THE ODD THING ABOUT THE COLONEL

`A fruit machine?' enquired the of his first infantry colonel.

UPON the gentlemanly, egg-like features of my first infantry colonel had settled a more or less permanent look of mild' astonishment or bafflement. His waking life was full of little surprises, mostly disagreeable, which he greeted with comp- osure or, at worst, restrained vexation. His temper, often tested, was normally equ- able. He had a rich, fruity, throaty, garg- ling voice, like Harold Macmillan's or Julian Amery's, emerging, as it were, hollow but crisp from the bottom of a deep well. This distinguished sound was often deployed to pronounce people or events, even of quite a humdrum kind, to be `strange' or 'strange indeed', 'odd' or even `very odd'. When he referred to our own regiment, which he often did with pride, he never abbreviated its full title, never omit- ted the sonorous opening 'Royal', and would have died rather than substitute, as the irreverent often did, the word 'scruffy'. The term 'line mob' shocked him. It was as if tradition itself had spoken in him: the unquestionable arbiter of what was strange or odd and what was not.

Certainly he was not scruffy himself, though his chic was rather of the first world war, in which he had won an MC, than the second. One half expected him to carry his badges of rank on his cuffs, to refer to `whizzbangs' and 'flamin' onions', to com- mend the comforting effects on cold nights at the front of Epps's Cocoa or Dunhill's V. 0. Whisky. The silly fore-and-aft forage cap of 1939-45 did not suit him. He wisely preferred his glamorously battered and mis-shapen felt peaked cap, in the top of

which was said to be concealed the full order for battalion parade, to be consulted if memory failed. His darkly gleaming old Sam Browne had a whistle attached to it, a memento of our role as mounted infantry in the Boer War.

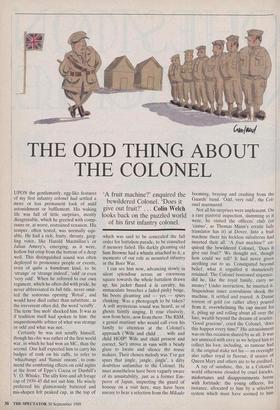

I can see him now, advancing slowly in silent splendour across an enormous square towards the whole battalion drawn up, his jacket flared a la cavalry, his immaculate breeches a faded pinky beige, his boots gleaming and — yes — spurs clanking. Was a photograph to be taken? A soft mysterious sound was heard, as of ghosts faintly singing. It rose elusively, now from here, now from there. The RSM, a genial martinet who would call even his family to attention at the Colonel's approach (`Wife and child . . . wife and child HOIP! Wife and child present and correct, Sir!) strove in vain with a beady glare to locate and silence the music makers. Their chosen melody was 'I've got spurs that jingle, jangle, jingle', a ditty doubtless unfamiliar to the Colonel. He must nonetheless have been vaguely aware of its unsuitability, just as a former Em- peror of Japan, inspecting the guard of honour on a visit here, may have been uneasy to hear a selection from the Mikado

booming, braying and crashing from the Guards' band. 'Odd, very odd', the Col- onel murmured.

Not all his surprises were unpleasant. On a rare pastoral inspection, slumming as it were, he visited the officers' club (or `casino', as Thomas Mann's erratic lady translator has it) at Dover. Into a fruit machine there his feckless subalterns had inserted their all. 'A fruit machine?' en- quired the bewildered Colonel, 'Does it give out fruit?' We thought not, though how could we tell? It had never given anything out to us. Constipated beyond belief, what it engulfed it shamelessly retained. The Colonel borrowed sixpence: did he, like the royal family, carry no money? Under instruction, he inserted it. Stupendous inner convulsions shook the machine. It settled and roared. A Danae torrent of gold (or rather alloy) poured from it, overwhelming the cup meant for it, piling up and rolling about all over the lino, wealth beyond the dreams of avarice. `Good gracious', cried the Colonel, 'does this happen every time?' His astonishment was on this occasion shared by us all. It was not unmixed with envy as we helped him to collect his loot, including, so rumour had it, the original stake not his — an oversight also rather royal in flavour, if stories of Queen Mary and others are to be credited.

