The Final Design

Writing about the town for the Architectural lorrnrai Gibberd gave a motorist's-eye view of the town From them [the main roads] a series of Pictures of the town are seen in rapid sequence, and these pictures may be heightened and dramatised by siting the roads with a vieW to the different building groups and landscape compositions which will burst into view.' It is 190 early to pass final judgments on views of this kind, partly because building is nowhere near complete, partly because some of the land- scaping schemes will take twenty years to mature, partly because expediency may encourage build- Irng In Places where the Master Plan had hoped for trees or woods or parkland. But there are !DaLrts of the town where one already gets an Writing about the town for the Architectural lorrnrai Gibberd gave a motorist's-eye view of the town From them [the main roads] a series of Pictures of the town are seen in rapid sequence, and these pictures may be heightened and dramatised by siting the roads with a vieW to the different building groups and landscape compositions which will burst into view.' It is 190 early to pass final judgments on views of this kind, partly because building is nowhere near complete, partly because some of the land- scaping schemes will take twenty years to mature, partly because expediency may encourage build- Irng In Places where the Master Plan had hoped for trees or woods or parkland. But there are !DaLrts of the town where one already gets an the nobility of the final design. Every acre is turned to good account either for Pure utility, or for recreation, or for offering Something pleasant to look at. Like all tidiness the way to lay out a town economically is to pnt beauty first, or anyhow well up on the list N Priorities. It may produce some extravagances the visiting Chief Architect of Moscow was shocked d that First Avenue did not describe a straight line—but in the end it 'is probably no amore to respect an existing landscape, Gibberd has done, to keep as many of its awoods, Ponds, trees, hedges and grassy banks rate everything, start building from scratch, and then try to inject a little artificial 'landscape' into it afterwards, as happened in the housing estates of the Thirties.

The scale of his work at Harlow quickly began to teach Gibberd new ways of thinking about architecture. Like most architects he had thought previously in terms of 'internal space.' This meant that one thought about the inside of a building first and the outside followed logically from the shape of the inside. But Harlow taught him 'to look at this idea in a new way, really to turn it inside out. The conception of the 'enclosed space' could be applied to streets and squares as well as to rooms. The shop-fronts of a shopping street formed in effect a long, narrow room; the buildings round a square made the walls of a wide, airy one. But if this idea was going to work it meant that the architects involved must• design not just buildings here and there, but a whole square, or a set of streets, or a complete parade of shops, together with all the roads that led to them. The old system still practised all over the country, under which a municipal engin- eer built the roads and an architect, or more probably a builder, simply planted houses along the edges of them, would not do for Harlow. The Architect-Planner would decide, with the approval of the Corporation Board, where squares, shopping streets, or housing areas would be. The squares, shops and houses would be built with the utmost respect for natural beauty and with the idea of giving people the nicest possible setting in which to live. Then the roads would be brought to the buildings.

The idea of the 'enclosed space' was to take on a life of its own as Harlow developed, and in recent years Gibberd has started talking about `precinctual building'—a more positive way of describing the same thing. The precinct idea gives

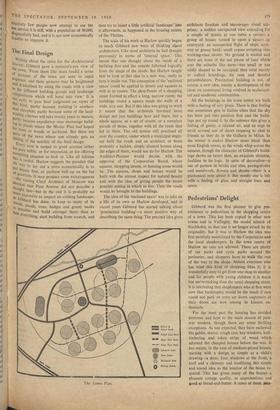

The Town Plan.

architects freedom and encourages visual sur- prises: a sudden unexpected view extending for a couple of streets as one turns a corner; a group of houses turned in upon a square or courtyard; an unexpected flight of steps, arch- way or grassy bank; small copses errupting into working-class streets. No ground is wasted and there are none of the sad pieces of land which scar the suburbs like sores—too small or too oddly shaped to be occupied, they exist merely to collect hoardings, tin cans and derelict perambulators. Precinctual building is not, of course, a new idea, merely a development of the ideas on communal living evolved in ecclesiasti- cal and academic communities.

All the buildings in the town centre arc built with a feeling of airy grace. There is that feeling one sometimes gets in Italian cities that the sky has been put into position first and the build- ings put up round it. In the summer this gives a feeling of gaiety, a relaxed air, and an urge to stroll around out of doors stopping to chat to friends as they do in the Galleria in Milan. In the winter it makes Harlow more bleak than most English towns, as the winds whip across the squares, though the character of Gibberd's build- ings shows up better then, an exquisite skeleton, faultless in its logic. In spite of decoration—a use of pattern in bricks and tiles, paving-stones and metalwork, flowers and shrubs—there is a puritanical note about it. But mostly one is left with a feeling of glass and straight lines and space.

Previous page

Previous page