WHY I AM ASHAMED OF THE BRITISH PRESS

Simon Kelner, editor of the Independent,

on the cynicism and humbug of our newspapers

IN a recent episode of The West Wing, the television drama set in the contemporary White House, the president turns to one of his aides and says, 'Modern history? It's just television.' Given that this series is as close to an acute retelling of modern history as anything on television today. the joke is selfregarding; but the point is well made. Here, we might go even further. Modern history? It's nothing more than gossip.

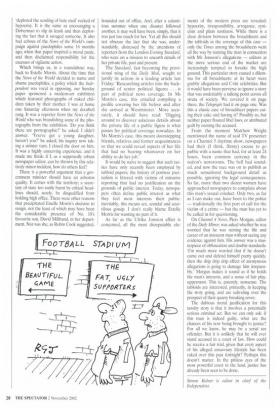

So it is that, on the word of a former TV weathergirl with a book to promote, supported by the supposedly inadvertent 'outing' by a gossip columnist, and on the lurid testimony of a collection of largely anonymous witnesses, a man is tried and convicted of serious sexual offences in the columns of our masscirculation newspapers. His career as a television presenter is, we are told in triumphant tones, in ruins. No defence, no cross-examination; the verdict from judges Yelland, Morgan and Dacre is guilty as charged.

And so it is that the Secretary of State for Education resigns, her decision portrayed by some colleagues as that of a decent woman who found press intrusions into her private life, fuelled by Westmin_—____ ster tittle-tattle. too much to bear.

There is a pungency surrounding the way some of our newspapers conduct themselves that I feel brings shame on our profession. Emboldened by the lack of effective parliamentary opposition to an all-powerful government, parts of the press see themselves, not unreasonably, as a form of unofficial counter-force. And the craven way in which the government has tailored policies (particularly in the area of home affairs) to meet the demands of Daily Mail leader-writers has served only to stiffen this self-importance. There is little evidence, however, that this ceding of power has engendered a sense of responsibility.

Take, for instance, the recent campaign that the Daily Mail has prosecuted against the Lottery Community Fund, the quango responsible for distributing the lottery funds which go to good causes. Clearly, an unelected body, through whose hands pass huge sums of money, should be held to account. And some of their decisions can properly be criticised. But it is the tone of the Mail's campaign that gives serious cause for concern. The Mail has particularly condemned the approval of grants to groups representing immigrants, minority interests and the socially disadvantaged. While I don't gainsay that this is a legitimate cause for the paper, and one that is consistent with its political agenda, there has been a spiteful, xenophobic edge to its reports that has inflamed the worst instincts of its readers.

The highly personal attacks on Diana Brittan, chair of the fund, unleashed a tide of threats and hate mail in her direction, some of which she passed on to the Independent. They contained racist abuse of the most virulent kind. One correspondent wrote: 'Dear Lady Brittan, If I had my way, you would be horsewhipped and then given five years in jail. We don't support immigrants, legal or otherwise, gays or lesbians with our donations. You are a disgrace.' Another implored Lady Brittan to 'go back to Israel ... we should have supported Hitler. We would not have you bastards on our backs giving away our money.'

Obviously, the Daily Mail cannot be held responsible for the actions of individual readers, but its subsequent statement that it

'deplored the sending of hate mailreeked of hypocrisy. It is the same as encouraging a Doberman to slip its leash and then deploring the fact that it savaged someone. It also had echoes of the News of the World's campaign against paedophiles some 16 months ago, when that paper inspired a moral panic, and then disclaimed responsibility for the excesses of vigilante action.

Which brings us, in a roundabout way, back to Estelle Morris. About the time that the News of the World decided to name and shame paedophiles, a policy which the Independent was vocal in opposing, our Sunday paper sponsored a modern-art exhibition which featured photographs of naked children taken by their mother. I was at home one Saturday afternoon when my doorbell rang. It was a reporter from the News of the World who was brandishing some of the photographs from the exhibition. 'Do you think these are pornographic?' he asked. I didn't answer. 'You've got a young daughter, haven't you?' he asked, his inquiry now taking a sinister turn. I closed the door on him. It was a highly unnerving experience, and it made me think: if I. as a supposedly robust newspaper editor, can be thrown by this relatively minor incident, how do others feel?

