IN THE GUERRILLAS' MOUNTAIN HIDEOUT

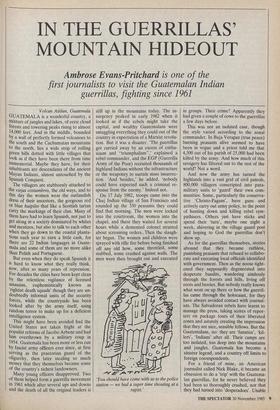

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard is one of the

first journalists to visit the Guatemalan Indian guerrillas, fighting since 1961

Volcan Atitlan, Guatemala GUATEMALA is a wonderful country, a mixture of jungles and lakes, of eerie cloud forests and towering peaks rising to almost 14,000 feet. And in the middle, bounded by a wall of perfectly formed volcanoes to the south and the Cuchumatan mountains to the north, lies a wide strip of rolling green hills dotted with little villages that look as if they have been there from time immemorial. Maybe they have, for their inhabitants are descendants of the ancient Mayan Indians, almost untouched by the Spanish Conquest.

The villagers are stubbornly attached to the viejas costumbres, the old ways, and to this day the women wear the outlandish dress of their ancestors, the gorgeous red or blue huipiles that like a Scottish tartan carry the markings of their clan. Many of them have had to learn Spanish, not just to get along in a society dominated by whites and mestizos, but also to talk to each other When they go down to the coastal planta- tions each year to earn a little cash, for there are 22 Indian languages in Guate- mala and some of them are no more alike than Polish and Portuguese.

But even when they do speak Spanish it is hard to know what they really think, now, after so many years of repression. For decades the cities have been kept clean by the relentless vigilance of licensed assassins, euphemistically known as 'rightist death squads' though they are un- doubtedly informal units of the security forces, while the countryside has been looked after by the army itself, using random terror to make up for a deficient intelligence system.

This might have been avoided had the United States not taken fright at the Populist reforms of Jacob° Arbenz and had him overthrown by a military coup in 1954. Guatemala has been more or less run by fascist army officers ever since, at first serving as the praetorian guard of the oligarchy, then later stealing so much money that they themselves became some of the country's richest landowners. Many young officers disapproved. Two of them helped form a guerrilla movement in 1961 which after several ups and downs and the death of all the original leaders is still up in the mountains today. The in- surgency peaked in early 1982 when it looked as if the rebels might take the capital, and wealthy Guatemalans were smuggling everything they could out of the country in expectation of a Marxist revolu- tion. But it was a disaster. 'The guerrillas got carried away by an excess of enthu- siasm and "triumphalism",' explained a rebel commander, and the EGP (Guerrilla Army of the Poor) recruited thousands of highland Indians without the infrastructure or the weaponry to sustain mass insurrec- tion. 'And besides,' he added, 'nobody could have expected such a criminal re- sponse from the enemy.' Indeed not.

On 17 July 1982, troops came into the Chuj Indian village of San Francisco and rounded up the 350 peasants they could find that morning. The men were locked into the courtroom, the women into the chapel, and there they waited for several hours while a demented colonel strutted about screaming orders.. Then the slaugh- ter began. The women and children were sprayed with rifle fire before being finished off any old how, some throttled, some stabbed, some crushed against walls. The men were then brought out and executed 'You should have come with us to the police station — we had a super time shouting at a rapist.' in groups. Their crime? Apparently they had given a couple of cows to the guerrillas a few days before.

This was not an isolated case, though the style varied according to the zonal commander. In Baja Verapaz (true peace) burning peasants alive seemed to have been in vogue and a priest told me that 4,500 out of his parish of 25,000 had been killed by the army. And how much of this savagery has filtered out to the rest of the world? Not a word.

And now the army has turned the highlands into a vast grid of civil patrols, 800,000 villagers conscripted into para- military units to 'guard' their own com- munities. Some, particularly the conserva- tive `Christo-Pagans', have guns and actively carry out army policy, to the point of hunting down and killing rebel sym- pathisers. Others just have sticks and spend their 'turn', maybe one night a week, shivering in the village guard post and hoping to God the guerrillas don't show up.

