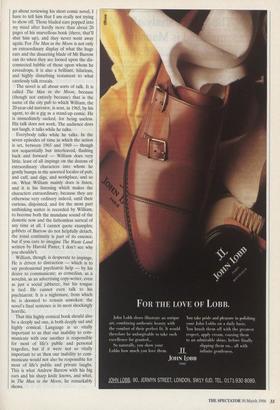

Careless talk costs souls

Alan Coren

THE MAN IN THE MOON by Andrew Barrow Macmillan, £14.99, pp. 220 Very near the top of the right-hand wing of Hieronymous Bosch's nerve- boggling triptych, 'The Garden of Earthly Delights' — which is to say just below the conflagrant gates of Hell and just above the man whose arse has fallen off — there is an image as unsettling as any that this teeming post-lapsarian nightmare has to offer.

It is a pair of giant pink disembodied ears, with, between them, a glinting knife- blade held at an angle reminiscent of jollier things. But that ironic nudge is only a fall- from-grace-note which the incorrigible wag in Bosch was unable to resist: the true function of this grisly artefact, mounted on the tiny writhing bodies of the scalded damned, is to alert us to oral betrayal. Careless talk costs souls.

Now, lest Andrew Barrow irritably dis- miss this as an unacceptably poncey way to go about reviewing his short comic novel, I have to tell him that I am really not trying to show off. Those bladed ears popped into my mind after hardly more than about 20 pages of his marvellous book (there, that'll shut him up), and they never went away again. For The Man in the Moon is not only an extraordinary display of what the huge ears and the dissecting blade of Mr Barrow can do when they are loosed upon the dis- connected babble of those upon whom he eavesdrops, it is also a brilliant, hilarious, and highly disturbing testament to what carelessly talk reveals.

The novel is all about sorts of talk. It is called The Man in the Moon, because (though not entirely because) that is the name of the city pub to which William, the 20-year-old narrator, is sent, in 1965, by his agent, to do a gig as a stand-up comic. He is immediately sacked, for being useless. His talk does not work. The audience does not laugh, it talks while he talks.

Everybody talks while he talks. In the seven episodes of time in which the action is set, between 1965 and 1969 — though not sequentially but interleaved, flashing back and forward — William does very little, least of all impinge on the dozens of extraordinary characters into whom he gently bumps in the assorted locales of pub, and caff, and digs, and workplace, and so on. What William mainly does is listen, and it is his listening which makes the characters extraordinary, because they are otherwise very ordinary indeed, until their curious, disjointed, and for the most part unthinking natter is recorded by William, to become both the mundane sound of the demotic now and the fathomless surreal of any time at all. I cannot quote examples, gobbets of Barrow do not helpfully detach, the tonal continuity is part of its essence, but if you care to imagine The Waste Land written by Harold Pinter, I don't see why you shouldn't.

William, though, is desperate to impinge. He is driven to distraction — which is to say professional psychiatric help — by his desire to communicate; as comedian, as a novelist, as an advertising copy-writer, even as just a social jabberer, but his tongue is tied. He cannot even talk to his psychiatrist. It is a nightmare, from which he is doomed to remain unwoken: the novel's final sentence is its most shockingly horrific.

That this highly comical book should also be a deeply sad one, is both deeply sad and highly comical. Language is so vitally important to us that our inability to com- municate with one another is responsible for most of life's public and personal tragedies, but if it were not so vitally important to us then our inability to com- municate would not also be responsible for most of life's public and private laughs. This is what Andrew Barrow with his big ears and his sharp knife knows, and what, in The Man in the Moon, he remarkably shows.

Previous page

Previous page