A ray of sunshine, this, in a Colonel's world otherwise clouded by cruel knocks, misfortunes and disappointments borne with fortitude: the young officers, for instance, allocated to him by a selection system which must have seemed to him

perverse indeed — yes, me for a start. Yet, though no answer to any colonel's prayer, I caused him little distress that I am aware of. My smart creamy shirts caused him no pain; nor did the poetry which I then modishly read in bulk, a practice endorsed by no less an authority than Lord Wavell. Inefficiency and eccentricity were not pro- foundly distasteful to him, provided they didn't eat their peas with a knife or belch and say 'pardon, sir' or make mock of him or set fire to his Times while he read it.

On one such incendiary occasion, he cast the blazing organ aside with an oath straight into the waste paper basket. The resultant conflagration was in fact swiftly extinguished by the mess waiter with a soda syphon, but dense clouds of smoke rose and billowed up the stairs, as did the Colonel himself, spurred on by humorous- ly exaggerated screams of, 'Fire, fire!' and, `Run for your lives, gentlemen.' The Col- onel's reaction was if anything too swift.

I lost my own pistol rather early on — not that I could have hit a gasometer with it, even from inside.

He hurled all his precious possessions out of his bedroom window, where many of them stuck in a bare silver birch outside. The next morning it looked like a very grand Christmas tree, decked out with the booty of Bond Street and Jermyn Street things like exotic dressing gowns, ivory- backed brushes, silk pyjamas, bespoke shirts and boots on trees, Floris hair water, silver hip flasks in leather cases and other splendours beyond our means or even our knowledge. The Colonel was himself a bit shame-faced, but we rated him a proper toff.

More than acceptable initially to the Colonel was a very smart young officer, darkly handsome, called something exotic like Palaeologos or Thurn and Taxis, posted to us from Intelligence. Unfortu- nately this paragon had an overmastering sense of humour. One evening after dinner there were four of us in the mess, the paragon and I, the Colonel and his guest, a brigadier. The Colonel was telling a long, rambling anecdote about a hunt he had ridden to in Ulster, a very strange hunt, it seemed, with all the hounds of different sizes and breeds and many other marks of eccentricity, all lovingly recalled at length, together with confusing incidents illustra- tive of Hibernian oddity. The brigadier listened for the most part with polite attention, smiling or chuckling quietly at appropriate moments, waking with a start from little post-prandial dozes. The effect on the paragon was more disquieting. His face was completely hidden by the upheld Times, which shook alarmingly in his hands. From behind it came sounds of

irrepressible mirth: chokings, gurglings, whinnies and violent explosions. Some- thing was going wrong. The Colonel's yarn was designed to please and amuse, but not to any such disproportionate extent. Final- ly the paragon lost control, abandoned all pretence, fled from the mess, shrieking and roaring, dabbing his streaming eyes with a vast silk handerchief.

The Colonel was astonished. 'What's the matter with the fellow? Has he gone mad or something?' And the paragon was forth- with transferred from acceptability to the remotest marches of strangeness.

Some 'of the other young officers caused the Colonel almost unbearable pain from the start. Evelyn Waugh's Lieutenant Hooper was typical of them all, clerkish NCOs commissioned from unfashionable, banausic formations like the pay and ord- nance corps, NQOCD, as debs' mothers were then supposed to put it — not quite our class, dear. He overheard with grief their flat, precise suburban speech, viewed even their strong points without proper en- thusiasm. They were mostly very good, for instance, at checking and re-checking their platoons' G 1098 — the complete inven- tory of equipment. An attribute not to be sneezed at, for what is the use of leading your men in a dashing upper-class way, of scorning convention and having nicknames like 'Boy' and 'Lucky', if face to face with the enemy you find — oh hell! — you've left half your weaponry behind. I lost my own pistol rather early on — not that I could have hit a gasometer with it, even from inside. My awkward antics with a pistol recalled Bob Hope rather than John Wayne. Far more effective in my hands was even the Sten, with its random bursts misfires and unpredictable explosions, ter- rifying alike to user, friend and foe.

