On Brendan and Noel

Kenneth Hurren

Intensive ransacking of the annals of the theatre might just conceivably yield a brace of talents more dissimilar than those that produced the two principal new shows in London last week, but they certainly don't occur to me offhand. Noel Coward's Private Lives, written in 1930 and now glossily revived at the Queen's, is wilfully artificial; its characters, though bearing passing resemblances to human beings, have no visible means of support and are people created essentially, indeed exclusively, to inhabit the situation of the play, outside the confines of which it is hardly possible to believe in their existence, let alone to imagine their activities; but for the period of the play, disbelief is suspended, as they say, and their engaging capers — seemingly so casual and carefree — are organised with fastidious care, symmetry and, of course, ineffable sophistication. Coward's flair for such things, arduously cultivated and painstakingly disciplined, is the antithesis of everything that the late Brendan Behan brought to the theatre, and Richard's Cork Leg — posthumously attributed to him and, offered at the Royal Court, following its premiere at the Dublin Festival earlier this year — is belligerently ill-organised, and roughly as disciplined, symmetrical, fastidious and sophisticated as a boozy night in the bars of Dun Laoghaire. It really has no particular business on the professional stage, but for all the waywardness it is entertaining as often as it is exasperating, and there are vagrant ideas in it that might have come to something if Behan had had the application — not to mention the sobriety — to get to grips with them.

I can myself get to grips more quickly with Private Lives, if only because there can be few playgoers who will require much information about its plot which, in any case, is remarkably meagre. It seems hardly necessary to say more than that this is the comedy set in motion by the whopping coincidence of the presence at Deauville — in hotel rooms with adjoining balconies — of a man and woman formerly wedded to each other but now on honeymoon with new spouses. Even those who will be seeing the piece for the first time — doubtless a negligible minority — are unlikely to be biting their nails in the suspense of wondering what will happen: everything is clear from the moment Elyot and Amanda confront each other with consternation and appropriate doubleAakes as the off-stage band plays 'their song.' Living together they may react as explosively as nitric acid and glycerine, but it is clearly impossible for them to live apart. The recognition of this little central truth and the mechanics of disentanglement from their newly acquired, partners are spread over a couple of hours or so in as deft an exercise in high comedy fashioned from candy floss as the theatre of this century has known.

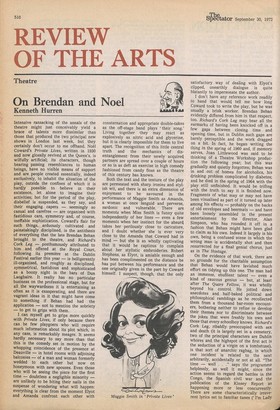

Both the text and the texture of the play are permeated with sharp ironies and stylish wit, and there is an extra dimension of enjoyment to be savoured in the performance of Maggie Smith as Amanda, a woman at once languid and perverse, sardonic and vulnerable. There are moments when Miss Smith is funny quite independently of her lines — even a few moments when her instinct for the absurd takes her perilously close to caricature, and I doubt whether she is ever very close to the Amanda that Coward had in mind — but she is so wholly captivating that it would be captious to complain about her stylistic embroideries. Robert Stephens, as Elyot, is amiable enough and has been complimented on the distance he has put between his performance and the one originally given in the part by Coward himself. I suspect, though, that the only satisfactory way of dealing with Elyot's clipped, unearthly dialogue is quite blatantly to impersonate the author.

I don't have any reference work readily to hand that would tell me how long Coward took to write the play, but he was usually a brisk worker. Brendan Behan evidently differed from him in that respect, too. Richard's Cork Leg may bear all the earmarks of having been knocked off in a few gaps between closing time and opening time, but in Dublin such gaps are barely perceptible and the work dragged on a bit. In fact, he began writing the thing in the spring of 1960 and, if memory serves, Joan Littlewood was said to be thinking of a Theatre Workshop production the following year; but this was gradually and quietly forgotten; Behan was in and out of homes for alcoholics, his drinking problem complicated by diabetes; and he died in the spring of 1964 with the play still unfinished. It would be trifling with the truth to say it is finished now. Fragments of what may or may not have been visualised as part of it turned up later among his effects — probably on the backs of old envelopes and beermats — and have been loosely assembled in the present entertainment by the director, Alan Simpson, who has rounded it off in a fashion that Behan might have been glad to claim as his own. Indeed it largely is his own, being a confused scene in which the wrong man is accidentally shot and then resurrected for a final genial chorus, just as in The Hostage, On the evidence of that work, there are no grounds for the charitable assumption that Behan would have lavished much effort on tidying up this one. The man had an immense, ebullient talent — even a kind of raucous genius — but, at least after The Quare Fellow, it was wholly beyond his control. He jotted down anecdotes and half-baked political and philosophical ramblings as he recollected them from a thousand bar-room encounters, bothering neither to refine or develop their themes nor to discriminate between the jokes that were freshly his own and those that every schoolboy knows. Richard's Cork Leg, ribaldly preoccupied with sex and death (it is largely set in a cemetery, two of the principal characters are Dublin whores and the highspot of the first act is the seduction of a virgin on a tombstone), is that sort of anarchic ragbag, in which one incident is related to the next arbitrarily, accidentally or not at all. "The time — well . . ." says the programme helplessly, as well it might, since the action seems to regard the battles in the Congo, the Spanish civil war and the publication of the Kinsey Report as

happening more or less concurrently. There are some characteristically irreverent lyrics set to familiar tunes (' I'm Lady

Chatterley's Lover' to the tune of ' Land of Hope and Glory' is one of them) and buoyantly rendered by The Dubliners. "It gets better as we go along," says someone bravely. Promises, promises. But the participants are unremittingly enthusiastic, and sporadically their cheerfulness is astonishingly infectious.

Previous page

Previous page