THE THEATRES.

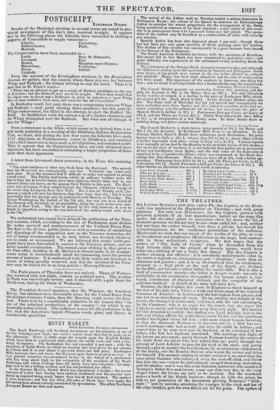

Sue LYTTON &LIVER'S new play, called The Sea Captain, or the Birth- right, was produced at the Haymarket on Thursday; and with great applause. Not only was Maensavv, the Sea Captain, greeted with prepared garlands of she best manufacture, hurled on the stage like quoits, but the other actors in succession—how far down the list of dramatis personte we did not stay to see—were called for ; and, neither last nor least, the author himself, who from a private box bowed his acknowledgments for the vociferous gratulations of the audience. Much could we wish that our report of the merits of the play, or even of its coherent and progressive effectiveness on the stage, were answer- able to these enthusiastic symptoms. We had hopes that the author of "The Lady of Lyons," when he descended from his high historic stilts to the ground of homely nature, would have achieved a striking if not a really fine drama. The Sea Captain is neither pleasing nor effective : it is essentially melodramatic—that is, the interest depends on circumstances and " situations," more than on character and passion ; and it is so ill-contrived that the excitement, strained to a high pitch at the end of the fourth act, declines in the fifth, and becomes extinct before the curtain 'falls. Nor is this a fault of construction merely—the defect is deeper seated : not only is probability in the occurrences disregarded, but human nature is out- raged, consistency of character violated, and the sympathy of the audience baulked. A sketch of the story will show how. Norman, the Sea Captain, has come to England to throw himself at the feet of his lady-love, Violet. a ward and kinswoman of the widowed Countess of Arundel: he had rescued the fair orphan from pirates, and this led to an interchange of vows. To the surprise and delight of the lovers, the stranger is courteously welcomed, and his suit encouraged, by the Countess ; who is so eager for the match, that she urges the Captain to marry and bear his bride away that very night. Her motive for this despatch is twofold : her darling son, Lord Ashdale, heir to the title and estates, affects his portionless cousin Violet, and his ambitious mother has higher views for him : a far more urgent reason, however, is, that she discovers Norman to be her own son, by a first but con- cealed marriage—she had secretly pttt away the child in infancy, and caused him to be sent over seas in boyhood, at the command of her father, who had her husband murdered. The marriage and flight of the lovers are prevented ; partly through Norman learning the secret of his birth front the priest who had reared hint up ; partly through the attempt of Lord Ashdale to pass for his rival at the altar ; and partly through a plot to murder the two brothers, by an avaricious old kinsman of the family, one Sir Maurice Beevor, who wants the estates and titles for himself. The assassin employed on this occasion is no other than the same pirate Gaussen who conveyed away the cast-off child, and threw him into the sea—where he miraculously escaped drowning, starvation, and the sharks ; and it was this same Gaussen, moreover, who murdered Norman's father five-and-twenty years ago that very day, in the very chapel where the lovers are now to be married. But the murderer makes a botch of his bloody business : though he kills the priest, he fails to get possession of the documents proving Norman's " birth- right ;" and, by mistake, attacking the younger in the cloak and hat of the elder brother, gets his OHH throat cut for his pains. Thy u,pshot of

all this " plot and counterplot" is, that the Countess acknowledges her cast-off child, after he has generously burnt the proofs of his birth- right ; and the proud Lord Ashdale embraces his newfound brother and preserver, and consents to give np the girl with a dower of half the family estates—after he finds it is of no use to object.

The absurdities of the story are apparent even in this brief outline ; but the clumsy machinery by which these marvellous coincidences are brought about, requires mote explanation to make them evident than it is worth bestowing. The improbability of the pirate and his victim meeting at so critical a moment, is comparatively unimportant ; the strange circumstance of the discarded son becoming enamoured of his mother's ward, may also be conceded to the dramatist's necessities, as well as the main incidents of the concealed birth and marriage : these, and such minor shifts as the bandying about of a bundle of papers, and the exchange of hats and cloaks, might be allowed, if the heart of the interest- were sound. The grand defect is in the character of the Countess: that a mother should put away the fruit of a first love, the child of a murdered husband, and fix her whole affection on the off- spring of a forced marriage, is unlikely enough, though possible ; but that the mother, whose conscience had never ceased to upbraid her for her cruelty, should so stifle the voice of nature as not only to avoid recognizing her child, but when he has discovered the truth, that she should peremptorily deny his claim to her affection, strengthened as it is by pity for his sufferings, and obdurately resist his prayers and entreaties for some sign of maternal tenderness, is monstrous. And for what ?- not to preserve her own good name, for that would have remained un- sullied; not from fear of a harsh husband or cruel father, for both are dead ; but merely to spare her pet darling the disagreeable necessity of giving up his prospect of usurped honours and possessions. It is a foul libel on womankind. The unnaturalness was the more shocking because superfluous ; and not less sofor the weak and even ludicrous ma- nifestation of the mother's natural feeling: the Countess naïvely asks her pet Percy, if he could forego his hereditary honours and be a pri- vate gentleman ? and on his answering that he should not relish the change at all, she exclaims- " Conic shame—come crime—conic death and doom hereafter- 11 know no son but him."

Yet in the very same scene, when Norman, incensed at his mother's calling her menials to eject him, takes his stand on the hearth and pro- claims his heinhip, her resolution fails her—not unnaturally perhaps, except for the reason she gives- " My dither's lordly mien is his! I dare not !"

