IIISTORY OF WOOD-ENGRAVING. •

THE practice of illustrating books with wood-cuts is becoming so universal, that tun account of the history and process of this popular style of embellishment was a desideratum in literature ; which has been satisfactorily supplied by the treatise put tbrth by Mr. JOHN JACKSON. A costly volume, however, as this necessarily is does not conic within tine means of the mass of readers ; while minute details essential to an elaborate treatise on the art, and ti.. a work of research, are somewhat beyond their range of study : we therefore, now that tine recess of Parliament affords us an extent of column-room which we could not have commanded when the book first appeared, devote snore than usual space to a technical subjew with a view to supply as much information on the progress a. practice of engraving on wood, as may suffice to give our readers clear insight into the method by which the profusion of cuts are scattered through the publications of the day. The Penny Magazine, and other publications of' the Useful Know- ledge Society, or Mr. KNIGHT, were the first systematic attempts to apply the principle of teaching by pictures ; and Mr. LOUDON; in

his Cyclopmdias and Periodicals, has extensively employed them with excellent effect : scientific works as well as books of enter- tainment are beginning to adopt the pictorial plan of explanation.

Tine benefit arising from this union of delineations and description in the communication of ideas, is still not sufficiently felt : prints

are viewed in the light of extrinsic aids and accessories rather than as essential and intrinsically useful. Drawing is tine demon- strator of visible truths ; and though the pen may be tine prime mover of the reader's fancy, the pencil points the way to the percep-

tion of realities. Many matters of fact can only be stated clearly bsy lines : the plan of a building, a view of a place, a plant or an ani- mal, the structure of a machine, the form of a statue, can only

be distinctly represented by an image. In these days of cheap publications and steam-printing, the art that inlays the page with graphic exemplifications of tine author's meaning, without impeding tine rapidity of the printing process, and at a much less expense than plates of any kind, is of immense utility and importance. The reason why wood-engraving is not even snore employed, is undoubtedly the fact, that the art itself is not thoroughly under-

stood either by painters or the public : indeed, writers on its history have proved their ignorance of the process. People see and 11ar of wood-engraving, and think wood a very cheap substitute for copper ; they admire the ingenuity of the engraver on wood in coming so near to copperplate, and are very pleased to have a book adorned with wood-cuts at so small an additional cost : but they do not concern themselves further; they would be surprised to hear that the processes of engraving on wood and on copper are totally different, and that many " wood-cuts" are printed from metal. Before entering on the history of wood-engraving, therefore, it may be as well briefly to describe the nature of the process. It is the very reverse of engraving on copper; for though tine plate and tine block are each incised, it is the raised lines of the wood that yield the impression, while in tine copperplate it is the sunken lines. In printing from the block, consequently, tine ink is applied to tine surface, and the paper pressed on it by direct and instantaneous pres- sure, as in printing from types ; whereas in printing from copper- plate the ink is rubbed into the sunken lines, and the surface of the plate is cleansed, so that the ink being below the surface, the paper is pressed into the inked incision, by the progressive action of two small revolving cylinders between which the plate is gradu- ally squeezed. Types and wood-cuts are often printed by a machine' the pressure of' which is given by a revolving cylinder; but its diameter is so large that its action on each cut is as momentary as the vertical pressure of' an ordinary printing-press. Thus it is evident, that wood-cuts may be printed with type, but that copperplates cannot : and this constitutes tine advantage of wood-engravings over copperplates for tine illustration of books. Wood-engraving includes two distinct operations,—the one per- formed by the draughtsman, who draws the design on the block with a pen or pencil; tine other by the cutter, wino cuts away the blank lines and spaces leaving the drawing engraved in relieE The extreme delicacy, dexterity, and patient skill required to cut out cleauly, pieces of wood from between lines less than a hair- breadth distant from each other, so as to preserve the lines in re- lief perfect and unbroken, will be apparent on looking at any wood- cut of ordinary finish : and when it is borne in mind that the various tints are produced by the thickness or thinness of the lines, their nearness or openness, and the height of tine relief in different parts, tine niceness of the operation necessary to produce a satis- factory result is really surprising. Wood-engraving is a more ancient art than printing ; indeed it was the parent of this great civilizing power : from playing-cards sprung that mighty engine the press. Stamping from raised lines, figures, and letters, was practised from the earliest times ; as may be seen from cuneiform characters impressed on the Babylonian bricks, and a wooden brick-stamp found in a tomb at Thebes. The ancients branded their cattle, slaves, and criminals; and sovereigns and official persons used engraved stamps or stencil- plates to affix their signatures or monograms to documents. Jus- TIN, Pope ADRIAN, CHARLEMAGNE, and the Gothic sovereigns idea of' the action. England bad then no school of art, and the of Spain, adopted such contrivances ; and they were in ordinary designs produced were commensurately coarse. Of the use - lie rem use among the German and Italian notaries in the thirteenth wood-cuts at this period little seems to be known,—unless a cu. and fourteenth centuries. It is probable also that English mer- rious alphabet of figures in the Print-room of the British Muse chants of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries stamped their formerly' belonging to Sir GEORGE BEAUMONT, be ascribed Iiiti' commodities with the monograms or marks fbund on tombstones, country : they are among the finest specimens of the fifteenth &c. QUINTILLIAN, speaking of' teaching writing, says—" When century.

