes drilled in their tops. This work, in slightly smaller form admittedly, failed to engage me when I saw it in London earlier this year. In Venice, however, this and Kapoor's other work looked just about as Impressive as anything I saw. I was not surprised that Kapoor was awarded the Prize 2000 for artists under 35, though rising 37. Nor was I astonished altogether that the USA won the prize for what amounted to the best-decorated pavilion. To have spent a great deal of money and got nothing for it would have seemed disappointing. Quick learners may deduce from the foregoing that the best bet for the 1992 Venice Biennale might be a large slice of Mount Everest carved with the inscrip- tion 'IRONY IS COWARDICE', or some- thing equally profound. By scale and scorn alone all the other exhibitors would feel desperately diminished. Not surprisingly this year's Polish and Rumanian pavilions contained installations reliving distant and recent horrors. Jozef Szajna's memories of Auschwitz put the whinings and posturings of various contemporary German artists Into necessary perspective. If there were a wooden spoon at this year's Biennale I would award it jointly to Holland and Spain, two of the nations most able to boast glorious artistic histories. But Venice Biennales set no store by history, of course, favouring rather the invincible trendiness of the moment.

Those who attend and take part in these events are convinced, for the most part, of the unique enlightenment and importance Of the age we live in. Usually these folk are just as sure of the absolute moral rectitude of their personal brands of complacent liberalism. That the art put before us is growing visually worse and intellectually emptier is naturally not apparent to them. At the Old Rope Works a pro-homosexual group calling itself Gran Fury launched a propagandist attack on the Pope's 'pecul- iar' moral teaching. How lucky for every individual at the Biennale to know for sure he is the only one in step.

Previous page

Previous page