CHESS

Never be old

Raymond Keene

this week I want to recall a most promising young player, Ian Wells, who almost ten years ago died in a tragic accident. Ian was one of the brightest hopes of British chess, already capable at the age of 14 of holding his own in international tournaments. He was well versed in theory and had a sharp tactical eye. Had he lived he would certainly have gone on to become a grandmaster. I played just one game against him and it was a most exciting battle. In this game I employed a variation which I believe I invented (Bednarski-Keene, Hanover 1976, was the first time I know that the idea was used) and I did not expect that Ian would be fully conversant with its subtle- ties. Indeed, even in many contemporary openings texts this invention based on 7 . . . a6 is often covered in quite inadequate fashion.

Contrary to my expectations, however, Ian Wells knew the opening perfectly well and handled the middle game complica- tions with superb aplomb. I was particular- ly impressed with his bold piece sacrifice on the 23rd move which rescued him from a seemingly critical situation, It is most sad that he is no longer with us to entertain us with such sparkling ideas.

I.D. Wells — R. Keene: Morecambe 1980; Modern Defence.

1 e4 g6 2 d4 Bg7 3 Nc3 d6 4 f4 Nc6 One of the sharpest variations of the Modern Defence. 5 Be3 5 Nf3 is not an error but gives Black a very clear plan of campaign of pressure against d4. 5 . . . Nf6 6 Bet This move became very fashionable after Robert Byrne used it in a model game to defeat me at Hastings, 1972. Nevertheless 6 Qd2 is probably stronger. 6 . . . 0-0 7 Nf3 a6 This is my special variation which I believe I invented. I tried 7 . . . Bg4 in the game against Byrne and lost convincingly after 8 e5! 8 e5 8 0-0 b5 9 e5 Ng4 10 13c1 Bb7 11 d5 (White seems to be playing aggressively but in fact his centre is on the verge of collapse after all this.)

11 . . Na5 12 e6 f5 13 a4 b4 14 Na2 c6 15 Khl Qb6 16 Qe1 b3 17 h3 Nf6 with a big advantage to Black (0-1.33) Morris — Keene, Sydney 1979. Other moves are: (i) 8 a4 e6 9 h3 Ne7 10 g4 b6 11 Nd2 c5 12 dxc5 bxc5 13 Nc4 d5 14 Bxc5 Nd7 15 Bxe7 Qxe7 16 exd5 Bb7 17 Qd2 exd5 18 Nxd5 Qe4 19 0-0-0 BxdS 20 QxdS Qxe2 21 Rhel Qf2 22 Qxd7 Qxf4+ 23 Ne3 Rab8 24 c3 Rfe8, ultimately 0-1 Marjanovic — Keene. Skara 1980. (ii) 8 d5 Na7 9 a4 c5 10 0-0 Bd7 11 Nd2 b5

12 e5 Ne8 13 Nf3 Nc7 14 axb5 Naxb5 15 Ne4 Bf5 16 Ng3 dxe5 17 Nxf5 gxf5 18 c4 exf4 19 Bxc5 Nd6 20 Nd4 Qd7 21 Nc6 Rfe8 22 Rxf4 Ne4 23 Ba3 e6 24 Khl exd5 28 exd5 1/2-1/2 (Georgadze Keene, Baguio City 1980) 8 . . . Ng4 9 Bgl b5 10 Ng5 Nh6 Very risky indeed is 10 . . f6 11 Nxh7 Kxh7 12 Bxg4 fxe5 13 Bf3 Bd7 (13 . . . Qe8!?) Vera — Goodman, Students' Olympiad, Mexico City, 1978. 11 Bf3 Bd7 12 Qe2 b4 A prepared improvement over 12 . . Qc8 which had been played before but which had come to grief in a game between Nigel Povah and David Good- man, Phillips and Drew Knights, 1980. The attack with Black's 'b' pawn is considerably more challenging. 13 Nce4 If 13 Nd5 f6 14 exf6 exf6 15 Ne6 Bxe6 16 Qxe6+ Kh8 threatening 17 . . . Re8 with a good game for Black. Alterna- tively 14 e6 fxg5 15 exd7 Qxd7 followed by - Nf5. 13 . . . f6 14 e6 Be8 Black avoids 14 . . . fxg5 15 exd7 Qxd7 16 NxgS when White dominates the light squares. The move played offers an exchange sacrifice for a pawn in the interests of eroding White's pawn centre. 15 Nh3 15 d5 is no improvement e.g. 15 . Nay 16 Nh3 f5 followed by the raid 17 . . . Bxb2. 15 . . . f516 NegS Nxd4 17 Bxd4 Bxd4 18 0-0-0 After 18 Bxa8 Black interpolates 18 . . . Bxb2. 18 . . . c5 Black could also have played the immediate 18 . . . Bg7 to avoid any counter-sacrifice of the exchange on d4. 19 Bxa8 QxaS 20 Nf3 Here it was possible to return the exchange by means of 20 Rxd4 cxd4 21 Rdl with an unclear position. 20 . . . Bg7 21 NhgS a5 22 Nf7 a4 Black should shun 22 . . Nxf7 23 exf7+ Bxf7 24 Qxe7 when, with Ng5 to come, Black's position starts to crumble. 23 Nxd6! The white knight on f7 looks dangerous but is achieving very little. This sacrifice is the best way of stirring things up and creating distinct counter-chances. 23 . . . b3 I thought it important to open some lines against the white king, even though this move rather spoils Black's imposing phalanx of queenside pawns which should perhaps culminate in adv- ance . . . a3. If instead 23 . . . exd6 24 Rxd6 gives White an enormous amount of play with 25 e7 and 26 Rd8 very much in the air. 24 a3 bxc2 25 Qxc2 exd6 After the game Ian Wells sug- gested that 25 . . . Bc6 and if 26 Nc4 Be4 would have been a superior winning try for Black. 26 Rxd6 Qb7 27 Rel Qc7 28 Redl Ng4 29 Qe2 Qe7 Probably 29 . . Bd4 is stronger since 30 Ra6 is met by 30 . . . Ne3. 30 Khl Nf6 31 Qc4 Kh8 32 Ne5 Ne4 33 Rd8 g5 34 Kal Wells sees the devilish trap 34 R1d7? Bxd7 33 Rxd7! Qxd7!' 36 exd7 Nd2+ forking White's king and queen. The text prepares the rook invasion on the seventh

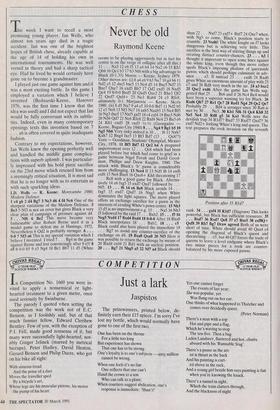

Position after 35 R1d7

rank. 34 . . . gxf4 35 Rld7 (Diagram) This looks powerful, but Black has sufficient resources. 35 . . Bxd7 36 Rxd7 Qe8 37 e7 BxeS 38 exf8Q+ Qxf8 39 Rb7 Bg7 Draw agreed Both of us were short of time. White should avoid 40 Qxa4 c4 opening the diagonal of Black's queen and threatening. . . c3, but 40 Qf7 forces the trade of queens to leave a level endgame where Black's two minor pieces for a rook are counter- balanced by his more exposed pawns.

Previous page

Previous page