Not his father's, observe, but her father's—her father, who murdered her husband and forced her to discard her first-born child This stage situa- tion told, and was greeted with a round of applause, and "one cheer more" by some enthusiastic individual in the pit : but it is only a clever clap- trap. The scene in the second act where the seaman relates his story of his peril and escape, and unconsciously -wrings the heart of the Countess, who knows him though he does not then know her for his mother—has a for stronger and deeper interest, if less effective at the moment.

Sir LYTTON Tit:farm knows the value of coups de thcaltre, and is adroit at producing them ; and we cannot but feel that in this play be has sacrificed nature and consistency to bring out more prominently his hero Norman, who swallows up all the sympathy. The Countess is a tragic character marred and out of place : her sable pall and pale face of horror haunt the stage like a perturbed spirit, which we de- voutly wish were laid to rest, for her sake and for the sake of the au- dience,. as well as the lovers'. Mrs. WARNEn's performance of this disagreeable and unthankful part is the snore deserving of praise here because she can never obtain the applause that is her due on the boards. ()n her first appearance, she realizes the striking and poetic descrip- tion— " The Dame of Arundel—bey name has terror !

Nen whiller sorcery where her dark eye falls ; ller lonely lamp outlives might's latest star ; And or her beauty some dark memory glooms, Too proud for pcnitence—too stern for sorrow."

The canker gnaws at her heart ; fear and remorse consume her blood. The effort of the -woman to stifle the voice of nature, to suppress the promptings of maternal instinct—the mother's agony of horror at her son's danger, and anguish in reflecting on the injustice she has doomed him to—the efforts of her strong will to bear down her better feelings, and the fond tenacity with which she clings to her favourite child as she recoils from the thought of dispossessing him--all these contending emotions are depicted by Mrs. WARNER with the power that the prompt:11gs of sensibility directed by skill and judgment can alone create: the character excites pain merely—unmitigated pain ; but Mrs. WARNER makes the pain intense, despite the inconsistencies she has to contend against. MACREADY, as Norman, has a part to play that carries the audience ;along with it from first to last : the bold, frank, gallant seaman, who has carved out his own way to fame and fortune—his noble nature refined by the inspiration of love—his heart yearning with filial instinct towards an unknown but not unremembered mother— finding a wife and mother at one moment, and the next having his passionate affection chilled by that cruel mother's denial of his claim— =lists all hearts in his behalf: it did not need the burning of his papers, the rivalry of his shallow younger brother, nor the attempt of the miser to murder him, to enhance the interest of such a captivating character : these tricks of melodrama indeed destroy the simplicity without height- ening the interest of the part. MAcnEAny's performance is worthy of all admiration : to say he could not miss playing it well, is as high a com- pliment as need be paid to any actor. We will not qualify this well- deserved praise by any hypercritical objections to his delivery, for it only marred one declamatory love-speech. The author, by the way, Sails to effect the intention be announces in his preface, of embodying "the early, and if I may so speak, the aboriginal sea-captain" of Eng- land in the time of RALEIGH. The costume of ELIZABETH'S reign is a Very picturesque aid to the effect of the representation ; but nothing of the spirit of that age of maritime adventure and discovery breathes in the action : the sea-captain is merged in the lover and the son. Nor do we care to have it otherwise, though the addition of individuality and nationality to the character would have made it a finer work of art. Norman, morever, talks in too Butt/wish st. strain for a seaman, ay or even a landsman of an ardent, vigorous, and earnest nature : he makes love like Claude Melnotte.

The character of Sir Maurice Beevor, a miserly dependent of the family, heir-at-law to the estates and title failing the issue of the Countess—the scoff of the household though in the confidence of the mistress—is an incongruous exaggeration of bad qualities : grasping selfish, and heartless ; thirsty for power, yet enduring insults and cois tamely of the grossest kind, from menials even ; and with the will to remove both the rightful heir and the younger brother, and taking desperate means to do it, yet failing in all his plots ; alternately fiend and buffoon,—he is a monster of deformity exciting only ridicule, not abhorrence. STRICKLAND did the best with this caricature, and looked a knightly usurer of ELIZABETH'S time : and his chuckles at the idea of being a rich lord and keeping a poor cousin to be plagued as he has been, pleased the audience mightily. Miss FAVCIT, as Violet, had only to look loving and utter soft aspira. tions and protestations ; which she does very nicely. 0. SMITH, as the pirate assassin, looks it to the life : with his swarth face, fur cap, and broad scimitar, he reminds one of those formidable executioners in onnxs's Scripture-pieces : though he can't speak, he is a living pie. ture, whose portentous aspect is eloquent. Young WEnsrEn makes the hot-blooded wayward Percy a mere empty-headed, frivolous coxcomb any thing but the " lion-hearted boy" of his cleating mother : this signal failure on his part, indeed, renders the preposterous infatuation of the Countess in preferring such an insignificant being to the noble and generous Norman still more inexplicable. Mrs. W. CLIFFORD'S part, Prudence, a waiting gentlewoman, is both ridiculous and super- fluous; but she made the best of it, as she always does. The getting-up of the piece is entitled to great praise. The dresses are superb and characteristic ; and the scenes of the Elizabethan interiors— taken without acknowledgment from JOSEPH NASH'S Old Mansions fl England—only wanted a turkey carpet over the table, and a little snore furniture, to realize the domestic state of the olden time.

Previous page

Previous page