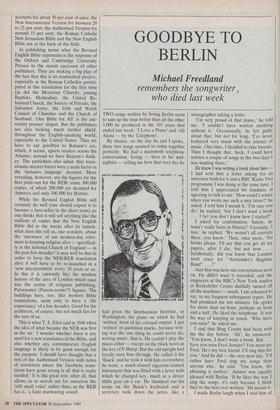

GOODBYE TO BERLIN

Michael Freedland remembers the songwriter, who died last week

TWO songs written by Irving Berlin seem to sum up the man better than all the other 3,000 he produced in the 101 years that ended last week: 'I Love a Piano' and 'All Alone — by the Telephone'.

By chance, on the day he and I spoke, those two songs seemed to come together perfectly. We had a mammoth telephone conversation, Irving — then in his mid- eighties — telling me how that very day he had given the Smithsonian Institute, in Washington, the piano on which he had 'written' most of his colossal output. I put `written' in quotation marks, because writ- ing was the one thing he could never do; writing music, that is. He couldn't play the piano either — except on the black notes in the key of F-Sharp. But the old upright had loyally seen him through. He called it his 'Buick' and he took it with him everywhere he went, a much-abused cigarette-stained instrument that was fitted with a lever with which he changed key, much as a driver shifts gear on a car. He thumped out his songs on the Buick's keyboard and a secretary took down the notes, like a stenographer taking a letter. 'I'm very proud of that piano,' he told me. 'I couldn't have written anything without it.' Occasionally, he felt guilty about that, but not for long. 'I've never bothered very much with the science of music. One time, I decided to take lessons. Then I thought that, heck, I could have written a couple of songs in the two days I was wasting there.'

He knew I was writing a book about him I had sent him a letter asking for an interview both for it and a BBC Radio Two programme I was doing at the same time. I told him I appreciated his kindness in agreeing to talk to me. 'How could I refuse when you wrote me such a nice letter?' he asked. I told him I meant it. 'I'm sure you do,' he replied, 'but I don't want a book . . . I bet you don't know how I started?'

I asked for confirmation. Surely, he wasn't really born in Siberia? 'Certainly, I was,' he replied. 'We weren't all convicts there, you know.' Then, once more, 'No books please. I'll see that you get all my papers, after I die, but not now . • • • Incidentally, did you know that London went crazy for "Alexander's Ragtime Band" . . .?'

And that was how our conversation went on. He didn't want it recorded, and the engineers at the BBC's New York studios at Rockefeller Center dutifully turned off all the machines — much, I am ashamed to say, to my frequent subsequent regret. He had promised me ten minutes. He spoke for more than an hour, perhaps an hour and a half. He liked the telephone. It was his way of keeping in touch. 'Who have you seen?' he asked me.

I said that Bing Crosby had been with me the day before. `Ah', he answered. 'You know, I don't want a book. But . . • have you seen Fred Astaire? You must see Fred. He's my best friend. I'll ring him for you.' And he did — the very next day. 'I'd rather have Fred sing my songs than anyone else,' he said. 'You know, his phrasing is perfect.' Astaire was equally pleased with Berlin. 'If he likes the way I sing the songs, it's only because I think they're the best ever written.' He meant it. I made Berlin laugh when I told him of Crosby's recollections of first hearing `White Christmas'. Berlin had played the piece, looking as anxious as if he had just been wheeled out of the intensive care ward. 'I don't think you need worry about that one,' said Bing. What Berlin worried about was that someone else could be making money that should have been his. Crosby told me that the director of the film `Holiday Inn', Mark Sandrich, planned to fade out a scene on one long note. 'One of my notes . . ,?' Berlin asked. It is not a surprising question from the man who always had a prohibition against parody on printed copies of his music and could read a balance sheet better than a song sheet.

Occasionally, in our conversations, he feigned modesty. 'Let me tell you some- thing about songwriters and their figures,' he said. 'A song becomes a hit and sells perhaps 7,500 copies. To the songwriter, that's always two million. But the figures for "White Christmas" are really very impressive.' The latest 'White Christmas' figures are impressive to the tune of 300 million.

As a five-year-old, I bad been taken to see his all-soldier show This is the Army at the London Palladium. From the balcony I saw him in his ill-fitting first world war uniform, complete with the Boy Scout-type hat on his head, singing 'Oh, How I Hate to Get up in the Morning.' I knew then what it was like to put real emotion into a song.

'Oh, yeh,' he said, 'I know what you mean. But that's just what I do. I wrote "Oh How 1 Hate to Get up in the Morning" because I really do like to sleep late.'

'You're not writing a book, are you? . . But I bet you didn't know that it was Lady Edwina Mountbatten who got that show going for me in London. She persuaded Churchill to lift paper rationing so that we could print copies of my song, "My British Buddy".'

We talked about songs of the day. The big hit then was called 'Little Green Apples', which contained the line, 'God didn't make little green apples, and it don't show in Minneapolis.' He liked that tune. 'But,' he told me, 'I'd never have written it that way. I'd have said, 'God didn't make little green apples and we don't pray in churches and chapels . . • •' What was safe to discuss was his then new occupation — painting pictures that he had sent to Fred Astaire of birds wearing top hats, signing them 'Izzy' or sometimes 'Vincent'. He never painted, them with feet. 'I can't paint feet,' he said. 'As a Painter, I'm a pretty good songwriter.' As a songwriter, he was a pretty good song- writer, too. I told him I was going to write that — and for once he didn't pretend he wanted to stop me.

Michael Freedland's biography A Salute to Irving Berling is published by W. A. Allen at £11.95.

Previous page

Previous page