There is a powerful argument that a government minister should have an asbestos quality. It comes with the territory; a secretary of state too easily burnt by critical headlines should, surely, be disqualified from holding high office. There were other reasons that precipitated Estelle Morris's decision to resign, not the least of which may have been the considerable presence of No. 10's favourite son, David Miliband, in her department. Nor was she, as Robin Cook suggested,

hounded out of office. And, after a calamitous summer when one disaster followed another, it may well have been, simply, that it was just too much for her. Yet all this should not obscure the fact that she was, understandably, distressed by the attentions of reporters from the London Evening Standard, who were on a mission to unearth details of her private life, past and present.

The Standard, fast becoming the provisional wing of the Daily Mail, sought to justify its actions in a leading article last Friday: 'Researching articles into the background of senior political figures . . is part of political news coverage. In Ms Morris's case, this entailed compiling a profile covering her life before and after she arrived at Westminster.' More accurately, it should have read: 'Digging around to discover salacious details about the private life of a public figure is what passes for political coverage nowadays. In Ms Morris's case, this meant doorstepping friends, relatives and former acquaintances so that we could reveal aspects of her life that had no bearing whatsoever on her ability to do her job.'

It would be naive to suggest that such tactics have only recently been employed by tabloid papers; the history of postwar journalism is littered with victims of intrusive reporting that had no justification on the grounds of public interest. Today, newspapers often define public interest as what they feel most interests their public: inevitably, this means sex, scandal and scurrilous gossip. I don't really blame Estelle Morris for wanting no part of it.

As far as the Ulrika Jonsson affair is concerned, all the most disreputable ele ments of the modern press are revealed: hypocrisy, irresponsibility, arrogance, cynicism and plain nastiness. While there is a clear division between the broadsheets and the tabloids in the coverage of this case — only the Times among the broadsheets went all the way by naming the man in connection with Ms Jonsson's allegations — editors at the more serious end of the market are increasingly tempted to forsake the high ground. This particular story caused a dilemma for all broadsheets: at its heart were grubby allegations and C-list celebrities. But it would have been perverse to ignore a story that was undeniably a talking point across all strata of society. We covered it on page three, the Telegraph had it on page one. Was this a classic case of broadsheet papers eating their cake and having it? Possibly so, but neither paper flouted libel laws, or attributed guilt by naming the accused.

From the moment Matthew Wright mentioned the name of said TV presenter on a Channel 5 daytime show, newspapers had their (I think, flimsy) excuse to go public with a name that had, for at least 24 hours, been common currency in the nation's newsrooms. The bell had sounded, and now the race was on to publish as much sensational background detail as possible, ignoring the legal consequences. So far, more than two dozen women have approached newspapers to complain about this man's sexual conduct. Only two, as far as I can make out, have been to the police — traditionally the first port of call for the victim of a crime — but the man has yet to be called in for questioning.

On Channel 4 News, Piers Morgan, editor of the Daily Mirror, was asked whether he was worried that he was ruining the life and career of an innocent man without seeing any evidence against him. His answer was a masterpiece of obfuscation and double standards: `I'm much more worried that if he doesn't come out and defend himself pretty quickly, then the drip drip drip effect of anonymous allegations is going to damage him irreparably.' Morgan makes it sound as if he holds the man's interests, and a sense of fair play, uppermost. This is, patently, nonsense. The tabloids are interested, primarily, in keeping the story going, and are salivating over the prospect of their quarry breaking cover.

The dubious moral justification for this tawdry story is that it involves a potentially serious criminal act. But we can only ask: if this man is indeed guilty, what are the chances of his now being brought to justice? For all we know, he may be a serial sex offender. But it is unlikely that he will ever stand accused in a court of law. How could he receive a fair trial, given that every aspect of his alleged unsavoury lifestyle has been raked over this past fortnight? Perhaps this doesn't matter. In the pitiless eyes of the most powerful court in the land, justice has already been seen to be done.

Simon Kelner is editor in chief of the Independent.

Previous page

Previous page