ARTS

Museums

Terrible, beautiful weapons

Martin Vander Weyer visits the new Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds

It is hard to think of anything less politi- cally correct. Within a fortnight of one of the most unspeakable acts of violence in national memory, here is a brand-new 'leisure facility', devoted to the means of death and destruction, in which children are offered 'sensory handling experiences' with weapons of war and an actor in Edwardian tweeds tells you that tiger- shooting is best accomplished by attracting the prey with 'a woman or a goat tethered to a stake'. But the new Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds (open to the public from 30 March) is a splendid achievement, and all the more so for pulling no punches in relation to the problematical nature of its subject matter.

Splendid, but I offer that opinion with reservations about the building itself, and about the extent to which the language of commercial leisure has intervened. To label it a theme park, as Brian Sewell was quick to do, is to belittle an attempt to combine tradi- tional museumship with the kind of 'interac- tive' display which is more likely to impinge on the shortened attention span of burger- fed, video-game addicts. But the organisers have themselves chosen to call the place, even more infelicitously, a 'centre for the performing arms', and you don't have to be as fastidious as Sewell to find some of their initiatives grating: the 'corporate entertain- ment' brochure, for example, suggests that your guests might enjoy an Elizabethan ban- quet in the 'Tournament Gallery' or a sushi evening in the 'Japanese Tea Garden'. And after, 'Why not let them loose on one of our exciting indoor shooting ranges?'

Modern museums have to find ways of making ends meet, however, and this one has relied on private enterprise from the start. Whilst the Royal Armouries itself has existed as an arsenal in the Tower of Lon- don for the past 900 years, Royal Armouries (International) plc, the company set up to develop and operate the new museum, is a more recent creation. It is backed by, among others, Yorkshire Electricity, the Bank of Scotland and a catering firm called Gardner Merchant.

The original plan seems to have included the possibility of sponsorship for each sepa- rate element of the museum. That Japanese tea garden (about as relevant to armouries as an English cricket pavilion) is a bit of a give-away: clearly it was hoped that a large yen cheque would finance, let us say, the Canon Copier Gallery of Orien- tal Warfare. But this ploy worked only with the Yorkshire Electricity Hall of Steel, a 100 ft-high cylindrical stairwell lined with multiple arrangements of blades, muskets and armour. Looking up at these from ground level is, by the way, a disconcerting experience; it reminded me of an encounter with the cartoonist Charles Addams, who told me he had a collection of loaded crossbows mounted around the walls of his New York dining-room, one pointed at each chair.

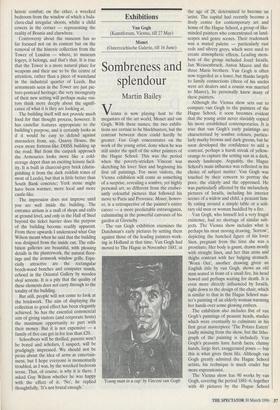

The rest of the Royal Armouries remains unsponsored, and it is not hard to see why Japanese companies shied away from the Elephant armour, Indian, Mughal, c. 1600, in the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds opportunity. A reminder of their ancestors' warlike demeanour is the last thing with which modern Japanese sales executives would want their brand-name linked.

Which brings us back to the museum's philosophical dilemma: war is bad, but it is sometimes just and is always important. It brings out the vilest of human behaviour, but also the best. Weapons are terrible, but (as the Queen was criticised for saying when she opened the museum) they can also be beautiful, and their craftsmanship can be admired. To spend £42.5 million on an all- dancing display of them might be con- demned as bad taste, but the Armouries collection already existed, largely unseen in the bowels of the Tower of London, and there is obvious value in making it accessible — not to mention a statutory duty to do so on the part of its curators.

