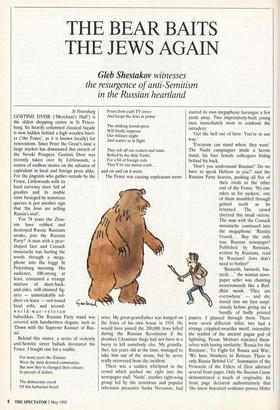

THE BEAR BAITS THE JEWS AGAIN

Gleb Shestakov witnesses

the resurgence of anti-Semitism in the Russian heartland

St Petersburg

GOSTINII DVOR (`Merchant's Hall') is the oldest shopping centre in St Peters- burg. Its heavily columned classical façade is now hidden behind a high wooden barri- er (`the Fence', as it is known locally) for renovations. Since Peter the Great's time a large market has dominated this stretch of the Nevski Prospect. Gostinii Dvor was recently taken over by Littlewoods, a source of endless stories on the advance of capitalism in local and foreign press alike. For the jingoists who gather outside by the Fence, Littlewoods with its hard currency store full of goodies and its rouble store besieged by notorious queues is just another sign that 'the Jews are selling Russia's soul'.

`For 74 years the Zion- ists have robbed and destroyed Russia. Russians awake, join the Russian Party!' A man with a pear- shaped face and Cossack moustache was hurling the words through a mega- phone into the foggy St Petersburg morning. His audience, 100-strong at least, contained a strange mixture of short-back- and-sides, stiff-chinned fig- ures — unmistakably sol- diers on leave — red-nosed local yobs, and second- world-war-veteran babushkas. The Russian Party stand was covered with handwritten slogans, such as `Down with the Supreme Knesset of Rus- sia'.

Behind this orator, a series of violently anti-Semitic street ballads decorated the Fence. I bought one for a rouble:

For many years the Zionists Were the most devoted communists But now they've changed their colours In pursuit of dollars.

The democratic creed Of this barbarian breed Pours from each TV tower And keeps the Jews in power The stinking Jewish press Will finally suppress Our military might And scatter us in flight They sell off our rockets and tanks Bribed by the dirty Yanks. For a bit of foreign cash They'll let our nation crash...

and on and on it went.

The Fence was causing unpleasant mem- ories. My great-grandfather was hanged on the fence of his own house in 1918. He would have joined the 200,000 Jews killed during the Russian Revolution if the drunken Ukrainian thugs had not been in a hurry to kill somebody else. My grandfa- ther, ten years old at the time, managed to take him out of the noose, but he never really recovered from the incident.

There was a sudden whirlpool in the crowd which pushed me right into the newspaper stall. `Nashi', another right-wing group led by the notorious and popular television presenter Sasha Nevzorov, had started its own megaphone harangue a few yards away. Two impressively-built young men immediately went to confront the intruders: `Get the hell out of here. You're in our way.'

`Everyone can stand where they want.' The Nashi campaigner made a heroic stand, his four female colleagues hiding behind his back.

returned. The crowd cheered this small victory. The man with the Cossack moustache continued into the megaphone: 'Russkiy Vestnik.. . Buy the only true Russian newspaper! Published by Russians, written by Russians, read by Russians! Jews don't need to bother!'

`Bastards, bastards, bas- tards ...' the woman news- paper seller was chanting monotonously like a Bud- dhist monk. 'They are everywhere' — and she stared into my face suspi- ciously before giving me a bundle of badly printed papers. I glanced through them. There were seven different titles; two had a

strange crippled-swastika motif, ostensibly the symbol of the ancient pagan god of lightning, Perun. Mottoes repeated them- selves with boring similarity: 'Russia for the Russians', `To Fight for Russia and Win', 'We have Nowhere to Retreat: There is only Russia Behind Us!'. Summaries of the

Protocols of the Elders of Zion adorned several front pages. Only the Russian Cause

demonstrated a touch of originality. Its front page declared authoritatively that `the latest historical evidence proves Hitler and the whole of his Politburo to have been Jewish'.

I wondered how the 'true Russian press' managed such a large print-run when even established publications have difficulties getting paper. I asked the woman if she could satisfy my curiosity on this point. She pointed at the people with the megaphone without interrupting her chant.

I took a deep breath and presented myself as a Western journalist. `Do you have a press card?' A young lad with dead blue eyes and a punk version of Hitler's fringe thrust himself at me. It seemed use- less to explain about freelancing or the lack of a business-card culture in Oxford Uni- versity. I flashed a Bodleian Library read- er's ticket at him, which did the trick. The Fringe explained that the Demo-Zionist press slanders the 'patriots' and calls them fascists. Then he studied my face more carefully.

`Are you sure you are not a Jew?' He concluded his anthopological investigation.

