Teng's task

David Bonavia

Hong Kong The political wheel has come full circle in Peking, and even shows signs of' taking a good quarter-turn further.

Broadcasts from the mainland suggest that the eleventh congress of the Chinese Communist Party may already have been convened to formalise the full rehabilitation of Teng Hsiao-Ping, and the purge of Mao's former associates. The official news from Peking is simply that the congress will be convened `at an appropriate time this year'. .Certainly it .would make sense to hold it immediately after the already announced third plenum of the Tenth Central Cornmittee, rather than sending all the delegates home and then bringing them back to Peking in a few weeks.

Whether the congress is convened now or later is less important than the obvious substance of the decisions it is to endorse. The rehabilitation of the seventy-four-year-old Teng as vice-premier, vice-chairman of the Party and chief of staff means that he will be given full rein to implement the policies Which brought about his temporary downfall last year because he tried to push them too fast.

Teng's policies were summarised in three reports which he drafted about two years age, concerning economics, party organisation, modernisation of the army, scientific research and industrial organisation. This time last year he was, being bitterly attacked by name in the national media for these reports, which basically call for what Westerners style a more `pragmatic'

approach to China's developmental problems.

Now the media are attacking the attackers. Leading figures in the party, the army and the propaganda apparatus have been Purged for having taken part in the antiTeng witch-hunt of 1976. Teng is back, grinning warily in the official photographs Ny.hich rank him beside Mao's successor, ipirtY-four-year-old Chairman Hua Kuo eng, and his most important champion, s„eventy-eight-year-old Marshal Yell "-hien-Ying, the defence minister. To all 4ePPeara0ce5, China has a troika gov

rnment pending the announcement of the nevi, Politburo.

NOW that the Chinese themselves have °finitely disposed of the fallacy that their Polities were never divided between `rad

ical' and 'moderate' factions, it is important to consider just what the victorious `moderate' line – as incorporated in Teng – will mean for internal policy.

China cannot have its cake and eat it – indeed there is precious little cake to go around, and jusfenough.bread. The country is not desperately poor, but it is poor enough, and the current population growth of perhaps twenty million mouths a year indicates that this year's purchases of some seven million tons of grain will continue to be a burden on the exchange reserves.

Teng is a moderniser who believes that the peasarsts, given reasonable incentives, will look after themselves fairly well. The entire thrust of his economic thinking is towards industrialisation and technology. This may seem progressive to the Westerner or the admirer of the Japanese pattern, but it begs some important questions about Chinese development.

The Chinese have a strong racial pride, but are still somewhat lacking in a sense of national cohesion – hardly surprising in a divided nation which has traditionally learned to revere the family, the clan and the ancestors more than the ruler., This clannishness, which amounts to an absence of public spirit little comprehended by the admirers of package-tour China, is a particularly serious problem among the peasants who make up four-fifths of the population.

The conservatism of the peasantry actually defeated Mao, who is often seen as a leader remarkable for his success among peasants. The last two decades of his life were spent in coming to terms with the fact that the peasantry would do nothing in which it saw no early benefit for itself. Tent is less interested in Changing the basic attitudes of the peasants, evidently believing that sheer necessity will force them to keep up with the advanced pace of industrialisation which he seeks.

But in taking this attitude he may be calling down on his head the ills which countless Third World leaders have brought on themselves by trying to industrialise quickly before the country's social fabric was ready. Nobody can blame him for the attempt, but there was a core of penetrating thought in Mao's analysis of China which suggests that the attempt may be no more successful in the end than it has been in India, Indonesia or Latin America. Peasant poverty remains a serious problem even in the Soviet Union, and for that matter the Mediterranean. Can Teng's China beat it?

Teng seems convinced that an economy led by technology, industry and foreign

trade can put the ring through the peasantry's nose. And Mao's alternative was hardly attractive – turning the urban youth into peasants simply because there were not enough jobs for them in the cities.

I spoke recently to a young Chinese man who fled to Hong 'Kong from a commune in

Kwangtung province a few years ago., as a

disillusioned,-'Down to the Countryside'Red Guard. He said the peasants never wel comed the young people from the cities, because they were simply a drain on the available food supplies. And most of the urban youths were simply itching for a chance to get back to the cities, primitive though they are by the standards of the developed world: Can Teng create such a buoyant socialist economy that the urban industries can absorb not only the school-leavers coming on the job market, but also provide jobs for enterprising young people who see no

future for .themselves on the communes? That is what modernisation in China must mean, and it' Teng cannot pull it off, it is doubtful whether anyone can.

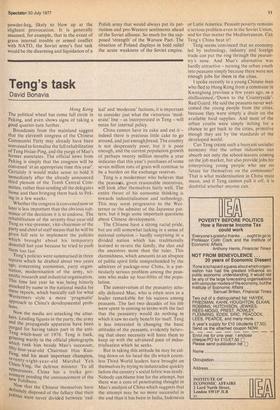

Previous page

Previous page