Demolishing the growth god

WILFRED BECKERMAN

The 'Torrey Canyon' disaster could hardly have provided a more appropriate setting for Dr Mishan's brilliant book on the 'clisamenities' associated with economic growth, 'such as the postwar development blight, the erosion of the countryside, the "uglification" of coastal towns, the pollution of the air and of rivers with chemical wastes, the accumulation of thick oils on our coastal waters . . .' and so on.

We economists tend to keep quiet about the `disamenities' of economic growth. As Mishan points out, they have their ritual mention in the odd footnote, of course, but they do not fit very neatly into the scientific-looking mathe- matical formulations that are so popular among economists. Economists prefer their public image to combine modesty with scientific de- tachment; we' are only humble economists; not our job to decide what people should want; and anyway, that would be an unscientific value judgment. Here, at last, a deservedly highly respected economist has taken the trouble to write a book that is intelligible to the layman, in which he challenges the assumption that economic growth automatically provides greater economic welfare. That economic growth has an ugly side is not a new idea, of course, and the importance of this book lies in the fact that the assumption is being chal- lenged by a member of the economics profes- sion, which could be presumed to have a vested interest in the notion that economic growth leads to welfare, and not by a poet or by Freud in a period of relaxation from psychoanalysis.

As long as the assumed link between growth and welfare is conceded, it follows that if one wants more welfare—and who doesn't?-4We have no choice but to pursue economic growth relentlessly, without regard to its minor, un- desirable side effects. But once the assumption is seen to be false, whole new areas of choice are opened up. Society ought then to choose between those ingredients of growth that really added to welfare and those that subtracted from it, as well as between acceptable sacrifices in the interests of more output and unaccept- able sacrifices and social strains.

The assumption that society must seek growth at almost any price has flourished partly because the `disamenity' skeleton .is usually only referred to in whispered footnotes. Dr Mishan talks about this skeleton in public, drawing our attention to all its details, ranging from the stock textbook examples, such as the smoke from factory chimneys, to the 'more general social afflictions such as industrial noise, dirt, stench, ugliness, urban sprawl, and other features that jar the nerves and impair the health.' He points out that our access to can air, beautiful surroundings and so on is left with- out legal protection only because, unlike other property such as land, there are no identifiable quanta for establishing that one has been Ais- possessed of some of these scarce goods. This does not make them less' scarce or less valu-

able. Equally effective is the way he debunks the Buchanan approach to the automobile problem, by means of a parable about a society in which everybody is free to carry fireams. Finally, Mishan severs the link between eco- nomic growth and economic welfare by (a) exposing, along Galbraithian lines, the myth of consumers' sovereignty and the way that the market provides not so much a 'want-satisfy- ing' mechanism as a 'want-creating' mechanism, and (b) reminding us of the plausible hypothesis that one's welfare depends less on one's own absolute standard of living than on one's position relative to others.

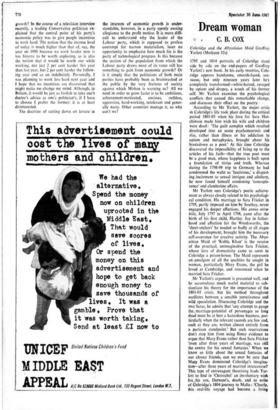

But this is far from the end of Mishan's demolition of the growth god, even though it would be quite enough. The most impressive part of this book is the discussion of the harm- ful effects of economic change on human per- sonality and behaviour. 'The more affluent a society the more covetous it needs to be. Keep a man covetous—achievement-motivated is the approved term—and he may be kept running hard to the last day of his life.' Even though modern man 'successfully ignores the message of each and every advertisement, their cumu- lative effect over time in teasing his senses and tapping repeatedly at his greeds, his vanity. his lusts and ambitions, can hardly leave his character unaffected. Again, by drawing his attention daily to the mundane and material, by hinting continually that the big prizes of life are the things that only money can buy, the influences of advertising and popular journalism conspire to make a man restless and --discontented with his lot.' Mishan draws a con- vincing picture of the links between rapid eco- nomic growth and many of the undesirable changes in society and human personality, such as the growing sense oif insecurity and the dis- ruption of the family unit (accompanying the pace of technological advance and contempt for the obsolete knowledge of one's elders), the reduction of communications between human beings, the claustrophobia engendered by the loss of any sense that we are living in a huge world of variety and mystery, and the way that these and other developments have probably contributed to the growth of cynicism and violence.

But it may well be that the evils of indus- trialisation on which Mishan concentrates are typically those that strike the middle classes, whose basic material needs are already met, The working classes may still have enough to gain from growth to blind them to what they lose. And as for the really rich, if economic growth means that their old retreats on the

d'Azur have been flooded with congds payes, they can still go to the Bahamas and in twenty years' time there will still be the Himalayas or the moon. It is the middle classes who stand to lose most now. In the old days, even lower-middle-class mothers had maids to do the washing up, so that for them the mass availability of washing machines, dishwashers, automobiles and the like does not carry with it the same release from drudgery and from living in unpleasant, cramped surroundings as it does for the working classes. To the middle classes, economic growth means that when they arrive at Delphi it is full of other people who spoil any place. Though Mishan is no doubt right in saying that slower travel would mean that the world would be less uniform and vul- gar. it would also mean that the American typists with two weeks' vacation would have to spend it at home.

This difference between the interests of the middle classes, who don't really have a political party to represent them, and the rest may help answer another question that Mishan has not been able to raise in this short book : namely, why is it that the two main political parties are equal in their reverence for economic growth? In the course of a.television interview recently, a leading ConserVative politician ex- plained that the central point of his party's economic policy was to give people incentives to work hard. The notion that the income level of today is much higher than that of, say, the year An 1000 because we work harder now is too bizarre to be worth exploring, as is also the notion that it would be worth our while working, not just 2 per cent harder this year than last year, but 2 per cent harder the follow- ing year and so on indefinitely. Personally, I was planning to work less hard next year and I hope that no incentives are discovered that might make me change my mind. Although, in Britain, it would be just as foolish to take one's doctor's advice as one's politician's, if I have to choose I prefer the former; it is at least disinterested.

The doctrine of cutting down on leisure in the interests of economic growth is under- standable, however, in a party openly owning allegiance to the profit motive. It is more diffi- cult to understand why the leader of the Labour party, which is supposed to profess contempt for narrow materialism, loses no opportunity to emphasise how much his is the party of technological progress. Is this because the section of the population from which the Labour party draws most of its votes still has something to gain from economic growth? Or is it simply that the politicians of both main parties have probably been as brainwashed as the public by the very features of society against which Mishan is warning us? All we need in order to grow faster is to be ambitious, achievement-motivated, envious, ruthless, aggressive, hard-working, intolerant and gener- ally nasty. Other countries manage it, so why can't we?

Previous page

Previous page