`You look like another Zionist spy to me.' I denied it and muttered something about Monarchist émigré organisations in Ger- many and England. That pacified Mr Fringe for a while. He explained that from Lenin (who was according to him a Rabbi's grandson) to Eltzin (patriots drop the Y, pronouncing his name to make it sound Jewish) all our rulers had been Jews, con- spiring to rob the Russian people of their statehood.

Was Brezhnev Jewish?' I enquired.

`Hal Of course, he had a Jewish wife.'

The Fringe was amused by my arrogance. 'And Stalin?'

'He wasn't a Jew,' the Cossack orator joined the conversation. 'But he killed Rus- sians as well — he can't be called a patriot.' The two of them listed the 'Jewish' West- ern leaders. Only mainland China proved to be unaffected by Zionism.

Both the Cossack and the Fringe were deputy secretaries of the Russian Party's St Petersburg section. The Fringe's name was Nikolai Bondarik (`H's a Byelorussian sur- name,' he explained apologetically). After graduating from Leningrad Technological Institute as a nuclear scientist, Nikolai started his own 'Russian business'. Thai was a 'video-salon' — a small video-cinema for showing pirated copies of Western thrillers. These 'salons' mushroomed all over Russia several years ago. There were small towns which had one barber but five video halls. Inevitably many of them col- lapsed, Nikolai's included. Nikolai held Jews responsible. Now he was a journalist and wanted to edit his own newspaper for pure Russian teenagers. The Cossack, Vladimir, was older and looked more human. He was a worker, and had spent some time in prison for an offence which he vaguely described as 'defending some- body's honour in a street-fight'. After a short spell of friendliness, caused by my interest in their biographies, both had lapsed into curt resignation. `Isn't newsprint in short supply?'

`Don't worry, we have enough.'

`How many members does the Party have?'

`More than some think.' By that time nine or ten Party members had surrounded us and were listening attentively to the con- versation. In the dispersed light of a cloudy morning their faces looked gloomy and worn. Finally I was given the Party mani- festo and told that I could study it and meet next day.

`We'll check on you meanwhile,' Nikolai smiled coldly as he wrote down my name.

I went back to my hotel. I called a jour- nalist friend, an expert on the KGB, and asked how long it would take the Russian Party to run my name through the KGB computers. He told me not to worry; the only thing they could do in a few days was to check with the airport and hotel security. 'If they have access at all,' my friend con- cluded sceptically.

I examined the manifesto. It was pre- dictable: deportation of Jews; trial of Zion- ism for the crimes of communism; a national economy where each nationality gets a share according to its size; formation of an armed militia to defend Russians from the Zionist mob.

You meet extreme anti-Semites every- where around the world. Even in England, famous for its tolerance, I ran into a well educated upper-middle-class gentleman who explained to me that the ZIL automo- bile plant in Moscow was financed by Chase Manhattan to produce arms for a Jewish takeover of the world. In England, you dismiss such people even if they pub- lish a small print-run newsletter as my acquaintance did.

In Russia, rabid anti-Semitism has a long history of institutional support. It was Peter the Great who first issued a decree forbid- ding Jews to settle in Russia. His daughter Elisabeth deported Jews en masse. Ironical-

ly, the first pogrom took place in the town named after her, Elizavetgrad. It started when a Jewish innkeeper tried to charge the drunken crowd for a broken glass jar. The slaughter went on for three days and cost 15,000 Jews their lives. After that there were pogroms in Rostov, Odessa and Kiev. The extreme right-wing groups became even more active after the revolu- tion of 1905, when Nicholas I was forced to grant a constitution (obviously a trick played on the Tsar by the Jewish lobby bent on attaining world domination). The slogan 'Crush the Kikes — Save Russia' inspired gangs of urban thugs (the notori- ous Black Hundreds) which put pogroms on an assembly-line footing.

The Black Hundreds anticipated Nation- al Socialism, yet they never had mass sup- port like the fascists in Germany and Italy: in a democratic election they would have been unlikely ever to gain a single seat. Why they had such a disproportionate influence is no mystery. Their political aims — Orthodoxy and Autocracy — coincided with those of the Crown.

As I studied the manifesto, I noticed that Russian anti-Semitism had changed slightly over the past 70 years. One of the para- graphs of the manifesto stated: 'We consid- er Christianity to be a religion of slaves, a branch of Judaism which helped to estab- lish a Zionist occupation of Russia.' Although the paragraph had been crossed out with a green felt-tip pen, one could sense that the modern anti-Semites were not too keen on Orthodoxy. Neither was there any mention of the Monarchy. The new ideals are similarly simple, however: The Union and the Army.

I dialled Nikolai's number.

`We know you are a half-breed! You don't need to call.' He hissed with rage. I hoped he was bluffing.

`Half-breed? I'm a Russian patriot, a Monarchist! What the **** is your prob- lem?'

The use of the 'honest Russian' obscenity calmed him down. 'We've checked you out.'

`And ' Nikolai lost his confidence. 'You said you were a Western journalist.'