the boy shall have entered upon joining-hand, it will be useful fbr It would be tedious and profitless to follow the art. throughout bim to have a copy-head of wood, in which the letters are well cut, the various stages of its progress. Suffice it to say, that reached 1 that through its furrows, as it were, he may trace the characters perfection in the time . Of ALBERT DURER, and that the c• Tri. with his style :" and a "stencil-plate" of copper has been found umphs of Maximilian" are more {humus as the triumphs of wood. amongst old Roman coins. Yet for all these near approaches to engraving. Of this superb work HAss BURGMAIR was the prig, the principle of printing, it was reserved for wood-engraving to cipal designer: ALBERT DURER designed only a few cuts; bh

develop it, and that too as an accessory to the graphic art. great works, the triumphal car and - arch of Maximilian, being

Both wood-engraving and printing originated in Germany. The separate from the processional series. Ilomnases " Dance Of first wood-engravers were the German card-makers ; who, towards Death" and Bible cuts are among the best of the numerous illus. the end of the fourteenth century, cut the outlines of the figures in tratcd books that appeared in the early part of the sixteenth cen. wood, and, covering the surface of the block with some tenacious ink, tory, when the art had attained its perfection ; after which time, it took off the impression by friction ; the colouring was then added gradually declined and languished generally over Europe, till the by stencilling. The monks soon availed themselves of the orna- end of the eighteenth century. In 1754, J. B. JACKSON, a:Ens.or meats of " the Devil's books" to propagate their religion, and em- Hsi) wood-engraver, published a treatise on " Engraving and ployed the "form-schneiders," or figure-cutters, and " brief-milers," Printing in Chiaroscuro," that is, with colours from two or paper-stainers, to execute in this way the figures of saints, which three blocks, as practised by thaw di Carpa, who introduced this they distributed at the convents. The " St. Christopher," the style ; and in 1766, appeared PAPILLON'S History of Wood-Eis earliest wood-cut known, dated 1423, is executed in this manner. graving, the author being a well-known French engraver. This It represents the saint with the infitut Jesus on his shoulders, cross- proves that the art, though neglected, was not ibrgutten or lost jug a stream with a palm-tree for his staff; on one side is a mill, But the credit of its successful revival, at the end of the eighteenth and the miller carrying a sack of flour up a perpendicular path to century, is unquestionably due to our coun; union THOMAS Hewn, his house ; and on the opposite bank stands a hermit at the door who gave to wood-engraving a new character, and gained 14 it the of a watch-box with a bell at the top, holding a lantern the size high place in popular estimation which it now holds. The charm of of a parrot's cage to light the saint over. The action and drapery BEwlea's cuts is owing more to his mind than his hand, delicate of St. Christopher are worthy of ALBERT DURER : the folds of the and finished as was his execution : he was a great observer of nature, flying garment are well indicated by lines of various thickness and and always directed his skill to the imitation of natural appear. some touches of shading ; and the characters of foliage, not only of [IBMS in the objects he represented ' • in doing which, he mon. the cocoa-palm but of the trees on the bank, are discriminated : sciously acquired excellence of a kind hitherto unknown and the waves, to be sure, look like ribands, and the fish swim atop unsought as well as unattained : the picturesque feeling, and of the water, while the landscape shows a glorious disregard of shrewd moralizing humour, evinced in his cuts, made the public perspective, and the saint might stride, like the colossus he looks, like the sub'ects as much as they admired the art, whose beauties across the stream with one foot on each bank : yet still there are but for thi.:; they would have been slow to discern and appreciate, purpose, character, and meaning; and the art produced nothing The fatuous liaANsTus, who was, like 11Ewlex, self-taught, under. better afterwards till ALBERT DURER'S time. The size of this cu- valued liEvesces skill, and tried to excel him—but in vain: he rious cut is upright folio of eleven inches and a quarter high may have