Architecture

Hopkins and historicism

Alan Powers on the refurbishment of Bracken House Then the building got listed,' said Michael Hopkins, architect of the nearly Completed additions to Bracken House, speaking recently at the Royal Society of Arts. Before the listing, Michael Hopkins and Partners had prepared a redevelop- ment scheme for the Obayashi Corpora- tion, the new owners of Bracken House, Sir Albert Richardson's 1959 classical com- mercial palace, built for the Financial Times. As Sir Nikolaus Pevsner said, it would have been modern in 1910. In 1988 it became the first post-1939 building in Britain to be listed.

Michael Hopkins is associated with the high tech movement in British architecture. He started his practice in 1976 after work- ing with Foster Associates, and was imme- diately famous for his well-groomed minimalist house in Downshire Hill, Hampstead. High tech presents itself as a rational, lightweight architecture led by technology, deriving its genealogy from the American theorist-designer Buckminster Fuller and, further back, the functional tra- dition of 19th-century industrial buildings.

House first scheme for Bracken

rlouse was an extremely interesting one, With load-bearing brick walls and cast-iron girders, more closely related to a Victorian Warehouse than a Miesian shed. He called it 'my campaign against curtain walling'. Some architects in this situation might have 'ought against the listing, but the clients were evidently prepared to play by the rules and, instead of cultivating the 'sod You' attitude, Hopkins, after further ,thought and research, came up with a bril- liant solution to adapting Bracken House, based on an alternative realisation of one of Richardson's sources for this island site, the 1680s Palazzo Carignano in Turin by uuarini. The north and south ranges remain externally unaltered, while the cen- tre, originally the printing works, has been _replaced by a completely new structure. The stone bases from which Hopkins's cast-iron bays spring are solid, not faced-up

concrete. Radiating concrete beams are vis- ible in the ceilings. The integrity of the new construction enhances Richardson's design and the old professor, sworn enemy of modernism, might believe that his building has taught a valuable lesson.

In his RSA lecture, 'Technology Comes to Town', Michael Hopkins hardly had a good word to say for Richardson's building, and gave the impression of resenting this shotgun marriage. At least one critic has berated him for selling out to 'heritage' in the series of designs involving the conflict- ing interests of abstract modernism and specific sites, starting with the Mound Stand at Lords of 1987, which were the subject of the lecture. The justice or injus- tice of such accusations touches on some of the issues that make British architecture today such a battleground.

These projects are popular and unthreat- ening. Showing construction and materials for what they are, a commonplace of mod- ernism seldom strictly observed, they have integrity without arrogance. The abolition of the load-bearing external wall was one of modernism's supposedly greatest achievements, but Hopkins has brought it back as the focus of interest. At Bracken House, he didn't want to express the struc- ture like the Lloyd's building, but to explore the use of the outside wall to hold the building up, 'and hopefully some char- acter will result'. In his David Mellor shop and office building at Butler's Wharf and the earlier circular factory for David Mel- lor at Hathersage, the client's understand- ing of the potential exchange between architecture and the crafts has proved high- ly creative and has virtually established a new architectural genre.

Like nearly all architects now working in Britain, Michael Hopkins understands modern architecture as a progressive force formed by the conditions of modern life. The works in which he has brought tech-

nology to town have shown that the conflict between an old city environment and the imperatives of new technology can be resolved not merely by compromise, but in the production of architecture of the high- est quality — there is no sell-out. If one is aware of the existence of a conflict, it is because of a belief that architecture con- sists of styles specific to certain periods, each age being clearly separate. This is an extension of one of the philosophical falla- cies exposed in Sir Karl Popper's The Poverty of Historicism in 1944. 'The poverty of historicism', wrote Popper, 'is a poverty of imagination.' It was a method of inter- preting the past which was not necessarily completely wrong, merely inadequate and limited.

In architecture, the word historicism is usually taken to mean something almost opposite: the design of buildings with refer- ences to the past, something Richardson did willingly at Bracken House. The con- tradictory meanings were pointed out by David Watkin in Morality and Architecture (1977), using Popper's text to reveal the influence of Pevsner's historicism [first meaning] in trying to suppress historicism [second meaning]. Buildings like Bracken House presented Pevsner with a problem. He could not help a sneaking admiration for them, but his inability to fit them into his theoretical scheme forced him to deny it.

Watkin's book indicates no specific architectural style, asserting instead the freedom of the individual architect to make choices. Architectural thinking is still domi- nated by historicism [first meaning], whether it is used to support 'traditionalist', 'post-modernist' or 'neo-modernist' styles. It is one of the most destructive ideologies, and Popper rightly identified its stultifying effect on imagination. In Michael Hop- kins's buildings freedom of imagination has put ideology in second place.

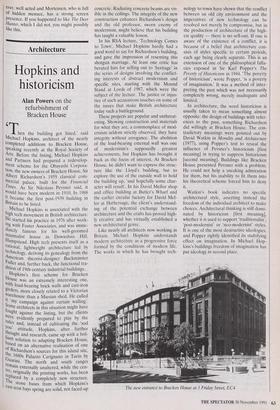

The new entrance to Bracken House at 1 Friday Street, EC4

Previous page

Previous page