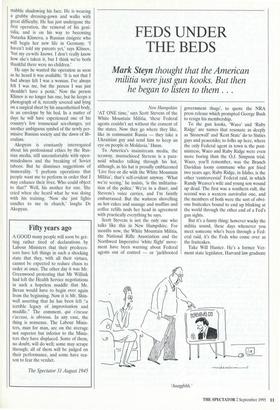

NOW YOU SEE IT, NOW YOU DON'T

Anna Blundy meets Andrei

Akopyan, Russia's leading sex-change surgeon

Moscow DR ANDREI AKOPYAN draws languidly on his cigarette and looks down at the pic- tures of naked, mutilated people laid across his glass coffee-table. There are men without penises, women with breasts that seem to be tied in knots, people with stomachs rolling down to their knees, and people with the appendages of both sexes. 'I am part surgeon, part bandit, part entrepreneur,' he explains.

Dr Akopyan is Russia's foremost sex- change surgeon and the force behind the Russian National Centre of Human Reproduction. He works under the slogan: `To love means to accept the world as it is and to wish happiness to it.' His clinic, an enclave of bright lights, sparkling floors and mood-enhancing plants deep in a Moscow suburb, also specialises in urolo- gy, endocrinology and cosmetology.

The seven doctors, 15 nurses and six administrative assistants under Akopyan's command perform 1,000 operations a year. 'We can do a seven-hour operation in three hours because I use two or three teams working on separate things simulta- neously. A surgeon has to be an adventur- er. If you don't take risks, you don't get results.'

Patients at the clinic are means-tested and charged accordingly. Usually the cos- metic surgery like breast 'correction', rhinoplasty and abdominoplasty is the most expensive. He claims to do most of his sex-changes free of charge out of sheer pity. 'Of course, the cosmetic surgery and stuff are just silly, completely unnecessary, I know, but it pays for the important oper- ations,' he says. The important operations are the innovative and highly successful methods of treating infertility. He also fits prosthetic testicles and penises.

While many might think the cases of necessity for a prosthetic penis would be rare, Akopyan insists that the 'severing of the member' is reasonably common. 'We had two blokes in from Ryazan a while ago,' he says, brandishing the appalling 'before', 'during' and 'after' photographs. 'They had got into a row with someone and when they finally passed out from the vodka he cut their penises off. They didn't come in for 20 days, so it was a tricky job. Look, those are the testicles,' he said, pointing at something round in the bloody mess of the 'during' picture. 'Oh, no, maybe they're not. They look a bit like them, though.'

Dr Akopyan does not immediately inspire a person with the confidence to entrust him with his (or her) genitalia. Only 36, he came late to medicine, though both parents are doctors. 'I was kind of a hooligan in my youth,' he says. 'They tried to lock me up a couple of times for this and that.' His lack- adaisical manner and strange philosophising (`You can't train to be a psychologist. We are all psychologists in this world'), coupled with the large leather whip on the wall of his mirrored mini-gym and his two-person gold-and-white Jacuzzi, conspire to make him a slightly sinister figure. The palatial flat was designed and built by his titanic tat- tooed bodyguard, Sasha.

Despite his protestations to the con- trary, Dr Akopyan is famous mostly for his sex-changes, an undeniably new departure for Russian medicine. On the way to his clinic, his tinted-windowed Mercedes is stopped by armed police. Akopyan oozes out of the passenger seat and smiles con- descendingly at the young men. 'I am Dr Akopyan,' he announces soothingly, prof- fering his visiting card. One of them peers at it suspiciously and then laughs in embar- rassment. 'Oh, sorry,' he mutters, and waves us on.

Akopyan loves to shock. He revels in screening videos of television interviews showing women he has created wearing very short skirts and talking about their inner selves to a background of strip-club music. The gleefully presented photographs of their operations in progress are frighten- ing and grotesque. Even the dextrous sur- geon grimaces at the pictures of a young woman having a penis made from a chunk of her stomach. 'I prefer to make men into women, although it is the more complicat- ed operation. The other way round is dis- tasteful — if you've got it, why spoil it?'

Dr Akopyan's office at the clinic is deco- rated with garish pastel drawings of hour- glass nudes in suggestive poses, and his desk is adorned with variously sized breast implants and prosthetic testicles. It is here that he runs a campaign to rid the health- care system of the stifling bureaucracy of the Soviet era. Although his clinic is an arm of the Ministry of Health, since he took over three years ago he has tried to dis- pense with all the time- and money-wasting referrals and re-referrals of the old system. His clinic used to be a 500-bed hospital serving its surrounding area, and, though he currently occupies only the fifth floor, where doctors flit about in magnesium white coats and besuited guards hover at the door, he is trying to expand into the rest of the complex.

Akopyan is respected in both Russia and the West. At home he is revered largely for his fantastic financial success, which has provided him with his opulent nouveau riche flat and the opportunity to ensure preferential treatment at the local Geor- gian restaurant, Mama Zoya's, by paying double. His cosmetic surgery has amazed Russians, who had previously assumed that American film stars just didn't get old, and earned him headlines like 'Rejuvenation is now possible'.

The concept of artificial beauty is new to Russia and people are clamouring, accord- ing to Akopyan, for the perfect breast. Abroad, he is known for his ground-break- ing techniques. His use of foetal tissues in sterility treatment has gained the highest success rate in Europe, apparently. He says he offers the cheapest and most effective treatment in Europe too, but none the less most of his patients are from the former Soviet Union. The sex-changes are under- taken by people who are mostly from the big cities, says Akopyan, 'misfits who live in railway stations, who have never integrated because they couldn't have the sex-change'.

Nikolai Klimov is one person who says he will be eternally grateful to the doctors at the Centre of Human Reproduction. He sits smoking, huddled in a tiny room off the main corridor of the clinic, a few days of stubble shadowing his face. He is wearing a grubby dressing-gown and walks with great difficulty. He has just undergone the first operation, the removal of his geni- talia, and is on his way to becoming Natasha Klimova, a Russian emigree who will begin her new life in Germany. 'I haven't told my parents yet,' says Klimov, 'but my ex-wife knows. I don't really know how she's taken it, but I think we're both thankful there were no children.'

He says he wanted the operation as soon as he heard it was available. 'It is not that I had always felt I was a woman. I've always felt I was me, but the person I was just shouldn't have a penis.' Now the person Klimov is no longer has one, but he keeps a photograph of it, recently severed and lying on a surgical sheet by his anaesthetised body, in an envelope by his bed. In a matter of days he will have experienced one of his country's few transsexual sex-changes, yet another ambiguous symbol of the newly per- missive Russian society and the dawn of lib- eralism.

Akopyan is constantly interrogated about his professional ethics by the Rus- sian media, still uncomfortable with open- mindedness and the breaking of Soviet taboos. But he dismisses suggestions of immorality. 'I perform operations that people want me to perform in order that I may enhance their lives. Who could object to that?' Well, his mother for one. She cried when she heard what he was doing with his training. 'Now she just lights candles to me in church,' laughs Dr Akopyan.

Previous page

Previous page