ARABIAN SURREY

Nicholas Glass on a meeting in Purley between

Sir Wilfred Thesiger and two tribesmen who accompanied him into the Empty Quarter

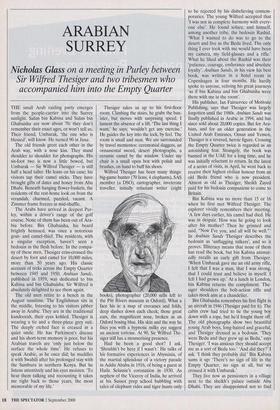

THE small Arab raiding party emerges from the people-carrier into the Surrey sunlight. Salim bin Kabina and Salim bin Ghabaisha are now about 70; they don't remember their exact ages, or won't tell us. Their friend, Umbarak, 'the one who is blessed', will know. He turned 90 in June.

The old friends greet each other in the Arab way, with a nose kiss. They stand shoulder to shoulder for photographs. His six-foot two is now a little bowed, but Umbarak — Sir Wilfred Thesiger — is still half a head taller. He leans on his cane; his visitors tap their camel sticks. They have brought gifts of dates and honey from Abu Dhabi. Beneath hanging flower-baskets, the residents of the rest-home look on from the verandah, charmed, puzzled, vacant. A Zimmer frame freezes in mid-shuffle.

The Arabs have arrived in deepest Pur- ley, within a driver's range of the golf course. None of them has been out of Ara- bia before. Bin Ghabaisha, his beard brightly hennaed, was once a notorious goat- and camel-thief. The residents, with a singular exception, haven't seen a bedouin in the flesh before. In the compa- ny of these men, Thesiger criss-crossed the desert by foot and camel for 10,000 miles, more than 50 years ago. His classic account of treks across the Empty Quarter between 1945 and 1950, Arabian Sands, published in 1959, was dedicated to bin Kabina and bin Ghabaisha. Sir Wilfred is absolutely delighted to see them again.

The old men retire to a bench in the August sunshine. The Englishman sits in the middle, listening to his visitors jabber away in Arabic. They are in the traditional kandoorah, their eyes kohled. Thesiger is wearing a tie and a three-piece grey suit. The deeply etched face is creased in a quiet smile. He has Parkinson's disease and his short-term memory is poor, but his Arabian travels are 'only just below the surface the whole time'. He refuses to speak Arabic, as he once did; he muddles it with Swahili after his prolonged stay with the Samburu in northern Kenya. But he listens attentively and his eyes moisten. `To hear them talking and recounting it takes me right back to those years, the most memorable of my life.' Thesiger takes us up to his first-floor room. Climbing the stairs, he grabs the ban- ister, but moves with surprising speed. I lament the absence of a lift. 'The last thing I want,' he says; 'wouldn't get any exercise.' He guides the key into the lock, by feel. The room is small and neat. We are surrounded by travel mementos: ceremonial daggers, an ornamental sword, desert photographs, a ceramic camel by the window. Under my chair is a small open box with polish and brushes, on hand to buff his shoes.

Wilfred Thesiger has been many things: big-game hunter (70 lions, 4 elephants), SAS member (a DSO), cartographer, inveterate traveller, initially reluctant writer (eight books), photographer (20,000 stills left to the Pitt Rivers museum in Oxford). What a face his is: a map of crevasses and folds, deep slashes down each cheek; those great ears, the magnificent nose, broken as an Oxford boxing blue. His skin and the way he fixes you with a hypnotic milky eye suggest an ancient tortoise. At 90, Sir Wilfred The- siger still has a mesmerising presence.

Had he been a good shot? I ask. `Shouldn't be here if I wasn't.' He talks of his formative experiences in Abyssinia, of the martial splendour of a victory parade in Addis Ababa in 1916, of being a guest at Haile Selassie's coronation in 1930. As nephew of the Viceroy of India, he arrived at his Sussex prep school bubbling with tales of elephant rides and tiger hunts only to be rejected by his disbelieving contem- poraries. The young Wilfred accepted that `I was not in complete harmony with every- one else'. He found solace, and himself, among another tribe, the bedouin Rashid. `What I wanted to do was to go to the desert and live as the Bedu lived. The only thing I ever took with me would have been my camera, my field-glasses and a rifle.' What he liked about the Rashid was their `patience, courage, endurance and absolute loyalty', Arabian Sands, in his view his best book, was written in a hotel room in Copenhagen in four months. He hardly spoke to anyone, reliving his great journeys `as if bin Kabina and bin Ghabaisha were there with me in the room'.

His publisher, Ian Fairservice of Motivate Publishing, says that Thesiger was largely forgotten until the 1980s. Arabian Sands was finally published in Arabic in 1994, and has since sold about 20,000 copies. But for Ara- bists, and for an older generation in the United Arab Emirates, Oman and Yemen, Thesiger is a revered, heroic figure. Crossing the Empty Quarter twice is regarded as an astonishing feat. Strangely, the book was banned in the UAE for a long time, and he was initially reluctant to return. In the latest of a series of visits, in April, he went back to receive their highest civilian honour from an old Bedu friend who is now president. Almost as old as Thesiger, Sheikh Zayed paid for his bedouin companions to come to Britain.

Bin Kabina was no more than 15 or 16 when he first met Wilfred Thesiger. The explorer vividly remembers their meeting. `A few days earlier, his camel had died. He was in despair. How was he going to look after his mother? Then he grinned and said, "Now I've you, and all will be well."' In Arabian Sands Thesiger describes the bedouin as 'unflagging talkers', and so it proves. Illiteracy means that none of them has read the book, but bin Kabina animat- edly recalls an early gift from Thesiger. `When Umbarak gave me an old army rifle, I felt that I was a man, that I was strong, that I could trust and believe in myself. I felt I had grown up.' At a lunch in London, bin Kabina returns the compliment. The- siger shoulders the bolt-action rifle and takes mock aim at a chandelier.

Bin Ghabaisha remembers his first flight in an aircraft in 1946 (Thesiger paid for it). The cabin crew had tried to tie the young boy down with a rope, but he'd fought them off. The old photographs show two beautiful young Arab boys, long-haired and graceful, and Thesiger dressed as a bedouin. 'They were Bedu and they grew up as Bedu,' says Thesiger. 'I was anxious they should accept me as a sort of Bedu too.' And did they?' I ask. think they probably did.' Bin Kabina sums it up: 'There's no sign of life in the Empty Quarter, no sign at all, but we crossed it with Umbarak.'

They live now as pensioners in a village next to the sheikh's palace outside Abu Dhabi. They are disappointed not to find Thesiger living in a castle. As companions in his Arabian adventures, they privately hope for medals and tea with the Queen Mother. They are briefly mollified. The Queen's cousin Patrick Lichfield is to be a guest at a lunch at the Naval and Military Club. But at the last minute he cancels. At the end of our interview, I tentatively asked Sir Wilfred if he might read for us from Arabian Sands. 'No,' he says, 'I've never read out loud. It would be too like being at prep school,' and he smiles.

Nicholas Glass is Arts Correspondent for Channel 4 News.

Previous page

Previous page