As for the guerrillas themselves, stories abound that they became ruthless, punishing peasants that refused to collabo- rate and executing local officials identified with government. Then as the noose tight- ened they supposedly degenerated into desperate bandits, wandering aimlessly through the forests and hills, living off roots and berries. But nobody really knows what went on up there or how the guerril- las came through the holocaust, for they have always avoided contact with journal- ists. The Salvadoran rebels have learnt to manage the press, taking scores of repor- ters on package tours of their liberated zones and astutely creating the impression that they are nice, sensible fellows. But the Guatemalans, no: they are 'fanatics', 'kil- lers', 'Indians' after all. Their camps are too isolated, too deep into the mountains and jungles. Guatemala has become a sinister legend, and a country off limits to foreign correspondents.

For a friend of mine, an American journalist called Nick Blake, it became an obsession to do a 'trip' with the Guatema- lan guerrillas, for he never believed they had been so thoroughly crushed, nor that they had turned into 'desperadoes'. Unable to make contact with the rebels, despite spending weeks in Nicaragua wining and dining Guatemalan exiles, he set off on foot last March with an American compan- ion to make direct contact with the Ho Chi Minh Front of the EGP. They were never seen again. Some say the civil defence shot them, some that the army killed them as they were leaving the rebel zone weeks later, and others, citing supposed EGP sources in Managua say they were executed by the guerrillas.

This last story was readily believed since it is exactly what many people would have expected from the Guatemalan guerrillas. Moreover they swallowed the propaganda put out by the army that the rebels were fragmented and undisciplined: that 'life was cheap in the area and that if the journalists arrived with money the guerril- las might well rob and kill them'. I believed it too, but now I know better for I have since got to know a few of these 'bandits'.

How I and two companions, a Spaniard and an American, came to be with them cannot be told, for lives depend upon discretion. Suffice to say that the Guate- malan resistance organised and planned our trip. We did not know where, or for how long, or with whom we were going. All we were told was that our journey would begin one night at the foot of a volcano, on the shores of what Aldous Huxley once called the most beautiful lake on earth.

Like clockwork it went, as we were passed along a chain of resistance activists, always cheerful though they each faced a certain and hideous death if ever they should be accused by one of the orejas (ears) the army uses to spy on the countryside — or be betrayed by one of us. They led us up through fields of maize, the leaves cutting into our faces, past neglected coffee fincas, and on to a sheltered ridge where five armed combatants were lying in wait. They crowded round eagerly, bub- bling with enthusiasm, and gave us each the hearty guerrilla embrace that so starkly contrasts with the clipped salute of the Guatemalan army. A mercurial Indian called 'Profane' was in charge but it was 'Otto' who did most of the talking. A 22-year-old poet with already six years in the resistance, he told us how he had once been a pacifist, working after school in the slums of Guatemala City, until the murder of his brother gave him no choice but exile or armed rebellion.

We didn't stay there long, just enough time to gobble down some cold beef stew and smoke a damp cigarette, before turn- ing our backs on the lake and starting out on a gruelling march to the headquarters of the Javier Tambriz guerrilla front of the Organisation of the Armed People (ORPA) — sister group of the EGP. For six hours we stumbled through the moun- tains, catching our backpacks on dangling vines, slithering under roots that caught our feet like stirrups and sent us crashing to the ground.

We got a few hours' sleep sprawled anyhow under some pine trees at 9,000 feet but it was too cold and wet to want to linger very long. Then off we went again, our escort cautiously skirting any human settlement so that nobody should see three tall gringos in company with the rebels. It was daytime but might just as well have been night, for the rain was so thick we could hardly see the ground. Down, down, we slid, thousands of feet of grime and mud, crashing from tree to tree, and clutching branches only to find they were spiked with thorns.

We hobbled into the camp to an affec- tionate welcome from some of the finest people I have ever met. They were all standing round the fire beneath a huge canvas fly-sheet, drinking cups of hot soya compound, and chatting away as if it were the junior common room on a busy day between lectures.

n attractive woman of 30 in full combat dress took us over to the fire to dry out. Our escorts had no such privilege, nor did they have any fresh clothes to change into since each combatant only has one uniform, and we realised that these poor creatures spend the long rainy season almost constantly wet. 'It's hard for some- one from the city,' explained our hostess, Anna. 'In winter you're always soaked and in summer when the water dries up you're always dirty.' She was not brought up for such a life. Daughter of an army colonel, she was educated in private Catholic col- leges before studying engineering at Guatemala's San Carlos University where she joined the resistance 12 years ago.

