Norwegian blue

Christopher Hudson

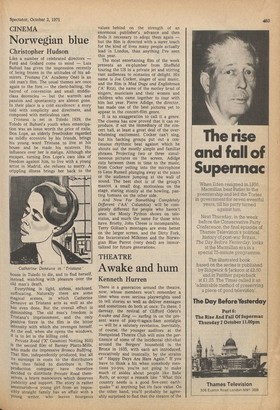

Like a number of celebrated directors — Ford and Godard come to mind — Luis Builuel has given the impression recently of being frozen in the attitudes of his admirers. Tristana ('A' Academy One) is an old man's film. The usual themes are once again to the fore — the cleric-baiting, the hatred of convention and small middleclass decencies — but the warmth and passion and spontaneity are almost gone. In their place is a cold excellence: a story told with simplicity and directness, and composed with meticulous care.

Tristana is set in Toledo 1929, the Toledo of Bufluel's youth when emancipation was an issue worth the price of exile. Don Lope, an elderly freethinker regarded as mildly eccentric by his friends, brings his young ward Tristana to live at his house and be made his mistress. His influence over her is malign. Although she escapes, turning Don Lope's own idea of freedom against him, to live with a young artist in Madrid, she refuses to marry. A crippling illness brings her back to the house in Toledo to die, and to find herself, _instead, watching with pleasure over the old man's death.

Everything is tight, airless, enclosed, suffocating. Naturally there are some magical scenes, in which Catherine Deneuve as Tristana acts as well as she has even done. But the overall effect is diminishing. The old man's freedom is Tristana's imprisonment, and the only Positive force in the film is the bitter intensity with which she revenges herself. At the end, when she opens the windows, it is to let in the killing cold.

Private Road ('X' Gaumont Notting Hill) Is the second film of Barney Platts-Mills, Who made the impressive Bronco Bullfrog. That film, independently produced, lost all its earnings in costs to the distributors Who then failed to distribute it. The production company have therefore decided to distribute Private Road themselves, a brave manoeuvre which deserves Publicity and support. The story is rather amateurish—a young girl from an impossibly straight family has an affair with a Young writer, who leaves bourgeois values behind on the strength of an enormous publisher's advance and then finds it necessary to adopt them again — but the film is directed with a surer touch for the kind of lives many people actually lead in London, than anything I've seen this year.

The most entertaining film of the week presents an ex-plumber from Sheffield touring the US in a private jet and stirring vast audiences to ecstasies of delight. His name is Joe Cocker, singer of soul music, and the film is Mad Dogs and Englishman ('A' Ritz), the name of the motley bend of singers, musicians and their women and children who came together to tour with him last year. Pierre Adidge, the director, has made one of the best pictures yet to appear in the concert-film genre.

It is no exaggeration to call it a genre. The cinema has now proved that it can reproduce, if not the immediacy of the concert hall, at least a great deal of the overwhelming excitement. Cocker can't sing, but his backing groups put out a continuous rhythmic beat against which he shouts out the mostly simple and familiar phrases. Projecting two or three simultaneous pictures on the screen, Adidge cuts between them in time to the music, from Cocker yelling into the microphone to Leon Russell plunging away at the piano or the audience jumping at the wall of sound. The best shot is of the group's mascot, a small dog, motionless on the stage, staring stonily at the howling, panting humans on the other side.

And Now For Something Completely Different ('AA' Columbia) will be completely different for people who haven't seen the Monty Python shows on television, and much the same for those who have. Briefly, John Cleese is incomparable, Terry Gilliam's montages are even better on the larger screen, and the Dirty Fork, the Incarcerated Milkmen and the Norwegian Blue Parrot (very dead) are immortalized for future generations.

Previous page

Previous page