TIME TO FREE MAND ELA

Richard West argues that

the South African government should take a risk

Johannesburg IF, AS seems likely, the National Party sweeps back to power in next week's general election, it should have a golden chance to settle the problem of Nelson Mandela, by finally letting him out of prison. If the opinion polls are right, President P. W. Botha will by then have dished his opponents on the political right, who think it treasonable to show any mercy to men such as Mandela. Nor has Botha much to fear at the moment from Nelson Mandela's followers in the banned African National Congress and its ally, the South African Communist Party. Between ten and twenty thousand radicals are now in detention. The boycott on schools has proved not only ineffective but deeply unpopular with most of the black scholars and still more so with parents. The cam- paign of terror by necklacing has come to a halt and most of the violence in the townships now involves faction disputes or straight tribal conflicts of Xhosa against Sotho, and, still more, Xhosa against Zulu. The leadership of the ANC in Lusaka is old and seems to have little control of its members still in South Africa. The South African secret police have infiltrated the ANC almost as thoroughly as have the Soviet secret police. The South African armed forces are stronger than they have ever been along the northern border; indeed they are probably able to take offensive action, should they wish, against Angola, Mozambique or any other country that threatens. Economic sanctions against South Africa have proved a flop. The price of gold is soaring.

For the first time in years, South Africa is in a position to free Nelson Mandela without appearing to bow under foreign pressure. Two years ago, even as late as last summer's Commonwealth Conference, the 'Free Nelson Mandela' movement was almost an international madness. The fever had spread from countries like Sweden and Britain — where streets, racehorses, uni- versity halls and even a scientific particle had been named after the famous prisoner — to take a still more virulent form in America. The blacks of Boston wanted their own separate city, named Mandela- ville. The US Congress voted for sanctions against South Africa until she abolished apartheid and freed Nelson Mandela. While the hysteria lasted, President Botha could not appear to abdicate South African sovereignty by lifting a sentence of life imprisonment. The clamour to free Man- dela had the (perhaps intended) effect of dooming him to serve his sentence. He could at any time have obtained release by promising to forswear the use of violence. He refused. But this year there is no longer a world-wide interest in Mandela. The Americans have grown bored with South Africa, a country they do not understand. Even in Britain, the cause of Nelson Mandela smacks too much of the loony Left in Brent, Lambeth and Haringey. Now that South Africa is not under press- ure to free Mandela, she has the power to do so as an act of grace.

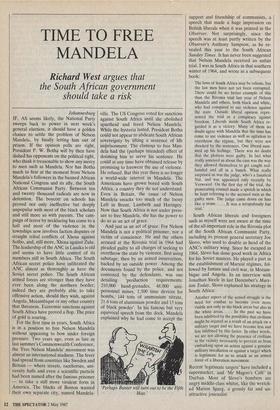

And just as an act of grace. For Nelson Mandela is not a political prisoner, nor a victim of conscience. He and the others accused at the Rivonia trial in 1964 had pleaded guilty to all charges of seeking to overthrow the state by violence, first using sabotage, then by an armed insurrection, backed by an outside power. Among the documents found by the police, and not contested by the defendants, was one detailing `production requirements: 210,000 hand-grenades, 48,000 anti- personnel mines, 1,500 time devices for bombs, 144 tons of ammonium nitrate, 21.6 tons of aluminium powder and 15 tons of black powder'. In his famous but very equivocal speech from the dock, Mandela explained why he had come to accept the `Perhaps Bunter will turn out to be the Fifth Man.' support and friendship of communists, a speech that made a huge impression on British liberals when it was printed in the Observer. Not surprisingly, since the speech was at least partly written by the Observer's Anthony Sampson, as he re- vealed this year to the South African Sunday Times. It has never been suggested that Nelson Mandela received an unfair trial. I was in South Africa in that southern winter of 1964, and wrote in a subsequent book:

The laws of South Africa may be odious, but the law men have not yet been corrupted. There could be no better example of this than the Rivonia trial last year of Nelson Mandela and others, both black and white, who had conspired to use violence against the state. Outside liberal opinion repre- sented the trial as a conspiracy against freedom. Liberals inside South Africa re- garded it as a victory. Many of them no doubt agree with Mandela that the time has come to use violence as well as agitation to overthrow the regime, but they were not shocked by the sentences. One liberal sum- med up his feelings: 'There was no doubt that the plotters were guilty. In fact what really annoyed us about the case was the way they allowed themselves to get caught red- handed and all in a bunch. What really surpriscd us was the judge, who's a fanatical Nat, and was appointed only recently by Verwoerd. On the first day of the trial, the prosecuting counsel made a speech in which he kept referring to the accused men as the guilty men. The judge came down on him like a stone. . . . It was a scrupulously fair trial.'