It was the Colonel's settled conviction that these commissioned pen-pushers and orderlies, `oiks' and 'grocers' (a snob word in use long before Private Eye attached it to Mr Heath), would all be happier and better suited in the searchlights. A kindly man, he devoted unwonted energies and even cunning to effecting these beneficent transfers. He would call the oiks' guards out at short intervals and unexpected times. One of them, with a bad attack of the trots, was caught giggling literally with his trousers down. I often wondered what the searchlights made of the gifts showered on them by the Colonel's social selection system. Perhaps they valued what he dis- carded. At least their lights would be present, polished and in working order. Nor could the German bomber caught in a hostile beam discern whether it was directed by someone with his trousers off or not.

Like other prejudices, the Colonel's snobbery may have had some occult rationality in it, ill though it chimed with a People's War in the Century of the Com- mon Man. It was often said that infantry soldiers didn't much like being corn-

manded by upstart members of their own class, still less by promoted clever dicks from what they regarded as inferior mobs, administrative or supportive rather than brutal and licentious in character. They apparently preferred their officers a bit grand, odd, boozy, dashing, eccentric or even mad, humorous by nature or intent, to be celebrated in boastful anecdote or affectionately irreverent nickname. And of course officers produced by the inscrutable workings of a seemingly irrational class structure had at least the merit of having no damned merit nonsense about them. Respect for them was not enforced by some unchallengeable logic, though, if won, it was an enduring asset.

Towards the end of the war, anyway, there simply weren't enough more or less upper class officers to go round. Some of the gentlemen called in to fill the gaps were very temporary indeed, far from parfait: the flashy heirs of rich pork butchers, 6 One of the characteristics the Colonel shared with other great commanders was the ability to drop off for forty winks in all

circumstances.

endowed with sports cars and black market petrol, public relations types and salesmen, even, to the Colonel's distress, actors. The obvious way out of these difficulties was to commission lots of those excellent infantry. NCOs. The trouble was that all the tackles' and 'Boys' were peculiarly de- pendent on good NCOs, who thus became precious, indispensable, to be hoarded like gold, and on no account to be recom- mended for a commission, which would normally mean their loss to some other regiment. The banausic corps, having an inexhaustible surplus of technically compe- tent bods, were far more generous with their recommendations. This was sad, as I'm sure the Colonel would have agreed.

One of the characteristics which the Colonel shared with other great comman- ders was the ability to drop off for forty winks in all circumstances. Papa Joffre must have had that gift and at Tannenberg the battlefield guides used to point out various spots to visitors: 'Here Hindenburg slept before the battle; and here he slept after the battle; and here he slept during the battle.'

Our division had had a long, hot day at a Suffolk field-firing range, culminating in a night attack and a long drive home in the dark. The Colonel composed himself for sleep in the back of his Humber, delegating the task of map-reading to the battalion intelligence officer: he was not a man to keep a dog and bark himself. The I0 sensibly attached himself to the last vehicle of the battalion in front. Under the tail board it bore, dimly lit, our divisional sign. The great convoy set off. Confidently following his leader, the tired 10, too, relaxed. Round a corner and, lo, horrors! The road ahead was empty, nothing in sight. Frantically he ordered the driver to step on the gas. His torch wandered wildly over the map: where on earth were we? `Left here, must be left again — no, right. Oh damn — make two lefts. Faster! We must catch them up.' Unheeded in the rush, unfamiliar soldiers leapt belatedly shouting from an open road block. The road widened dramatically, became con- crete — were we on some by-pass? A huge and dramatically swelling mass of darker darkness materialised straight ahead, blot- ting out the stars. With a fearful roar it suddenly rose up, soared, missing the Humber by feet. We were on an airfield, from which a bomber had just taken off.

