Exhibitions 1

Masterpieces from the Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome (National Gallery, till 19 May)

Revelations from Rome

Martin Gayford

Writing in the 1996 Spectator pocket diary on exploring European galleries, I earnestly advised readers to visit the Galle- ria Doria Pamphilj in Rome. Little did I then know that many of its masterpieces would be on show this year at the National Gallery. Oh well, the advice remains the same — and much less of a journey is nec- essary in order to follow it.

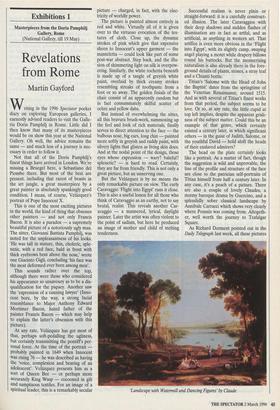

Not that all of the Doria Pamphilj's finest things have arrived in London. We're missing a Bruegel here, a Sebastiano del Piombo there. But most of the best are present, including that rarest of beasts in the art jungle, a great masterpiece by a great painter in absolutely spankingly good condition. I mean, of course, Velazquez's portrait of Pope Innocent X.

This is one of the most exciting pictures in the world, the kind of thing that obsesses other painters — and not only Francis Bacon. It is also a paradox — a supremely beautiful picture of a notoriously ugly man. The sitter, Giovanni Battista Pamphilj, was noted for the unpleasantness of his looks. `He was tall in stature, thin, choleric, sple- netic, with a red face, bald in front with thick eyebrows bent above the nose,' wrote one Giacinto Gigli, concluding 'his face was the most deformed ever born among men'.

This sounds rather over the top, although there were those who considered his appearance so unsavoury as to be a dis- qualification for the papacy. Another saw the 'expression of a cunning lawyer' (Inno- cent bore, by the way, a strong facial resemblance to Major Anthony Edward Mortimer Bacon, hated father of the painter Francis Bacon — which may help to explain the latter's obsession with this picture).

At any rate, Velazquez has got most of that, perhaps soft-pedalling the ugliness, but certainly transmitting the pontiff's per- sonal force. At the time of the portrait probably painted in 1649 when Innocent was rising 76 — he was described as having the 'voice, complexion and bearing of an adolescent'. Velazquez presents him as a sort of Queen Bee — or perhaps more accurately King Wasp — cocooned in gilt and sumptuous textiles. For an image of a spiritual leader, this is a remarkably secular picture — charged, in fact, with the elec- tricity of worldly power.

The picture is painted almost entirely in red and white. Virtually all of it is given over to the virtuoso evocation of the tex- tures of cloth. Close up, the dynamic strokes of pink which give that expensive sheen to Innocent's upper garment — the manteletta — could look like part of some post-war abstract. Step back, and the illu- sion of shimmering light on silk is overpow- ering. Similarly, the white rochetta beneath is made up of a tangle of greyish white paint, overlaid by thick creamy strokes resembling streaks of toothpaste from a foot or so away. The golden finials of the chair consist of an apparently random but in fact consummately skilful scatter of ochre and yellow dabs.

But instead of overwhelming the sitter, all this bravura brush-work, summoning up the feel and look of rich materials, finally serves to direct attention to the face — the bulbous nose, big ears, long chin — painted more softly in greyish and ruddy paint, with silvery lights that glisten as living skin does. And at the nodal point of the design, those eyes whose expression — wary? baleful? splenetic? — is hard to read. Certainly, they are far from friendly. This is not only a great picture, but an unnerving one.

But the Velazquez is by no means the only remarkable picture on view. The early Caravaggio 'Flight into Egypt' runs it close. This is also a useful lesson for all those who think of Caravaggio as an earthy, not to say brutal, realist. This reveals another Car- avaggio — a mannered, lyrical, daylight painter. Later the artist was often violent to the point of sadism, but here he produced an image of mother and child of melting tenderness. Successful realism is never plain or straight-forward: it is a carefully construct- ed illusion. The later Caravaggios with their deep shadows and sudden flashes of illumination are in fact as artful, and as artificial, as anything in western art. That artifice is even more obvious in the 'Flight into Egypt', with its slightly camp, swaying angel playing a motet while drapery billows round his buttocks. But the mesmerising naturalism is also already there in the fore- ground details of plants, stones, a stray leaf and a Chianti bottle.

Titian's 'Salome with the Head of John the Baptist' dates from the springtime of the Venetian Renaissance, around 1515. And as with several of Titian's finest works from that period, the subject seems to be love. Or so, at any rate, the little cupid at top left implies, despite the apparent grisli- ness of the subject matter. Could this be an example of that genre, which certainly existed a century later, in which significant others — in the guise of Judith, Salome, or the youthful David — hold aloft the heads of their enslaved admirers?

The head on the plate certainly looks like a portrait. As a matter of fact, though the suggestion is wild and unprovable, the line of the profile and structure of the face are close to the patrician self-portraits of Titian himself from half a century later. In any case, it's a peach of a picture. There are also a couple of lovely Claudes, a stormy baroque drama by Guercino, and a splendidly sober classical landscape by Annibale Carracci which shows very clearly where Poussin was coming from. Altogeth- er, well worth the journey to Trafalgar Square.

As Richard Dorment pointed out in the Daily Telegraph last week, all these pictures

`Landscape with Watermill and Dancing Figures' by Claude from Rome are in apple-pie order. Those interested in the difference between a painting whose delicate surface membranes are intact, and those that have been over- enthusiastically cleaned, could do no better than compare them with the National Gallery's own Velazquers, Titians and Car- avaggios and so forth from which, alas, all too often the bloom has gone.

Previous page

Previous page