been more skilful in the mechanical part, but the mind and eight wide ; and underneath is the legend of the, saint, in two and fancy were wanting that render the cuts of Ilawietc works of lines, and the date. Other cuts of a similar kind are extant : this, genius in their way. WthmAst lif.tavvr, the favourite pupil of and one of the Annunciation, are pasted inside the covers of an BEWICK, is the most celebrated living designer of cuts : he came old manuscript entitled " Laus Virginis," finished in 1417, brought up to London, and studied under ILtynox,—whose knowledge of from the convent of Buxheim in Suable, and now in the collection the figure (as well as turgid style) is traceable in "Lima's de. of Earl SPiNCEIL In the Annunciation, the lines are more deli- signs : but for liAavEv, the progress of wood-engraving would cate, and the perspective is better ; but the spirit and character have presented a blank as regards poetic designs of figures, are inferior. Mr. 'HARVEY drew and cut one of the largest and most elaborate The " Block-books" next succeeded; consisting of forty or fifty wood-engravings extant, a copy of laynoN's " Dentatus :" it is pages, having two or more smaller cuts, composed of several figures, composed (.)f several blocks fitstened together. The success, how. and printed on one side only; the designs being explained by in- ever, is not answerable to the labour; and this extraordinary tsar scriptions, and the whole forming a consecutive history. Specimens de prce proves that the art has limitations that it is only wasting of these, such as the " Apocalypse of St. J01155," and the " Iliblia pains to attempt to pass. Happily, in art as in nature, there are rauperum"—to which our author adds the word " Predicatorunt," prescribed boundaries to man's ingenuity ; so that each new disco- " the Poor Preacher's Bible"—are in the King's Library of the very rather fills a vacuum, not tilt then perceived, than ::upersedes British Museum. " Donatuses" fbr boys are also among the block- what had gone before. The vocation of wood-engraving is to ilia. books. minute the text of printed boAs : the pre,s is its :,Itoet-anchor; A book called " Speculum Huntanre Salvationis" was the first in its connexion with typography conslsts its utility and beauty. in which moveable letters were used, but only partially. The JOHN THOMPSON, a pupil of 11u.s.ssToN, and CHARLTON NIAET, invention of types has been erroneously ascribed to I.AwttENCli pupil of BEwies, are the two first wood-engravers of the day: not COSTER : the honour of the invention of printing, history has shown ought we to pass unnoticed Le KE CLENNELL, also a pupil of to belong to JOHN GUTEMBERG, of Mentz ; who made types cut Bawler:, who engraved STommto's designs tbr ?dr. lloamtes out of metal in 1436. JOHN FAUST, whose name is popularly. Poems ; or JOHN BEW ICE., the brOtlhlr ilhd pupil of Timm IS. FM.. known as the discoverer of printing, only became the partner most among the engravers of the present time, are S mu ii and of GUTEMI3ERG in 1440 ; and live years after, he sued the inventor \'i \V I I.LIAMS, OR It I N SM ITII, LA N h I: LLS tile BB .1 NSTONS, for the money advanced, and dissolved the partnership. Having got and Worms. Some of these artists occasionally design, but they poor CUTE:MIMEO'S types and presses in satistitction, he then are for the most part engravers only. associated himself with Prima SCHEFFER, his son-in-law; who The great want is of designers ; and it is a reproach to the was the inventor of' the matrix for casting type. They together English school, that among the thousands of daubers laving claim brought out the Psalter printed at Mentz, in 1457 ; of' which to the title of artists, there should be found so few capable ofdntw- it is said, " The large initial letters engraved on wood and printed ing on wood: these persons affect to despise an art that employed in red and blue are the most beautiffil specimens of this kind of the genius or I tomnits and AmtEwr Dtmeat ; but the real secretof ornament which the united effbrts of the wood-engraver and the their assumed contempt is their utter inability to draw. Want of pressmen have produced." Of these rare cuts Mr. JACKSON gives knowledge of the vital and essential principles of their profession,

reduced file-similes. among the generality of painters, more than any other cause, int.

exactness accords well with the peculiarities of' this art ; the exercise tion we have abstracted.