South African liberals and foreigners such as myself were. not aware at the time of the all-important role in the Rivonia plot of the South African Communist Party, including its present general secretary Joe Slovo, who used to double as -head of the ANC's military wing. Since he escaped in 1964, Slovo has done good work in Africa for his Soviet masters. He played a part in the establishment of Marxist regimes, fol- lowed by famine and civil war, in Mozam- bique and Angola. In an interview with Jonathan Steele in last December's Marx- ism Today, Slovo explained his strategy in South 'Africa:

Anothcr aspect of the armed struggle is the need for combat to become even more

visible not only in the black areas but also in the white areas. . . . In the past we have been inhibited by the possibility that civilians might be injured as a result of an attack on a military target and we have become less and less inhibited by this factor. In other words, we are not allowing the presence of civilians in the vicinity necessarily to prevent us from embarking upon an action against a genuine military installation or against a target which is legitimate for us to attack as an armed force of a liberation movement.

Recent 'legitimate targets' have included a supermarket, and 'Mr Magoo's Café' in Durban. Most of Slovo's bombers are angry middle-class whites, like the wretch- ed Marion Sparg, a grossly fat and un- attractive journalist. Nelson Mandela himself is credited with the plan of campaign by which the young `Comrades' established a reign of terror in some of the black townships two years ago. The 'M Plan', as it is called by the ideologues of the ANC, involved the crea- tion of cells of two or three Comrades in every block to organise and discipline the community. These 'established street structures', to borrow the sociological jar- gon loved by the ANC, governed by fear. In the eastern Cape, among Nelson Man- dela's Xhosa people, the young Comrades seized power from their tribal elders, teachers, religious ministers and naturally the police, who were the first target of violent assault. In the townships surround- ing Port Elizabeth, the Comrades suc- ceeded in closing the schools for more than a year, in boycotting white-owned shops and levying tax on any black at work. The punishment for disobedience ranged from a beating with metal rope to the necklace. Contrary to the impression given by television, the necklace is not a spon- taneous act of revenge by a lynch mob. The victim is given a trial of sorts, and told to report for execution at ten the following day. He is not kept physically under arrest but is watched by some of the Comrades. After a night of anticipation, the doomed man goes voluntarily to his fate at the chosen place in the bush. Only two in the Port Elizabeth region got away before execution. The victim is made to pay a one-rand 'burial fee' and is given a last cigarette, of dagga, like marijuana. He is given a match to light the joint, and then a second to light the tyre full of petrol around his shoulders. The psychological as well as the bodily torture involved does something to justify Winnie Mandela's boast that `with our matches and our necklaces we shall liberate this country'. The Khmer Rouge in Cambodia proved that terror can be effective in winning and holding power. Some white South Africans feel that a man who does not denounce and seems to approve atrocities such as the necklace should see out his life sentence. But this would serve the interests of the ANC and SACP, who rightly look on Mandela in jail as their main propaganda instrument. They want Mandela to live and eventually die as the best-known prisoner of the twentieth century, the object of much more sym- pathy in the West than all the millions who died and are dying still in the Gulag Archipelago. It is in the interests of Pre- toria to free Nelson Mandela and if possi- ble to debunk his pose of martyrdom.

The freeing of Nelson Mandela involves serious dangers. 'We can't really expect that he and Winnie would go for a fort- night's holiday in Kruger Park and then retire into private life,' was one rueful comment in Pretoria. At best, Mandela would go to Lusaka and then tour the world getting a hero's welcome. At worst he would go round the townships, drawing enormous crowds and causing more violent confrontation, after which he would have to go back to prison.

To free Nelson Mandela means taking a risk, but not to free him involves a greater risk: that the world will remember him as a martyr for freedom and not as a savage terrorist.

Previous page

Previous page