What they have done, under the direc- tion of Guy Wilson, Master of the Armouries, will sound gimmicky, but (as far as I could judge last week, when it was still being assembled, and many of the live exhibits were uniformed security guards hired to prevent the collection leaving with the decorators) it works very well. Each major gallery — War, Oriental, Self- Defence and Hunting — contains a mix- ture of the fixed displays you would expect to see, plus a range of activities and gadgets besides. Outside the main building is a 'craft court' of working gunsmiths and armourers, as well as a menagerie of hawks, dogs and horses, and a 'tilt-yard', a grassy arena for jousting and falconry — with the emphasis on authenticity, as much as can be achieved on a site overlooked by grimy Victorian warehouses.

Some of the display items, like the Indi- an elephant armour, are very fine indeed. Others — parents beware — are surprising, like a suit of mediaeval English armour with an enormously prominent codpiece: perhaps, quite literally, the gallant knight's lunch box. Behind some of the display cases are miniature cinemas, showing film sequences of military history and tactics. There are computer terminals on which ancient battles can be re-fought, with the operator choosing whether to attack or retreat. There is a 'Newsroom' offering video footage of the world's trouble spots. In the central spaces there are actors pro- viding brief cameos and fight scenes in a tournament square and a Japanese dohyo (gymnasium). This is not for the squeamish: they go at each other vigorously with pole-axes, the commentator observing that 'you have to immobilise your knight before despatching him', preferably with a blow straight through the visor.

I enjoyed all of it except, for some rea- son, the Battle of Pavia (France v. Ger- many, 1525), which features a strangely kitsch static display and a loud, breathless commentary in the style of Brian Hanrahan reporting from the Falklands. And I was troubled by the final display in the War Gallery: on the one side, a star wars mon- tage representing the 'seductive myth' of heroic combat; on the other, a wrecked bedroom from the window of which a bala- clava-clad irregular shoots, whilst a child cowers in the corner — representing the reality of Bosnia and elsewhere.

Controversy about the museum has so far focused not on its content but on the removal of the historic collection from the Tower of London — where, to museum fogeys, it belongs, and that's that. It is true that the Tower is a more natural place for weapons and their use to be the centre of attention, rather than a piece of wasteland in the industrial quarter of Leeds. But armaments seen in the Tower are just pic- ture-postcard heritage; the very incongruity of their new setting will perhaps make visi- tors think more deeply about the signifi- cance of what it is they are looking at.

The building itself will not provide much food for that thought process, however. It has castellar features appropriate to the building's purpose, and it certainly looks as if it would be easy to defend against marauders from, say, Quarry House, the even more fortress-like DHSS building up the road. But from the carpark approach the Armouries looks more like a cold- storage depot than an exciting leisure facil- ity. It is built in charcoal-grey brick (distin- guishing it from the dark reddish tones of most of Leeds), but that is little better than South Bank concrete; York stone might have been warmer, more local and more castle-like.

The impression does not improve until you are well inside the building. The entrance atrium is a mall of shops and cafés at ground level, and only in the Hall of Steel beyond the ticket barrier does the purpose of the building become readily apparent. From there upwards I understood what Guy Wilson meant when he said that the building was designed from the inside out. The exhi- bition galleries are beautiful, with pleasing details in the plasterwork, the natural floor- ings and the ironwork window grills. Espe- cially attractive are the rectangular beech-wood benches and computer stands, echoed in the Oriental Gallery by wooden shoji screens. It is a pity that the quality of these elements does not carry through to the totality of the building. But still, people will not come to look at the brickwork. The aim of displaying the collection to good effect has been elegantly achieved. So has the essential commercial aim of giving visitors (and corporate hosts) the maximum opportunity to part with their money. But it is not expensive — a family of five can get in for less than £20. Schoolboys will be thrilled, parents won't be bored and scholars, I suspect, will be grudgingly impressed. We should not be pious about the idea of arms as entertain- ment, but I hope everyone is momentarily troubled, as I was, by the wrecked bedroom scene. That, of course, is why it is there. I asked Guy Wilson whether he was happy with the effect of it. 'No', he replied thoughtfully, 'It's not brutal enough.'

Previous page

Previous page