Before we were taken off to our cham- pas, camouflaged tents dug into the hill- side that guerrillas call their home, we were each handed a teaspoon and a bowl of steaming hot food. Rice, beans and maize is usual rebel fare but for us there was a feast of beef, and coffee, and heaps and heaps of chocolate. We never did find out where it all came from, though it certainly didn't come from Nicaragua or Cuba. The Javier Tambriz front is smack in the middle of Guatemala with no land corridor to a neutral country and it seems their food is partly donated and partly sold by villagers in the front's zone of operations, an area perhaps the size of Devon. Where they got the mixed arsenal of rifles, machine guns, bazookas and grenade launchers that lay on

A

trestles in the mess camp is more difficult to say. As for the ammunition, they don't need very much. While government troops fire hundreds of rounds in a single skirmish, giving away their position and often para- lysing their own movements, the guerrillas virtually never use repeating fire and say they can make 150 rounds last a year. Most actions against the army are ambushes with home-made claymore mines, or pinprick attacks designed more to obstruct patrol- ling and demoralise the army that to exterminate soldiers whom the guerrillas know to be mostly Indian conscripts. But though fighting is the purpose of ORPA, a good guerrilla is expected to be something more, a leader for the future. Most can already read and write before they join up, so classes down at the 'school' work on 'raising consciousness'. We went to a seminar. Everybody chipped in with his bit. Some of the girls were too shy to try in Spanish so they made their little speeches in Mam, Quiche, or Tzuhuitil, while biling- ual Indian officers patiently translated for the rest. Nobody questioned ORPA's offi- cial line that the elections are just another counter-insurgency ploy by the army. How could they? Besides, they may be right.

One wondered how the guerrillas them- selves would run the country if ever they came to power; and so, no doubt, do they. The URNG (Guatemalan National Re- volutionary Unity), the loose affiliation of Guatemala's four guerrilla groups, has an impeccable five-point plan that can be thrown straight into the dustbin. These kinds of documents are drafted by exiled intellectuals, to be read by gullible for- eigners. On the nitty-gritty I don't think the rebels have any programme whatsoever. All that can really be described are tendencies, and of those ORPA, commanded by Rodrigo Asturias, son of the Nobel Prize winning novelist Miguel Angel Asturias, is reputedly the most moderate.

Sitting round the camp fire at night we talked for hours about the world. And as ranted furiously about Soviet meddling in Poland and Afghanistan the guerrillas lis- tened quietly, never leaping to defend the Russians and yet never showing any hint of agreement either. Even Pancho', a gold star on the front of his cap denoting the rank of `comandante', was unforthcoming.

He preferred to talk of other countries. The United States, for example, which he optimistically feels will have to grow up one day, and Iran, which taught him the force of religious conviction. `Pancho' is a practical fighter; he has little time for the café theorists who have controlled the communist parties of Latin America for decades and sees no place for Das Kapital in the liberation of Mayan Indians. 'We don't consider the landowners or the rich to be our enemies. Guatemala is a backward country and we need these peo- ple, but they must expect changes.' And quite right too; some of those swine are still paying their workers as little as 25p a day, months in arrears, when the national minimum wage is the hardly exorbitant sum of 75p. A few are also helping the army. 'We warn landowners who are serv- ing as intelligence antennae for the enemy that they will be punished if they continue, and we have had to burn down some farms as many as three times. Eventually they learn . . . . Where they persist, and if they're endangering our own supporters, we have to execute them, but we only do that as a last resort' 'At first it's hard living as a guerrilla,' said sub-lieutenant Geronimo, who had to abandon his wife and three children six Years ago and has had no word from them since. 'But when you come up here to the front you discover this humanity, this fraternity, this friendship that fills the emptiness, that compensates for all the suffering. . . I believe that all of us feel homesick at times, when the mountain turns silent in the early hours of the night, the animals quiet, the moon, the rays of moonlight, the stars — well, you think. But then it passes. You're tired, you sleep, and the next day there are so many things to do, so much to be getting on with.'

