The Ultimatum

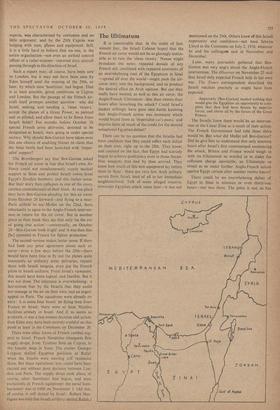

It is conceivable that, in the midst of last- minute fear, the Israeli Cabinet hoped that the French air cover would not be so glaringly notice- able as to ruin the 'clean victory.' Nasser might broadcast the news; repeated denials of any French aid, combined with repeated assertions of an overwhelming rout of the Egyptians in Sinai —spread all over the world—might push the air- cover story into the background, and so produce the desired effect on Arab opinion. But can they really have wanted, as well as this air cover, the Anglo-French Ultimatum—less than twenty-four hours after launching the attack? Could Israel's leaders willingly have gone into battle knowing that Anglo-French action was imminent which would brand them as 'imperialist cat's-paws,' and deprive them of much of the credit for the desired sensational Egyptian defeat?

There can be no question that the Israelis had been confident that they could inflict such defeat on their own, right up to the 28th. They knew, and counted on the fact, that Egypt had scarcely begun to achieve proficiency even in those Soviet- bloc weapons that had by then arrived. They knew how much of this new equipment lay before them in Sinai : there are very few Arab military secrets from Israel, least of all in her immediate neighbourhood. Talk of some alleged massive, imminent Egyptian attack came later—it was not mentioned on the 29th. Others knew of this Israeli superiority and confidence—not least Selwyn Lloyd in the Commons on July 2, 1956, whatever he and his colleagues said in November and December.

Later, many journalists gathered that Ben- Gurion was very angry about the Anglo-French intervention. The Observer on November 25 said that Israel only expected French help in her own war. The Times correspondent described the Israeli reaction precisely as might have been expected :

Apparently [Ben-Gut-ion] wanted nothing that would give the Egyptians an opportunity to com- plain that they had been beaten by superior forces, and above all by the forces of the Great Powers.

The Israelis knew there would be an interven- tion in the Canal Zone as a result of their action. The French Government had told them there would be. But who! did Mollet tell Ben-Gurion? Did he give him to understand that only nineteen hours after Israel's first communiqué announcing the attack, Britain and France would weigh in with an Ultimatum so worded as to make the collusion charge inevitable; an Ultimatum so timed as to make further Anglo-French action against Egypt certain after another twelve hours?

There could be no overwhelming defeat of Egypt in Sinai in nineteen or even thirty-one hours--nor was there. The point is not, as has

been argued, that the Israelis knew Egypt would reject the Ultimatum, thereby giving them more time to inflict their defeat. The point is that it ceased to be a purely Egyptian-Israeli battle too Soon for the Israelis to prove themselves the vic- tors. British bombers arrived too soon. And the Anglo-French Ultimatum, coming when it did and as it did, made it possible for President Eisen- hower to weigh in as strongly as he wished against Israel. If the Israelis thought that an American President fighting an election campaign would find it difficult to condemn them they were, in any case, Wrong. But within hours of Eisenhower going to the Security Council, London and Paris had handed him any extra help he needed to save him from possible electoral embarrassment.

Previous page

Previous page