coarse in comparison with the delicate inflections of their drawings works of Bewick again brought it into notice. * * *

for the pose of the figure, and the power of the lines to jeconvteoytavi admirable and interesting volume, which has supplied the intbrum-

of which is also suited to the patient, laborious Germans, their pre- " On taking it retrospective glance at the history of wood-engraving, it will cision, and love of minute elaboration. TITIAN and BUBENS both be perceived that the art has not been regularly progressive. At one period ire essayed designing on wood, but it did not suit the taste of colour- finti its productions distinguished for excellence of design and freedom of mop

tion and at another we

late : the Florentine painters too, for all their neatness and pre- find mere mechanical labour substituted for the talent cision in delineating form, it is natural to suppose, were not of die artist. As soon us this change commenced, wood. engravings a

it means

enamouredof an art whose success of multiplying works of art began to decline. It continued in a state of ne successful efforts appeared rude and -

glect for upwards of a century, and showed little symptomsof revival until. the

with the cost of printing steel or copper plates separately, the art will never

wont encouragement, nor again sink into neglect, so long as there are artists of talent to ffirnish designs, sad good engravers to execute them." To Mr. JOHN JACKSON the world is indebted for originating the most correct and complete history of this art that has appeared: be conceived the idea, collected a portion of the materials, en- graved all the cuts, and produced the work at his own expense. Nikita!, however, is greatly 7ing to the industry and acuteness of his literary coadjutm, Mm. \V. A. Cittrro ; whose able assistance JACKSON acknowledges. Mr. CoArro is the author of the Dlr. historical" portion, which occupies seven out of the eight chap- "

ters of which the volume consists; the materials for the "practical" pea being supplied by -Arr. JACKSON. Mr. CHATTO is a keen con- troversialist, and has exposed the blunders, delusions, and loose statements of previous writers on the subject, with caustic clever- ness: he writes, however, with the discrimination and gusto of a inan of taste and sense ; and we have not hesitated to take for granted the correctness of his statements, on the ground of the proofs and arguments he adduces. The versatility of skill shown bv Mt. JACKSON in his execution of the reduced fite-similes of old cuts of different masters and countries, proves his title to a high standing in the proti:ssion. It is, indeed, a thrtunate cir- cumstance that wood-engraving illustrates its own progress.

Of the details of the process we shall let Mr. JAcKsoN speak for himself, in the following extracts from the chapter on the practice of the art : the description of it given at the outset of this notice will suffice to make them intelligible to the readers without further explanation.

wool) USED FOR ENGRAVING.

no other idiot of %vocal hitherto tried is equal For the purposes of engraving,

to hos. bor tine and small cuts the simillest logs are to he preferred, as the smallest wood is almost invariably the hest. American and Turkey box is the largest ; hut all large lewd of this kiwi is generally of an inferior quality, aud most liable to split--; it is also frequently of a red colour, which is a certain characteristic of its softness, and coosequent unfitness for delicate engraving.

From my own experience, 'English box is superior to all others ;l or though math it is generally so clear nod tinn in the grain that it never crumbles under the graver ; it resists evenly to the edge of the tool, and gives not a par- ticle beyond what is net sally cut out. The large rist wood, on the contrary,

besides being soft, is liahle to crumble and to cot short ; that small particles will sometimes break away from the sides of Ihe line cut by the graver, and thus cause imperfections in the work. Box of large and comparatively quick growth, is also extremely liable to shrinv. unevenly between the rhigs, so that after the surface has bee11. planed perlietly level, and engraved, it is frequently difficult to print the cut m a proper manner, in consequence or the inequality- of the suffice.

As even the largest logs of box arc of comparatively small diameter, it is ex- tremely difficult to obtain a perfect block of a :tingle piece equal to the size of an octavo page. In order to obtain pieces as large as possible, some dealers are accustomed to saw the log in a slanting direction—in the manner of an oblique section of a cylinder—so that the suffice of a piece cut oh' shall resemble an oval mtlwr than a circle. Bloeks sawn in this manner ought never to lw used ; for, in consequence of the obliquity of the grain, there is no preventiog small particles tearing out when cutting a

Large red wood containing while spils or streaks is utterly malt for the pur- poses of the engraver ; for in cutting a line across, adjacent to tlICSe spots or streaks, sometimes the entire piece -thus marked will be removed, and the cut consequently spoiled. A clear yellow colour, and as equal as pos,ible over the whole surfitce, is generally the best criterion of box-wood. When a block is not of a clear yellow colour throughout, but only in the centre, gradually be- coming lighter towards the edges, it ought not to be used for delicate work ; the white, in addition to its not cutting so "sweetly," being of a softer nature, absorbs more ink than the yellow, and also retains it more tenaciously, so that impressions from a block of this kind sometimes display a perceptible hiequality of colour.

SKILL NECESSARY FOR in:suixixo.