Keeping busy is perhaps the only way Geronimo' can contain the explosive pas- sion that lies behind his dour face. A big, strong man of 33, Geronimo has been at different times a teacher, an electrician and the manager of a travelling theatre group in the United States. So when he's not out on combat missions he's down at the 'school' giving classes, or over at the workshop making lethal claymore mines, or rehearsing for one of the weekend 'cultural events'. 'We once put on the Troupe Scene from Hamlet and it went down very well. We were planning to try Romeo and Juliet but our copy of Shake- speare fell to pieces in the rain and, as you know, Shakespeare without the words isn't worth a hell of a lot and we had to give it up. Now whenever we take over a plantation we go through the library to see what they've got, but these landowners don't seem to be too keen on Shakespeare SO we haven't had much luck.'

They do not doubt that eventually they will triumph. 'I'm certain we'll do it,' said Anna. 'If I wasn't I wouldn't be here. I don't like being a loser.' The guerrillas are wary of repeating the 'triumphalism' that led to a premature uprising four years ago and avoid talk of imminent revolution. And yet there are times, when you catch a companero alone cleaning up his rifle or sewing the sole back on to his boot, that he opens up and you feel a sense of renewed Optimism, a hint that maybe the revolution isn't so far away after all. He knows the army has done nothing to address the root causes of the insurgency, that though it may publish fascinating pamphlets 'about its campaign to discipline the robber barons, the worst offenders are the col- onels themselves. And he is watching as Guatemala's once sturdy economy de- 'clines, as chronic inflation, the fruit of fiscal debauchery by successive military governments, turns subdued stu- dents into wild protesters, charging through the capital burning and looting.

But he doesn't dwell on it. ORPA is fighting a 'prolonged war' and they don't want dreamers in the armed vanguard. Their strategy is slow and steady penetra- tion. Rather than slog it out with the army in a battle the guerrillas would surely lose they are building up mass support that will be ready to strike when the moment comes. 'We are going through a silent process of growth and consolidation,' says Pancho. 'Our popular base is extensive and experienced. It is not the sort of untried, enthusiastic support you get at the begin- ning of a war.'

We met some of those supporters on our way out of rebel territory. For safety we left by a different route, this time with an escort of nine combatants. It was horrific. For hours we meandered down rapids, at first hopping from rock to rock as the path crossed from one side of the river to the other, then, as torrential rain poured into the river-bed, having to wade up to our chests. By midnight it was impossible to cross. Our scout set out into the swirling waters and was thrown back onto the rocks. We couldn't risk waiting for the water to drop, so we formed a human chain, linked by rifles, and edged our way slowly across. Soaked again, we stumbled on, descending from the coffee and carda- mom fincas of the highlands to the cacao and sugar of the piamonte. There we rested with a guerrilla task force that had been camped for 28 days in the middle of a large plantation without being detected by the army. All day long, as we dozed and licked our wounds, peasants came and went with baskets of food, or with gifts of cigarettes, or just to pay a friendly call. Some spoke no Spanish and needed an interpreter but all had the same story to tell: that little had changed since their ancestors were first conquered by the Spanish and that to demand their legal rights was tantamount to subversion. Many are veterans of the resistance and, asked if they would fight when the time came, said 'Claro' — of course.

'The army only knows one way of holding back popular insurrection and that is through repression,' says Pancho, 'but the cycles are getting shorter; it is only three years since the last wave of army terrorism and already mass support is building up again. How much longer can they keep it up?' A while yet, probably; one should never underestimate genocide as a method of control.

And would it be a good thing, anyway, if the guerrillas were to bring down the whole fascist edifice? One can't help being on their side and sharing their vision of a better Guatemala, for they have yet to prove themselves unfit to rule. But the sad truth is that few of my fine friends, if any, would have much say in the revolutionary junta. Some wretched communist would come to the fore and ruin everything; some vile ideologue would steal the revolution from the Mayan peasants who wrought it; some fatuous bureaucrat would put them into collectives and rake off their profits to pay for a vast ministerium that nobody wanted. And 30 years from now another tyranny, certainly no worse, but probably little better, would be ensconced in Guate- mala.

But then maybe I'm a pessimist.

Previous page

Previous page