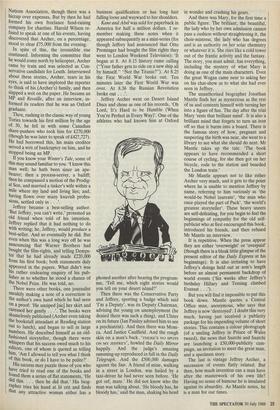

His own finest invention

Byron Rogers

IN-FOR-A-PENNY: THE UNAUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY OF JEFFREY ARCHER by Jonathan Mantle

Hamish Hamilton, £11.95, pp.264

The American senator Daniel Moyni- han had this to say the other night on television: 'There's been a kind of leakage of reality in this decade, a sense that reality is an illusion that can be overcome, a sense that what you say is real, and that if you say pleasant things, then the reality is pleasant.' And, he might have gone on, if you say them often enough and loudly enough no one will ever contradict you. Mr Jeffrey Archer has founded his career on this.

First, the leakages. Newspaper articles have variously described his late father as the British Consul in Singapore, an officer in the Royal Engineers, the colonel of the Somerset Light Infantry. Mr William Archer, who died when his only child was 13, was a semi-invalid who worked in local journalism.

Jeffrey Archer, then 20, who had been briefly in the army and a policeman in Brixton, applied for, and got, the job of gym master at Dover College, a boarding school. The book cites his c.v. which claims he had done an instructor's course at Sand- hurst and had taken an honours diploma from Berkeley, but also informs us that he had been to neither. He got himself accepted into the post-graduate education course at Oxford, though he apparently had no degree and no A-levels. When he managed to stay on at Oxford, and became President of the Athletics Club, Cam- bridge queried the position of a man who was not an undergraduate, a graduate or a post-graduate. They claimed, with some justification, that he must therefore be a professional, but the matter drifted away, as such things often do in English public life.

For he always seemed able to find protectors, senior honourable figures who admired his energy, like the headmaster of Dover College, the Principal of Brasenose and Mrs Thatcher, who did not look too closely into the obscurity of certain aspects of his life. Mr Justice Caulfield was just the latest in a long line, though one wonders whether he and the jury would have made anything of this book had it been available at the time of the libel trial.

This is a man, claims his unauthorised biographer, 'for whom real life was at best a good idea'. So interview followed inter- view, and after Wellington (a Somerset school not the College) there was the tramp steamer through the Panama Canal, the million pounds raised for Oxfam, the dinner at which Macmillan sat down with the Beatles. They were not all leakages, just the odd smudge or two when reality flagged.

Macmillan did not come, though Jeffrey Archer told journalists he had. The Beatles came but only because Jeffrey, for once, was caught out in a leakage. He had told Oxfam that the Beatles had agreed to support Oxfam; Oxfam had told the Daily Mail. It was only when the charity interro- gated Jeffrey Archer and found this was not true that they applied genteel black- mail on the group's manager and in shared embarrassment the Fab Four came to Oxford.

And the amazing career rolled on. He invented himself, and nobody checked, not schools or university departments or jour- nalists or even the Conservative Party. In an age where we are always being warned about the amount of information available on all of us, this remarkable man just supplied his own.

His cheek was staggering. At Oxford, getting hold of a recording of Churchill's wartime speeches and hoping to auction them for charity, Churchill himself being too infirm to sign them, he got the Daily Mail to sponsor a visit to the White House where LBJ, then in the middle of the Vietnam War, for some reason did. Archer finally left Oxford and became director of a charity designed to raise funds for, and I write this down as I found it in the book, safer childbirth. He got himself elected to the GLC, informing the Evening News that he had studied engineering in California. He became a fund-raiser for the United Nations Association, though there was a hiccup over expenses. But by then he had formed his own freelance fund-raising company for charities. Harold Wilson re- fused to speak at one of his events, having discovered that Archer, on a percentage, stood to clear £75,000 from the evening.

In spite of this, the irresistible rise continued. Informing the committee that he would come north by helicopter, Archer came by train and was selected as Con- servative candidate for Louth. Interviewed about these stories, Archer, tears in his eyes, is said to have implored the reporter to think of his (Archer's) family, and then slapped a writ on the paper. He became an MP and Reveille, after an interview, in- formed its readers that he was an Oxford graduate.

Then, rushing in the classic way of young Tories towards his first million by the age of 30, he fell in with some Canadian share-pushers who took him for £270,000 (though he was later to speak of £427,727). He had borrowed this, his main creditor served a writ of bankruptcy on him, and he stopped being an MP. If you know your Winter's Tale, some of this may sound familiar to you. 'I know this man well; he hath been since an ape- bearer; then a process-server, a bailiff; then he compassed a motion of the Prodig- al Son, and married a tinker's wife within a mile where my land and living lies; and, having flown over many knavish profes- sions, settled only in . . Jeffrey became a best-selling author. But Jeffrey, you can't write,' protested an old friend when told of his intention. Jeffrey replied that it had nothing to do with writing; he, Jeffrey, would produce a best-seller. And so eventually he did. But even when this was a long way off he was announcing that Warner Brothers had bought the film-rights, and telling Demps- ter that he had already made £220,000 from his first book; both statements duly appeared in the papers. What didn't was his rather endearing enquiry of his pub- lisher as to whether he stood a chance of the Nobel Prize. He was told, no.

