Dream woman

• C. B. COX

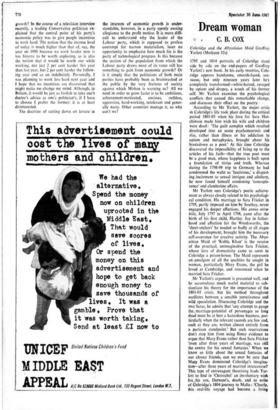

Coleridge and the Abyssinian Maid Geoffrey Yarlott (Methuen 55s) 1795 and 1814 portraits of Coleridge stand side by side on the end-papers of Geoffrey Yarlott's new book. In his early twenties; Cole- ridge appears handsome, smooth-faced, sen- suous, but only nineteen years later. he's completely transformed—white-haired, ravaged by opium and dropsy, a wreck of his former self. Mr Yarlott examines the psychological conflicts that caused this remarkable change, and discusses their effect on the poetry.

According 'to Mr Yarlott, the major crisis in Coleridge's life took place during the critical period 1801-03 when his love for Sara Hut- chinson made him wish his wife and children were dead: 'The guilt complex which resulted developed into an acute psychoneurosis and this, rather than illness or his addiction to opium and metaphysics, brought about his breakdown as a poet.' At this time Coleridge discovered the impossibility of living up to the articles of his faith—that the true poet must be a good man, whose happiness is built upon a foundation of virtue and truth. Whereas during the 1798-99 trip to Germany he had condemned the waltz as 'lascivious,' a disgust- ing,incitement to sexual intrigue and adultery, he now found himself condoning 'concupis- cence' and clandestine affairs.

Mr Yarlott sees Coleridge's poetic achieve- ment as always closely related to his psychologi- cal condition. His marriage to Sara Fricker in 1795, partly imposed on him.by Southey, never engaged his deeper affections. His annus mira- bilis, July 1797 to April 1798, came after the birth of his first child, Hartley. Joy in father- hood and affection for the Wordsworths, the 'sheet-anchors' he needed so badly at all stages of his development, brought him the necessary self-assurance for creative activity. The Abys- sinian Maid of 'Kubla Khan' is the reverse of the practical, unimaginative Sara Fricker, whose love of domesticity came to seem to Coleridge a prison-house. The Maid represents an tinnalgam of all the qualities he sought in woman, particularly Mary Evans, the girl he loved at Cambridge, and renounced when he married Sara Fricker.

Mr Yarlott's argument is presented well, and he accumulates much useful material to sub- stantiate his theory for the importance of the 1801-03 crisis; but his method throughout oscillates between a sensible tentativeness and wild speculation. Discussing Coleridge and the two Saras, he admits that 'any attempt to gauge the.marriage-potential of personages so long dead must be at best a hazardous business, par- ticularly when the relevant records are few and, such as they are, written almost entirely from a partisan standpoint.' But such reservations don't stop him from using flimsy evidence to argue that Mary Evans rather than Sara Fricker 'even after three years of marriage, was still the centre for his sexual fantasies.' When we know so little about the sexual fantasies of our closest friends, can we ever be sure that Maw Evans dominated Coleridge's imagina- tion=-after three years of married intercourse? This type of extravagant theorising leads Yar- lott to find in `Christaber an involuntary wish for:, his son, Derwent's, death, and to write of €oleridge's 1804.journey to Malta: .*Clearly, this . real-life voyage had become a living

allegOtY of the Ancient Mariner's -experiences.' Clearly?

The major weakness is that Mr Yarlott places too much emphasis on the psychological rather than literary influences on a poet's style:. These days I feel only exasperation and rage when I'm told that Kubla Khan's pleasure- dome is 'an inverted breast-image.' Mr Yarlott talks of 'Kubla's • fussy little paradise,' asso- ciating his pleasure garden with a rejected gen- suality. The 'incense-bearing tree' suggests a manufactured perfume rather than deliCate, natural fragrance,' he tells us, without men- tioning the obvious religious suggestions.' In his view, this sensual paradise perhaps signifies Sara's former sexual• attractiveness for Cole- ridge: 'He had chosen to fix his "empire" on "spotless -Sara's breast," though recognising that Sara could never be more to him than "an instrument of low desire."' This is pushing psychological explanation far beyond its proper bounds.

Mr Yarlott ends his book by arguing in- terestingly that Coleridge's analysis of his own psychological problems influenced his theory of the 'whole man.' And perhaps I've been too unkind to a book so well documented, which does reach valid conclusions on the more ex- plicitly autobiographical sections of Coleridge's work. Mr Yarlott is unfortunate that his book must have been in proof when George Watson's Coleridge the Poet appeared, with its strong emphasis. on literary antecedents. But may I conclude by suggesting that when Coleridge wrote 'Abyssinian maid' the person he had in mind was someone exotic from a far-off land —an Abyssinian maid?

Previous page

Previous page