`Yes ...'

`But you entered the country on a Soviet passport.'

They had obviously contacted airport security.

'I emigrated recently and still have a valid passport.' Nikolai was satisfied; we agreed to meet for lunch the next day.

It was two o'clock in the afternoon, but the Astoria Hotel restaurant was already full of drunks. Their faces were out of a Bruegel peasant wedding. Then my two contacts appeared. They were dressed up for the occasion — Vladimir in a Sunday- best two-piece suit, Nikolai in a colourful jumper. They seemed uncomfortable in the pretentious marble hall. The tension eased as a bottle of vodka appeared. We drank a couple of glassfuls for the future of Russia. I asked them about Christianity.

'We want to re-establish the true Russian faith, where under God we comprehend nature.' Nikolai's philosophy seemed to spring from a mixture of Nietzsche and alcohol abuse. 'Our leader Korchagin says that Orthodoxy is Zionist rubbish, but we took that out of the manifesto since a lot of our supporters are believers.' As they drank, further interesting details started to appear.

The Russian Party's constituency, Niko- lai said, was ex-KGB, ex-Party and military. He claimed it was partly funded by the army. Vladimir produced several military newspapers which had cheerful articles about the anti-Semites. They boasted that there were members of the General Staff in the Party. One of the photographs I exam- ined showed a liberal sprinkling of generals at the Party's second congress. The other source of support, they told me, was the Cossacks. The movement by Cossacks to re-establish their national identity started two years ago, but has been hijacked by former regional Communist Party leaders and turned into a rent-a-mob organisation. There were 10,000 such Cossacks in St Petersburg alone, Vladimir claimed.

As to the future plans of the Russian Party, Nikolai was outspoken. 'Most of the army supports us. They feel betrayed and just need a cause to rally round. We'll take power soon!' I almost expected Nikolai to conclude with a 'Sieg, Heil!'

Following introductions by my two Rus- sian Party contacts, I went to Moscow to meet their leader, Mr Korchagin. His head- quarters were based in a suburban cinema, lost in a labyrinth of apartment blocks and factories. There was a metal door at the back of the ticket office and a password to give, I had been told. From the outside, the grim concrete façade promised trouble: sub-machine guns, commandoes, body- searches in some windowless room. But the entry system turned out to be quite relaxed by paramilitary standards. The metal door was there all right, but the password (`Spore) was checked by a flirtatious lady who also sells the cinema tickets.

Korchagin was a clean-cut, silver-haired man, radiant with energy and health. After locking the door behind me, he went through his life story. He was a factory- worker originally, imprisoned in the Seven- ties for setting up the short-lived Russian Workers' Party, and now a publisher by profession.

We had an hour's rambling conversation in which he repeatedly explained that the Russians were a good-natured pacific peo- ple who would be killing Jews with the greatest reluctance. Korchagin was demanding Monarchist support from me in the form of Xerox copiers when the tele- phone rang. 'Yes, I'll bring him over at once,' he smartly replied, and took me to an office on the floor above to meet Sergei. I saw suddenly that Korchagin was just an employee in this enterprise, a useful idiot. Sergei introduced himself as the Party's 'economic adviser'. He turned out to be a businessman and the paymaster of these modern Black Hundreds. In true post-com- munist fashion, he immediately started fund-raising, offering to sell me a list of American pilots captured in the Korean war and executed in Siberia. I enquired 'It's amazing what a false impression one can give. Whatever made you think I was incorruptible?' whether he had any hardware for sale. After a tirade about the Communist Party Jews' stranglehold on export licences, and the need for a Monarchist-Army coalition, he ran off a whole list of goods and ser- vices, including a military transport avia- tion package and a spy satellite system. I turned down the aviation rental deal, argu- ing that IL-76s waste too much fuel. Sergei immediately offered to rent me MIG 29s complete with pilots. So was this the true function of the Russian Party: to confuse and polarise legitimate politics whilst the military high command turns a fast buck?

That may be the answer, but one should never underestimate the stupidity of the old Soviet officer class. Like the Bourbons, it has learnt nothing and forgotten nothing; as a compliant tool of the Party nomen- klatura it never developed a brain of its own. After the failure of the coup, the colonels have finally realised that their for- mer masters have sold out without splitting the cash and are now trading under a dif- ferent name. They feel robbed, and are try- ing to recoup some of their losses by selling whatever they can lay their hands on. For this epic-scale embezzlement they need a front, since they are not well-connected. But the Russian Party may represent a gen- uine possibility of power to some of the army's more foolish and fantasist elements. There is, after all, an utter spiritual vacuum in Russia; and while the nomenklatura is forced to cling to the bankrupt ideology or, more likely, to forget politics altogether, its brainless child is free to unfurl the banner of extreme nationalism. It's a long shot, but then so was the Nazi Party.

Previous page

Previous page