xploding the myth

If Chernobyl is the worst-case scen we've got nothing to worry about

It was a disaster of biblical proportions. Any European older than about 30 can probably remember where they were when Chernobyl blew. On 26 April 1986, a chemical explosion at Reactor No. 4 led to an uncontrolled graphite fire at the reactor core. A 1,000-tonne shield was blasted into the air releasing a cocktail of radio-isotopes into the surrounding area, and a blast of ionising radiation made the air flash blue around the stricken plant.

After days of neo-Stalinist obfuscation, the authorities acted. More than 200,000 people were evacuated, and soon tales of radiation-generated carnage emerged. Several people were killed by the explosion itself, hut of course the real danger

lay in the dusting of deadly radionuclides most notably iodine-131 and caesium-137 — which rained down upon parts of Belarus and Ukraine. Prevailing winds carried this radioactive cocktail north and west, where it rained down on Lapp, Welsh and Cumbrian hillsides. Chernobyl was, by far, the world's worst ever nuclear accident, a perpetual thorn in the nuclear industry's side. The word `chernobyl' apparently translates as 'wormwood', the bitter herb of Revelation — a spooky coincidence not lost on those of a fundamentalist bent.

The sheer horror and magnitude of the Chernobyl disaster

is surely beyond dispute. So it seems pointless tasteless, even — to ask just how bad it really was. But do a bit of scratching around, and you soon learn that rio incident in history has been so surrounded by lies, myths and misconception.

The first myth is that Chernobyl killed hundreds of thousands of people. One Ukrainian victims' group has claimed that 150,000 people were killed by the disaster. The Ministry of Public Health in that country quoted a figure of some 125,000 in April 1995. But as time wore on, these fig ures were revised downwards, although they still remained high, By the mid-1990s, however, the 'accepted' number of deaths was usually in the 10,000-20,000 range, with figures of more than 32,000 being quoted regularly by broadcasting organisations, other media and, especially, environmentalist groups. In 2000, the BBC was still reporting, uncritically, that Chernobyl had left 15,000 dead and 50,000 crippled by radiation.

The second myth is that Chernobyl unleashed a wave of disease, particularly cancers and birth defects, across the region. We all remember seeing the 'Children of Chernobyl', pitiful leukaemia sufferers brought to the West to recuperate by various charities. And the legacy of Chernobyl goes, we are told, far beyond its impact on lives and health. The area in which the stricken reactor is located is a vast 'dead zone' which will be uninhabitable for centuries, where the ground crackles with radiation.

Refuting these myths is quite easy. In fact, 31 people were killed when the reactor blew — 28 from radiation exposure and three scalded by escaping steam. An additional 134 people received high radiation doses and 14 have subsequently died, although several of unrelated causes. A United Nations report on the tragedy concluded that the radiation from Chernobyl caused absolutely no measurable increase whatsoever in birth defects and — amazingly — no increase in the 'background rate' of leukaemia. In fact, the only long-term effect of the release of radiation has been a modest increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer in children horn before the accident.

One of the most definitive studies to date of the incidence of thyroid cancer post-Chernobyl has been carried out by Professor Philip Thomas, an expert in risk assessment at City university. He has found that some 1,750 cases of this disease could probably he attributed to the accident up to 1998. 'Not all these victims should die,' he points out. In fact, thyroid cancer is eminently treatable and 95 per cent of victims go into full remission. Nevertheless, this is a poor part of the world so assuming that many of the victims will not have been given the surgery and drug treatment they would receive in the West, Professor h T . -MIMS estimates that maybe 1,000 deaths in total will result from the accident (including those killed initially byblast and radiation).

Still, 1,000 deaths is pretty bail. But how does it compare with other man-made disasters? And specifically, what does Chernobyl teach us about the relative safety of atomic power compared with other means of electricity generation?

The fact that Chernobyl was by far the world's worst nuclear accident tells us just how safe nuclear power is. A recent study carried out by the Paul Seherrer Institute in Switzerland, a physics research Organisation, attempted to quantify the relative risks of various types of electricity generation. The results, the most definitive study to date, make interesting reading.

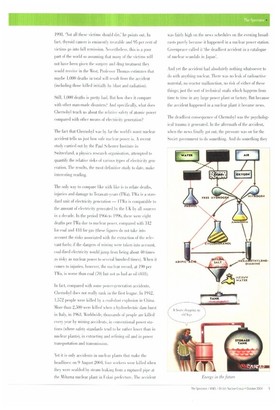

The only way to compare like with like is to relate deaths, injuries and damage to Terawatt-years (TWa). TWa is a standard unit of electricity generation — ITWa is comparable to the amount of electricity generated by the UK by all sources in a decade. in the period 1966 to 1996, there were eight deaths per TWa due to nuclear power, compared with 342 for coal and 418 for gas (these figures do not take into account the risks associated with the extraction of the relevant fuels; if the dangers of mining were taken into account, coal-fired electricity would jump from being about 40 times as risky as nuclear power to several hundred times). When it comes to injuries, however, the nuclear record, at 190 per TWa, is worse than coal (70) but not as bad as oil (441).