During the ensuing chaos and confabula- tions, the Colonel stirred uneasily but did not finally surface. At length the convoy was re-formed, and set off headlong into the dawn. Along twisting lanes and through farmyards we thundered, scatter- ing chickens astonished and half-awake, reaching at last a road and then a better road, and at last -- joy! — the distant divisional tail sign of a vehicle speeding lickety-split far ahead, presumably the last of our preceding battalion. The I0 breathed an enormous sigh of relief: 'fol- low that tail light,' he cried. No easy task, for it was receding at a fantastic pace, quite unlike the normal, stately Brucknerian adagio, langsam and feierlich, of a military convoy.

It grew lighter. The Colonel awoke, stretched and peered out of the window. Odd, he mused at last, how alike these Suffolk churches were. Doubtless a local style of mediaeval architecture, the IO, a cultivated man, suggested. Strange all the same, the Colonel rumbled; as yet another church sped past, exactly like its predeces- sors.

Whatever misgivings may have assailed the IQ it was the Colonel's keen insight which first realised that we were passing not similar churches but the same church over and over again, the same pub, too, with the same sign. The battalion transport had got itself into a huge circle. The tail the I0 was chasing was his own. Moreover, the convoy was not quite long enough to fill the whole circle with ease. Hence the ever increasing speed as each vehicle strove in vain to keep up with the one in front. 'Very odd indeed' was the Colonel's first reaction. Reflection and wrath sup- plied him later with language stronger than he normally used.

The demands of garrison duty at Dover later forced us to do night battle exercises in the country during daylight. To one of these the Colonel added a touch of realism by nodding off on his camp bed. Now battalion 10 myself, I stayed awake. Over the sunny hill two figures approached slowly in an odd manner. One would walk forward a few paces and then stop. The other, who appeared to be reading a compass and giving instructions, would then join him. The process was again and again repeated. I woke the Colonel, who was so astonished by these mysterious movements that he could hardly pull his trousers and boots on. His eyes stood out like gobstoppers. `God bless my soul: who are these strange people? Are they mad?'

I had recognised our new hyper-keen Brigadier, who wore enormous spectacles with heavy black rims like a Hollywood film director. I stepped forward to salute and delay him while the Colonel completed• his toilette. 'Good morning, Sir,' I cried. `Good morning?' the Brigadier testily riposted. 'It's good evening if anything. And who am I? It's pitch dark. You can't see me.' The Colonel joined us, his mouth hanging open in anxious disbelief. `Where's your commanding officer?' rap- ped the Brigadier, looking straight through the Colonel as if he wasn't there. `I'm here,' he faltered. 'I can't see you,' barked the Brigadier:`Identify yourself.' The Colonel later charitably acquitted the Brigadier of mental derangement. 'It must be trouble with his eyesight, poor fellow. Desert blindness perhaps. Those specs, don't you know. Very odd all the same. You really can't command a brigade if you can't see an inch beyond your nose. They ought to invalid him out.'

Our paths later diverged, mine to the Lincolns in Normandy, his to command a battalion there. I bumped into one of his chaps out of the line, and asked him how the old boy was getting on. 'He had a bit of bad luck the other day. Very nasty.' I froze, fearing catastrophe. `He'd managed to organise some breakfast for himself, you know, bacon, eggs, the lot — and he was sitting outside his command post, just about to tuck in, when a bloody carrier turned sharply in the dirt just in front of him. A huge cloud flew and fell splat all over his fry-up.' He must have been livid.' `Obviously, but all he said was "very strange", you know, in a mournful sort of voice, as if it were an act of God.' In every life, they say, some rain must fall. Blessed the life in which a ruined breakfast is memorably strange. Peace be with him.

Previous page

Previous page