He should have died hereafter

Andrew Clifford

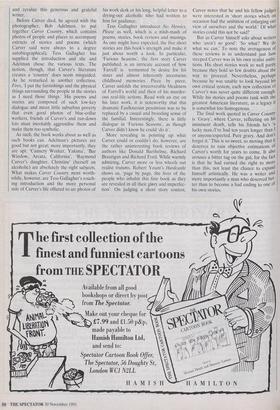

NO HEROICS PLEASE: UNCOLLECTED WRITINGS by Raymond Carver £13.99, pp. 239 CARVER COUNTRY: THE WORLD OF RAYMOND CARVER photographs by Bob Adelman, introduction by Tess Gallagher Pan, £20, pp. 160 When Raymond Carver's life was tragically cut short at the age of 50 it was as though his career had been abbreviated rather like his own sawn-off short stories. But, whereas rereading his fiction reveals a complex but eventually penetrable symbol- ism and morality, Carver's demise offers no such consolations. Here was a brilliant man who had ruined his writing career and his marriage through drink, been reborn, thanks, in great part, to the intervention of the poet Tess Gallagher, enjoyed 'five years of gradual acknowledgement' (as Gallagher puts it) which, as everyone must know, is simply nowhere near long enough; and then suddenly died of cancer. While, on the one hand, it is difficult not to have reserva- tions about both of these books as products intended for a particular literary 'market', they do at least allow us to remember

and revalue this generous and grateful writer.

Before Carver died, he agreed with the photographer, Bob Adelman, to put together Carver Country, which contains photos of people and places to accompany extracts of stories and poems (which Carver said were always to a degree autobiographical). Tess Gallagher has supplied the introduction and she and Adelman chose the various texts. The notion, though, that Carver's literature creates a 'country' does seem misguided. As he remarked in another collection, Fires, 'I put the furnishings and the physical things surrounding the people in the stories as I need those things.' His poems and stories are composed of such low-key dialogue and mean little suburban poverty that even good photos of blue-collar workers, friends of Carver's and run-down lots must inevitably aggrandise them and make them too symbolic.

As such, the book works about as well as such books can. Adelman's pictures are good but not great; more importantly, they are apt. 'Cannery Worker, Yakima', 'Bar Window, Arcata, California', 'Raymond Carver's daughter, Christine' (herself an alcoholic) are absolutely the right subjects. What makes Carver Country most worth- while, however, are Tess Gallagher's touch- ing introduction and the more personal side of Carver's life offered to us: photos of his work desk or his long, helpful letter to a drying-out alcoholic who had written to him for guidance.

Tess Gallagher introduces No Heroics, Please as well, which is a mish-mash of poems, stories, book reviews and musings. As one might have expected, the five short stories are this book's strength and make it just about worth a look. In particular, 'Furious Seasons', the first story Carver published, is an intricate account of how 'Farrell' is tormented by desire for his sister and almost inherently incestuous childhood memories. Piece by piece, Carver unfolds the irrecoverable bleakness of Farrell's world and then of his murder- ous real-life actions. Read with an eye on his later work, it is noteworthy that this dramatic Faulknerian pessimism was to be replaced by a casual and brooding sense of the familial. Interestingly, there is little dialogue in 'Furious Seasons', as though Carver didn't know he could 'do it'.

More revealing in pointing up what Carver could or couldn't do, however, are the rather uninteresting book reviews of authors like Donald Barthelme, Richard Brautigan and Richard Ford. While warmly admiring, Carver more or less wheels out realist truisms. Robert Yount's Hardcastle shows us, 'page by page, the lives of the people who inhabit this fine book as they are revealed in all their glory and imperfec- tion'. On judging a short story contest, Carver notes that he and his fellow judges were interested in 'short stories which on occasion had the ambition of enlarging our view of ourselves and the world.' Of what stories could this not be said?

But as Carver himself asks about writers who 'aren't so good': 'So what? We do what we can.' To note the averageness of these reviews is to understand just how steeped Carver was in his own realist ambi- tions. His short stories work so well partly because they hold so few doubts about the way to proceed. Nevertheless, perhaps because he was unable to look beyond his own critical system, each new collection of Carver's was never quite different enough. While his stories and poems rank with the greatest American literature, as a legacy it is somewhat too homogenous.

The final work quoted in Carver Country is 'Gravy', where Carver, reflecting on his imminent death, tells his friends he's 'a lucky man./I've had ten years longer than I or anyone/expected. Pure gravy. And don't forget it.' This is so sweet, so moving that it deserves to ruin objective estimations of Carver's worth for years to come. It also arouses a bitter tug on the gut, for the fact is that he had earned the right to more than this, not least the chance to expand himself artistically. He was a writer and more importantly a man who deserved bet- ter than to become a bad ending to one of his own stories.

Previous page

Previous page