ARTS

Heritage

Cabinet responsibility

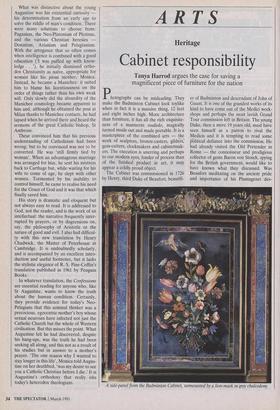

Photographs can be misleading. They make the Badminton Cabinet look toylike when in fact it is a massive thing, 12 feet and eight inches high. More architecture than furniture, it has all the rich exquisite- ness of a mannerist studiolo, magically turned inside out and made portable. It is a masterpiece of the combined arts — the work of sculptors, bronze-casters, gilders, gem-cutters, clockmakers and cabinetmak- ers. The execution is unerring and perhaps to our modern eyes, fonder of process than of the finished product in art, it may appear a coldly proud object.

The Cabinet was commissioned in 1726 by Henry, third Duke of Beaufort, beautifi-

er of Badminton and descendant of John of Gaunt. It is one of the grandest works of its kind to have come out of the Medici work- shops and perhaps the most lavish Grand Tour commission left in Britain. The young Duke, then a mere 19 years old, must have seen himself as a patron to rival the Medicis and it is tempting to read some p-Olitical defiance into the commission. He had already visited the Old Pretender in Rome — the connoisseur and prodigious collector of gems Baron von Stosch, spying for the British government, would like to have known what they discussed. Was Beaufort meditating on the ancient pride and importance of his Plantagenet des- A side-panel from the Badminton Cabinet, surmounted by a lion-mask in grey chalcedony

cent? Meeting Italy's 'King of England' and with an upstart Hanoverian dynasty just installed on the English throne he may have had romantic thoughts about his own royal ancestry. Certainly everything he did and acquired and was given in Italy had a princely quality.

These days we do not expect furniture to have an iconography, a narrative content. But the Badminton Cabinet, surmounted by the Plantagenet arms, with its majestic timepiece, its statues of the Four Seasons and its extraordinarily naturalistic details of the most ephemeral flowers and insects inlaid in pietra dura, lends itself to the kind of exegesis more usually given to that other combination of architecture and sculpture, the memorial tomb. The Cabinet touches on the big themes — Art, Nature, Time. Luckily there is an eloquent spokesman able to unlock these meanings for us: Simon Jervis, director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. He needs to do this with some urgency, otherwise the Cabinet will leave this country for America, its bizarre grandeur wrenched decisively from any kind of sensible context. And out of context it would easily look like a mas- sive bibelot.

The last major attempt to save a work of art for the nation (Canova's figure group `The Three Graces') may seem all too recent. The V & A's attempt to raise the money was unsuccessful, resulting in a mere £330,000, of which £250,000 came from the National Art Collections Fund. There could be many reasons for this the generally adverse publicity which the V & A has received, the fact that a variant of the sculpture exists in Leningrad. Perhaps there was an element of prudish- ness — the British en masse first started loving art when they discovered the early Italians. That fondness for moral probity in art has cast a long shadow. Perhaps the real problem was that no single individual at the museum could stand up and communi- cate the importance of the three marble lovelies with passion and conviction.

By an unhappy coincidence, at the same time as the 'Three Graces' appeal was get- ting under way the V & A had confidential- ly and exclusively been offered the Badminton Cabinet for £4 million by the present Duke of Beaufort. The very confi- dentiality and exclusivity of the offer meant that the director and trustees of the V & A looked at the matter without involving other British museums and galleries. They would, of course, have taken advice from the various departments in the Museum, most particularly from the department of furniture and woodwork, where Simon Jervis was then deputy keeper and acting head of department following the redun- dancy of the keeper John Morley. Jervis is unwilling to comment on the advice he gave the trustees, but given his present commitment to keeping the cabinet in Britain it seems inconceivable that he did not recommend that the trustees make urgent efforts to buy it. The V & A decided it was unable to take on the challenge. In July 1990, after two and a half centuries at Badminton, the Cabinet went to the sale- rooms and was bought by Mrs Basia Johnson, the pharmaceuticals heiress, for £8,580,000. On 18 September, on the advice of the reviewing committee on the export of works of art, an export stop was announced. On 1 October Simon Jervis became director of the Fitzwilliam Mus- eum. He was now in a position to act.

Fifteen days after taking up his appoint- ment Jervis persuaded the syndicate of the Fitzwiliiam to endorse an attempt to save the Cabinet. By 2 November Jervis had raised £750,000. By 23 November the National Heritage Memorial Fund had announced a record grant of £1,500,000 and by 14 December with £30,000 from the V & A fund Jervis had secured a quarter of the target needed to match the price paid by Mrs Johnson. On 13 February the National Art Collections Fund took the crucial decision to mount a national appeal. The importance of the NACF sup- port cannot be underestimated. It is the first major NACF national appeal since 1962 when the Leonardo cartoon was saved for the nation, and only the second in the Fund's history, Anyone of an age to be even vaguely interested in art will remem- ber that campaign. It went to the nation's heart up and down the country. Many schools still have a framed reproduction of the cartoon in earnest of their contribution.

At present Jervis and the NACF are seeking an extension of the export ban, which runs out on 17 March. Given the response so far it seems inconceivable that this should not be granted. War and eco- nomic depression may work against inter- esting the nation in what some might dismiss as a mere piece of furniture. Jervis is not downhearted, taking the Beaufort motto Nutare vel timere sperno' (I scorn change or fear') as his own and remarking that there is never a perfect time for any enterprise. He has marshalled a distin- guished array of supporters, like Sir John Plumb, the man who introduced us to 18th- century British social history. Plumb has no doubts on the matter, describing the Cabinet as 'one of the great symbols of Britain triumphant — like Blenheim Palace or Handel's music'. Now we can decide for ourselves, as the Cabinet went on display this week in the British Library wing of the British Museum. It is time to reverse the miserable statis- tics which reveal that these days only rela- tively cheap works of art are saved from export. The Fitzwilliam Museum will be an especially appropriate site for the Cabinet. It is a very grand building in its own right and contains many suitable companion works of art — Lord Fitzwilliam's great Titian and Veronese, a marvellous Grand Tour portrait of the seventh Earl of Northampton, William Beckford's gilt and lapis lazuli cup and the Duke of Marlborough's colossal statue of Glory. Whether it will go there for us all to enjoy free of charge or to Mrs Johnson's drawing room in New Jersey is for us and, more importantly, for the Government to decide.

Previous page

Previous page