There were other books, one journalist sneakily making a note of a correction in the author's own hand which he had seen on a proof: 'He unziped [sic] her skirt and caressed her gently . . .'. The books were shamelessly publicised (Archer even taking the bookstall attendant at Reading station out to lunch), and began to sell in large numbers. He described himself as an old- fashioned storyteller, though there were Whispers that his success owed much to his editors, one of whom is quoted as telling him, 'Am I allowed to tell you what I think of this book, or do I have to be polite?' His success may puzzle those of you who have tried to read one of the books and found them a series of flat statements, 'He did this. . . . then he did that.' His biog- rapher tries his hand at lit crit and finds that any attractive woman either has a business qualification or has long hair falling loose and wayward to her shoulders.

Kane and Abel was sold for paperback in America for half a million dollars. I re- member making these notes when it appeared subsequently as a mini-series (for though Jeffrey had announced that Otto Preminger had bought the film rights they went to London Weekend Television): 'It began at 8. At 8.15 history came calling ("Your father gets to ride on a new ship all by himself." "Not the Titanic?"). At 8.25 the First World War broke out. Ten minutes later the First World War was over. At 8.36 the Russian Revolution broke out . .

Jeffrey Archer went on Desert Island Discs and chose as one of his records, 'Oh Lord, It's Hard to be Humble (When You're Perfect in Every Way)'. One of the athletes who had known him at Oxford phoned another after hearing the program- me, 'Tell me, which eight stories would you tell on your desert island?'

Then there was the Conservative Party and Jeffrey, sporting a badge which said 'I'm a Deputy', was its Deputy Chairman, advising the young on unemployment (he denied there was such a thing), and Ulster on its future (Ian Paisley advised him to see a psychiatrist). And then there was Moni- ca. And Justice Caulfield. And the rough skin on a man's back. 'THERE'S NO SPOTS ON MY JEFFREY', howled the Daily Mirror happily. And the judge's amazing summing-up reproduced in full in the Daily Telegraph. And the £500,000 damages against the Star. A friend of mine, walking in a street in London, was hailed by a taxi-driver he had never seen before. 'He got orf, mate.' He did not know who the man was talking about. 'He bloody has, he bloody has,' said the man, shaking his head in wonder and crashing his gears.

And there was Mary, for the first time a public figure. The brilliant, the beautiful, the lady who by her own admission cannot pass a cushion without straightening it, the choir-mistress, the lady who has degrees and is an authority on her solar chemistry or whatever it is. She rises like a cold tower out of the frantic activity and the fantasy. The story, you must admit, has everything, including the mystery of what Mary is doing as one of the main characters. Even the great Wogan came near to asking her on his chat-show as to what she had ever seen in Jeffrey.

The unauthorised biographer Jonathan Mantle finds her as mysterious as the rest of us and contents himself with turning her into a figure of fun. The day after the trial Mary 'rests that brilliant mind'. It is also a brilliant mind that forgets to turn an iron off so that it burns into a board. There is the famous story of how, pregnant and suspecting the birth was near, she went to a library to see what she should do next. Mr Mantle takes up the tale. 'The book appears to have recommended a short course of cycling, for she then got on her bicycle, rode to the station and boarded the London train.'

Mr Mantle appears not to like either Archer very much, and it gets to the point where he is unable to mention Jeffrey by name, referring to him variously as 'the would-be Nobel laureate', 'the man who once played the part of Puck', 'the world's greatest storyteller'. These heavy sneers are self-defeating, for you begin to feel the beginnings of sympathy for the old self- publicist who at first encouraged this book, introduced his friends, and then refused Mr Mantle an interview.

It is repetitive. When the press appear they are either 'overweight' or 'overpaid' (though there is a bleak little glimpse of the present editor of the Daily Express at his beginnings). It is also irritating to have Jeffrey's doings held out at arm's length before an almost permanent backdrop of world events (`Six weeks after Jeffrey's birthday Hillary and Tensing climbed Everest . . .').

But you will find it impossible to put this book down. Mantle quotes a Central Office man, anonymous, who says that Jeffrey is now 'destroyed'. I doubt this very much, having just received a publicity package for his impending volume of short stories. This contains a colour photograph (of a smiling Jeffrey in Prince of Wales tweed), the news that Saatchi and Saatchi are launching a £50,000-publicity cam- paign, an invitation to meet the great man, and a specimen story.

The last is vintage Jeffrey Archer, a succession of events flatly related. But then, how much invention can a man have after the masterwork of his own life? Having no sense of humour he is insulated against its absurdity. As Mantle notes, he is a man for our times.

Previous page

Previous page