Lit fact, compared with some power-generation accidents, Chernobyl does not really rank in the first league. In 1942, 1,572 people were killed by a coal-dust explosion in China. More than 2,500 were killed when a hydroelectric dam burst in Italy, in 1963. Worldwide, thousands of people are killed every year by mining accidents, in conventional power stations (where safety standards tend to he rather lower than in nuclear plants), in extracting and refining oil and in power transportation and transmission.

Yet it is only accidents in nuclear plants that make the headlines; on 9 August 2004. four workers were killed when they were scalded by steam leaking from a ruptured pipe at the Mihama nuclear plant in Fukui prefecture. The accident was fairly high on the news schedules on the evening broadcasts purely because it happened in a nuclear power station. Greenpeace called it the deadliest accident in a catalogue of nuclear scandals in Japan'.

And yet the accident had absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with anything nuclear. There was no leak of radioactive material, no reactor malfunction, no risk of either of these things; just the sort of technical snafu which happens front time to time in any large power plant or factory. But because the accident happened in a nuclear plant it became news.

The deadliest consequence of Chernobyl was the psychological trauma it generated. In the aftermath of the accident, when the news finally got out, the pressure was on for the Soviet government to do something. And do something they

did. Hundreds of thousands of people were evacuated from the area. Towns such as Pripyat became ghost towns almost overnight.

The forcible relocation of so many terrified citizens took a terrible toll. Men and women lost their jobs; children were taken out of school. Networks of families and friends were shattered. The USSR of the late-1980s was not an affluent society. The sorts of support networks, professional counselling and psychiatric monitoring that we would take for granted in the West simply weren't there, Thousands — perhaps tens of thousands — turned to drink. Marriages collapsed, teenagers turned to drugs. Everyone smoked more. and health consciousness dropped to zero. The stress, the unhealthy lifestyles and the nightmarish disruption took their toll. Thousands did die, but not of radiation. Instead. the real victims of Chernobyl were felled by heart attacks, strokes and suicide. More than 50,000 local women had abortions, convinced their unborn children would be born deformed. Paradoxically, if the Kremlin had stood its ground, kept shtoom and made everyone stay put, the scale of the disaster would have been much reduced.

Chernobyl did not kill thousands of people, nor did it contaminate huge areas of land for centuries, as is commonly believed. Today, radiation levels in the area, while still above the ideal minimum, have mostly fallen to well below the natural background levels found in places such as south-west France and sonic parts of Britain where there is radioactive granite. Chernobyl left no legacy of birth defects. nor are there thousands of cancer sufferers all over Europe who can attribute their disease to this badly designed and mismanaged power station.

The final, and strangest, myth of all is that this truly was a biblical tragedy. The trouble is that 'clierriobyr does not actually translate as 'wormwood' (Artemesia absinthium), with its consequent apocalyptic connotations, at all. In fact. it means mugworr (Ariemesin rulgaris), a related but differ em herb. Close enough for myth, but no cigar.

There are some sound arguments against nuclear power. We still have not evaluated all the risks. The fact that plants could take decades to decommission safely means that we are, to an extent, gambling with our future. But Chernobyl, in itself, is not an argument for anything other than the sheer power of modern mythmaking. Et worked then, it worked in Hiroshima and in Nagasaki, and it works now in nuclear power stations worldwide. Whether it is used to destroy cities or to run them, the power unlocked by carving up the atom is created the same way.

The secret of nuclear power is that atoms split themselves. The nuclei of the atoms that make up elements like plutonium or uranium are so heavy that they fall apart on their own, releasing subatomic particles called neutrons. Everyradioactive nucleus has a characteristic rate at which it happens — some fast, some slow. Plutonium, for instance, releases neutrons so quickly that if you hold a sample of it in your hand it will be warm to the touch. The trick to making an A-bomb like the one detonated at Los Alamos, or a nuclear reactor like those designed and decommissioned by BNFL, is to get radioactive atoms to release their neutrons at just the right speed so that they are absorbed by the nucleus of another atom. This swollen nucleus will then split even sooner than the old one, releasing its own neutron into the nucleus of another atom and so on, creating the chain reaction which makes nuclear power.

Previous page

Previous page