The queer case of the missing evidence

Byron Rogers

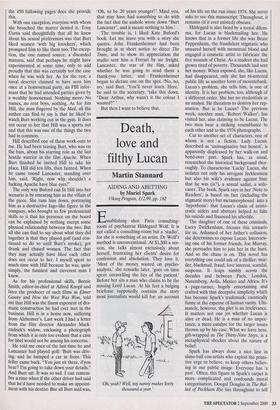

BURT LANCASTER by Kate Buford Aurum, £19.99, pp.456 Biography is a cosy enough activity. It allows someone to sit in judgment and have none of his pronouncements queried by readers who never knew the deceased. What changes everything is when they did. Kate Buford's biography of the film star Burt Lancaster is the first time this had happened to me.

Earlier this year the Daily Mail in a two- page feature spread declared that Lancast- er, a father of five, had been homosexual. It went on to say his business partner, James Hill, was a gay man who had pro- cured men for him. This came as a bit of a shock, for I have spent much of the last 25 years in Hill's company, and in London and Los Angeles got to know him as well as I do any human being. He stayed with my family, I stayed with him and his, meet- ing his ex-wife and friends, including Burt. Odd that they and Jim should have forgot- ten to mention that he was a poof.

What was almost as odd was that a month after the Mail feature, Vanity Fair, in an even longer article on the two and their film company, also forgot to mention this. Instead it carried an eye-witness account of a board meeting at Hecht Hill and Lancaster, in which these lunatics seri- ously discussed a new post of company pro- curer, only this time of women. The company, according to the screen-writer Ernie Lehman, was already 'rife with wom- anising', but until that point, apparently, supply had been part of Burt's corporate duties, procuring women for Hill, 'and not just any women — movie stars'. He must have had the edge on his partner in this, for Hill ended up married to Rita Hay- worth.

So if Lancaster, the closet homosexual, was procuring women for Hill, and Hill, the closet heterosexual, was procuring men for Lancaster, what was their company up to? Hecht Hill and Lancaster, the first inde- pendent to break the grip of the studios, was at that point the most successful film company in the world, having made in quick succession Marty (which won four Oscars), Trapeze and The Sweet Smell of Success, and was thinking of taking over MGM. How did they manage to fit this in, given all that procuring?

It is a question the two journalists forgot to ask. But then they also forgot to men- tion Kate Buford's new biography of Lan- caster, on which they appear to have based, in the Mail's case most, of their material. There has been a whole lot of forgetting going on.

Miss Buford's book is not the usual scissors-and-paste biography of a film star. She has done her research and met the people in the foreground, so it is probably as close to a definitive biography as we shall get. It is readable, funny, and infor- mative on the films; it is just that when it comes to the man this is a very rum book indeed.

Now you can argue that this does not matter in a biography of a man who spent his working life being other men. Who cares what Lancaster was like in private when such images survive as of him rolling in the surf with Deborah Kerr in From Here to Eternity? 'English dame,' Hill said to me once. 'I remember him coming into the office to tell me they were in love. I told him not to be silly. I mean, she had kids, and old Burt, he had a whole house full of them. Amazing people, actors. Ten days later he had forgotten her name, and soon all he could remember was the way the water got up his ass.'

But where it does matter is what it tells you about the biographer. Take Lancaster's sexuality, the rumours about which contin- ue to intrigue many people, for this was the most masculine and athletic of all the stars, a man who, as William Goldman wrote, `exuded physical menace'. Kate Buford promises much. On page six she announces, 'There is compelling evidence that he was bisexual,' but then nowhere in the 450 following pages does she provide this.

With one exception, everyone with whom she broached the matter denied it. Tony Curtis said thoughtfully that all he knew about his sexual preferences was that Burt liked women 'with big knockers', which prompted him to like them too. The excep- tion, the one named source, a discarded mistress, said that perhaps he might have experimented at some time, only to add proudly that this was certainly not the case when he was with her. As for the rest, a naval deserter claimed to have seen him once at a homosexual party, an FBI infor- mant that he had attended parties given by a wealthy homosexual. Nothing more. No names, no rent boys, nothing. As for Jim Hill, the man fingered by the Mail, all the author can find to say is that he liked to watch Burt working out in the gym. It does not occur to her that Hill was a sports nut and that this was one of the things the two had in common.

Hill described one of these work-outs to me. He had been teasing Burt, who was on the bars, about his starring role as the last hostile warrior in the film Apache. When Burt finished he invited Hill to take his place. Hill did ten lifts, then fainted. When he came round Lancaster, standing over him, said, 'Right, now why shouldn't a fucking Apache have blue eyes?'

The only way Buford can fit Hill into her scenario is by smearing him as the villain of the piece. She runs him down, portraying him as a destructive Iago-like figure in the company, who brought so few professional skills to it that his presence on the board can be explained by nothing except some physical relationship between the two. But all she can find to say about what they did together is that they played golf (and con- tinued to do so until Burt's stroke), got drunk and chased women. The fact that they may actually have liked each other does not occur to her. I myself spent so much time with Hill because he was, quite simply, the funniest and cleverest man I knew.

As for his professional skills, Bernie Smith, editor-in-chief at Alfred Knopf and later the producer of such films as Elmer Gantry and How the West Was Won, told me that Hill was the finest exponent of dra- matic construction he had ever met in the business. Hill is in a home now, suffering from Alzheimer's. Last week I had a letter from the film director Alexander Mack- endrick's widow, enclosing a photograph from which it is only too evident that a case for libel would not be among his concerns.

He told me once of the last time he and Lancaster had played golf: 'Burt was driv- ing; and he bumped a car in front. This feller came back. "You just sit there, d'you hear? I'm going to take down your details." And Burt sat. It was so sad. I can remem- ber a time when if the other driver had said that he'd have needed to make an appoint- ment with his dentist. But all Burt said was, `Oh, to be 20 years younger!" Mind you, that may have had something to do with the fact that the asshole wrote down "Burt Lancaster", and it meant nothing to him.'

The trouble is, I liked Kate Buford's book. Let me leave you with a story she quotes. John Frankenheimer had been brought in at short notice to direct The Train, and to show its appreciation the studio sent him a Ferrari by air freight. Lancaster, the star of the film, asked whether he was going to send them a thank-you letter, and Frankenheimer began to dictate one on the spot. 'No, no, no,' said Burt. 'You'll never learn. Here,' he said to the secretary, 'take this down. "Dear Arthur, why wasn't it the colour I wanted?" ' But then I want to believe that.

Previous page

Previous page