The Letters and the Life of Francis Bacon. By James

Spedding. Vol. 6. (Longman.)—Mr. Spedding has come to a very difficult part of his work, but does not seem to lose courage. This sixth volume includes something more than two years, from July, 1616, up to the latter part of 1618. It takes in, therefore, the removal of Coke from the Chief Justiceship, the appointment of Bacon to the office of Lord Chancellor, and the execution of Raleigh. Mr. Spedding continues to give the evi- dence in the fullest manner possible; his own judgment continues to be altogether favourable to the subject of his biography. The great ques- tion of the bribes has yet to be discussed. Meanwhile, we have a shadow of the coming event in the well-known letters which Buckingham addressed to him in favour of various suitors whose affairs had come into the Court of Chancery. To these, as might be expected, Mr. Spedding attaches no weight as against Bacon's integrity. He thinks it very likely that he reproved the favourite for writing them, but that this reproof was administered by word of mouth, and that, conse- quently, no record remains of it. He does not see any "reason for sus- pecting that anything was done in [these snits] out of ordinary course." Of course he does not ; how can we try again these snits after the lapse of two centuries and a half? But is it probable that a powerful minister should go on taking the trouble of writing letters on behalf of friends if he found no benefit come of them? Was there not something more than the ordinary language of the time in the following letter to make him think that some benefit might come of them ? It is headed, "My Lord Keeper to my Lord of Buckingham, upon his being chosen Lord Keeper," and runs thus :—

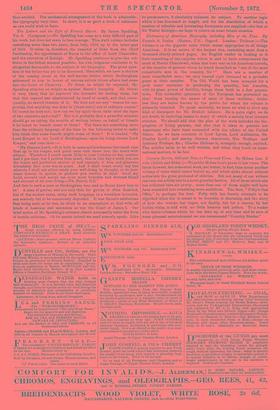

"My Dearest Lord,—It is both in cares and kindnesses that small ones float up to the tongue, and great ones sink down into the heart with silence. Therefore I coald speak little to your lordship to-day, neither had I got time, but I profess thus much, that in this day's work you are the truest and perfectest mirror of and example of firm and generous friendship that ever was in court. And I shall count every day lost wherein I shall not either study your well-doing in thought, or do your name honour in speech, or perform you service in deed. Good my Lord, account and accept me your most bounden and devoted friend and servant of all men living.—Fa. Becoti, C.S."

And this to such a man as Buckingham was, and as Bacon knew him to be ! A man of genius, and not only that, for genius is often deceived, but of the :mutest sense, using such language to a worthless favourite, can scarcely fail to be consciously degraded. It was Bacon's misfortune that being such as he was, he lived in an atmosphere so foal with all kinds of baseness and meanness as was the Court of James I. Our brief notice of Mr. Spedding's volumes almost necessarily takes the form of hostile criticism. Of its merits indeed we need scarcely speak. Like

its predecessors, it absolutely exhausts its subject. To another topic/ which it has discussed at length, and for the elucidation of which a number of valuable and interesting documents are supplied—the fate of Sir Walter Raleigh—we hope to return on some future occasion.

Previous page

Previous page