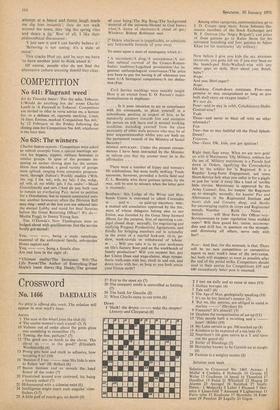

Auberon Waugh on new novels

Head to Toe Joe Orton (Blond 35s) In a very good week indeed for novels—we will be raurning to this week's crop through- out the thin days of February and early March—Joe Orton's novel was chosen first because it excited the greatest expectations. Those who remember Entertaining Mr Sloane and Loot will know that Orton had a pleasant wit and a pretty taste for paradox. Add, to this the natural sympathy we all feel for a writer who has had the misfortune to be murdered in particularly gruesome cir- cumstances, and I should have thought that Blond was on to a winner. But readers will find that the book puts severe demands on their powers of concentration.

The story is a fantasy about Gombold who falls off the earth ittto Atlas's hair and spends the rest of the novel wandering about the giant's body with various friends whom he picks up on the way. He is thrown into pri- son, escapes on a fish, is carried by an eagle, joins a war, comes to a land where the women are in control, another where every- body keeps changing sex (transexualism. is a strong theme throughout), another where people have the heads of dogs etc, etc. It ends when the giant dies. Is this symbolic of doomwatch, pollution, nuclear contamina- tion? There is nothing in the text to suggest so, and by the time one reaches the end, one has rather ceased to care. Clearly, Mr Orton's intention was to give us a modern Gulliver. Lacking Dean Swift's concentration of pur- pose, he started introducing irrelevant jokes, some quite charming. some marred by that heavy facetiousness which one sees in the new, unreadable Tit lies, and is plainly 'what passes for humour among humourless people : `I could recite the whole of Shox- bear, Arrispittle, Grubber. Taciturn. Saint Trimmer-Ac-Whinous. Saint Ginn of the Crutch. Goitre, Dirty and Kneetchur.'

We are left with something which is a cross between Alice's Adventures in Wonder- land and Sinhad the Sailor, both admirable books in themselves, but miscegeniferous as bedfellows. The weakness of fantasy, as I never tire of pointing out in these pages, is that it must be rigidly controlled as to form. or the reader's attention will wander. There must, somewhere, be a logic behind it all, however invented. Carroll realised that, so did Swift but not Orton.

Scarcely a reader, I guess. will be able to finish the book at a single sitting without his attention wandering, even if he does not end up singing of Mount Abora. The pub- lisher describes it as a tour de force, which is exactly what it isn't. One ends with a dis- tinct feeling that one has not, on this occa- sion, fed on honeydew or drunk the milk of paradise. There are some excellent vignettes in it—worthy of Orton, worthy of Swift— one on literary criticism, one on gossip column writing, another on, war: 'No one knew why the war was being fought, though several imagined it was to prevent the enemy raping their wives, and others said it was to preserve free speech . . . The left buttocks were a dreary lot. They talked of duty a good deal. They also said they had the tide of history on their side. There were no brothels, which depressed Squall . . . the right buttocks, they had heard, were a better mob.

"Squall says the tide of history is on the right buttocks' side, and we ought to be over there with them."

'So they deserted to the enemy.'

Mr Orton's book also has the quality, which I have remarked in others, that one

can open it anywhere and read ott without feeling in any way deprived by ignorance of what has gone before. It would make a very

good book to leave in the lavatory, beside old copies of Punch, Lord Halifax's Ghost Book etc. But, before leaving Mr Orton, I should like to make a serious point. We are told that he wrote this book while working in a chocolate factory by night and working feverishly in the day. I do not doubt for a moment that many of the book's defects arise from this—its scrappiness, its lack of narra-

tive precision, its unevenness of quality. Or- ton was an extremely talented writer, who could certainly have written a much better book in other circumstances. There is scarcely 'a-male writer in England who does not have his own equivalent of Orton's chocolate fac- tory; and creative writing suffers gravely as a result. If our public librarians, who draw a comfortable salary living off the sweat of other people's creative effort, are too repul- sively idle to prepare lists of books bor- rowed, why cannot we simply have authors' begging boxes in every public library? En- velopes would be provided, in which any-

body who had enjoyed a book might put a penny. threepence, even a shilling if he felt

inclined, writing the name of the book and the author on the outside. These boxes could then he sent to the Society of Authors or some such to organise the shareout.

J. Spencer Grendahl's first novel is not one which I should recommend being left in the lavatory. The first half is extremely funny for anybody who is able or willing to grasp the central joke of opting out. This joke is the one great boom area of postwar humor- ous writing. Catch-22 is a good example— and drugs give it a new extension. But pot- writers must avoid self-indulgent descent into the cliches of inarticulate violence. This is not so much because they are wrong to feel inarticulately violent but because it makes dull reading. The essence of writing is corn- munication and those who are unwilling or unable to communicate should try some other way of earning their bread.

Mr Grendahl's hero, Eric, is converted from liberalism to what he describes as radi- calism when, as a vso teacher in Northern Nigeria, he witnesses the massacre of the lbos there in 1966. Leaving Nigeria he settles with his appalling wife (excellently sketched) in Tangier and becomes depressed by events in Nigeria as Mr Stewart's boys move in to finish the job of putting the lbos in their place. Some weeks ago I criticised a writer for using the emotive powers of Auschwitz and Hiroshima too glibly. The poor Biafrans

are put to very good use 'here in a story which involves the murder of a Jewish girl

by Arabs to point the old-fashioned liberal (one almost dares suggest Christian) moral that one should not maltreat people for ethnic reasons.

The second half is more intensely erotic and less funny. 1-always reckon that one or

at• most two vivid descriptions of sexual

activity is enough for any novel—people can always go back to them, after all—but Mr Grendahl gives us six. The main point about the book is not the sermonette on race rela- tions—although I am delighted to see Mr Stewart's crime gain currency as art inter- national swear word—but in the language and life-style of American hippies in Tan- gier. On meeting someone: 'his fuzzy attempt at a beard and funny laugh made

me dig him instantly': they do not walk around the town, they 'dig the spring rites and dance a jig.' Best of all, I like their philosophical discussions;

'I just saw it and I can hardly believe it.' `Believing is not seeing; it's a state of mind.'

This cracks Hud up, and he says we have `to have another joint to think about it.'

Of course, people who do not find the alternative culture amusing should stay clear.

Previous page

Previous page