An artist's knowledge of drawing is put to the test when he begins to make designs no wood, he cannot resort, as ni painting, to the link of colour to con- ceal the defeets of his outlines. To be efficient in the engraving, his principal figures must be distinctly made out; a drawing on the wood ;Aims of no sons- bass; black nod white are the only niemuims by which the subject can be repre- sented; and if' he be ignorant of the proper management of ehiaro-curo, and incorrect and feeble in his drawing, he will not he able to prothwe n really good design for the wood ClIgraVer. Many persons can intim a tolerably good picture whore utterly incapable of making a passable drawing on wood. Their draw- ing will ind stsnd the test of simple block and white ; they can indicate gene- ralities " indifferently well" liy means of positive coheirs, lint they cannot de- lineate individual forms correclly with ilk. hhick-hael pencil. Tm I.,. from this cause that we have so very few persgits who professedly make designs time wood- engravers ; and hence the sameness of character that is to be faintl in so many hoiden' wooml'emmts.

METHOD OF PRODUCING FAINT TINTS.

As what has been previously said about the practice of the art relates en- tirely to engraving where the lines areof time sante height, or in the same plane, and when the impression is supposed tm be obtainod by the pre-sure of it limit maim:, I shall now proceed to explain the pray: lee of lower it g, by which ope- ration the suffice of the block is either st•raped awsv from the centre towards the sides, Or, IIS may be required, hollowed out im I al licr 1mb Wt.,. The object of' thus lowering a block is, that the lines in such places mmmli Ii Ims exposed to pressure in printing, and thus nppear lighter than if they etc of the same

height as the others. This method, though it has liven rim ii as a modern invention, is of considerable antiquity, havisig been practised in 1:sts. instances of lowering are very frequent in cuts engraved by Bewick ; hut until mm mm mu the last five or six years the practice was not resorted to

Ly South-country engravers. It is absolutely necessary that wood-cuts intended to he printed by a steam-press should be looered 1mm surh parts as are to appear light ; for, as the pressure on the cut proceeds from the even sort:tee of a metal cylinder covered with a blonket, there is no means of lidpuuiga cut, as is generally done when printed hy a hand-press, by metals of overlays. Overlaying consists in pasting pieces of paper either on the front or at the back of the outer tympan, immediately oyes such parts of the block as require to be printed dark ; and the effect of this is to hos ease the action of ffic platten on those parts, and to diminish it on such as are not over- laid. When lowered blocks are printed at a conimon press, it is necessary ;hat a blanket should be used in the tympans, in order that the paper may be prbessed into the hollowed or lowered parts, and the lines thus brought up. 'te application of the steam-press to printing lowered wood-cuts may he con- idered as an epoch in the history of wood-engraving. Wood-cuts were first printed by a steam-press at Messrs. Clowes and Sons', about six vears ago : and since that time lowering has been more generally practised than at any former period.

A cut which is properly lowered may not only be printed by a steam-press without overlays, but will also afford a much greater number of good impres- sions than one of the same kind engraved on a plane surface ; for the more delicate parts, being louver than those adjacent to them, are thus saved from too much pressure, without the necessity of increasing it iu other places.

CARE REQUIRED IN pluNTING.

The want of something like a uniform method of printing wood-cuts, and the high price charged by printers for what is called fine work, have operated most injuriously to the progress and extension of wood-engraving. The practice, however, of printing wood-cuts by a steam-press, or a press of any kind with a cylindrical roller instead of a platten, seems likely to introduce a general clump in the practice of the art. By the adoption of this cheap and expedi- tious method of printing, books containing the very best wood-engravings can be afforded at a much cheaper rate than formerly. As cuts printed in this manner can rereive no adventitious aid from overlays, the wood-engraver is re- quired to finish his work perfectly before it goes out of his hands, and not to trust to the taste of a pressman for its being properly printed. The great de. sideratunn in wood-engraving is to produce cuts which can be efficiently printed at the least pos,ffile expense; and as a means towards this end, it is necessary that cuts should require the least possible aid front the printer, and be executed in such manner that, without gross negligence, they will be certain to print well. The greatest advantage that wood-enoraving possesses over c»graving on copper or steel, is the cheap rate at which its productions can be printed at one impression, in the sante sheet with letterpress. To increase, therefore, by an incomplete method of engraving, the cost of printing wood-cuts, is to aban-

don the great mum it of the art.

The mode of printing by the common press without a blanket, and of helping a cut engraved on a plane surface by means of overlays, is not only much more expensive than printing from a lowered bloek by the steam-press, or a common press with a blanket arid without overlaying, but is also mouth more injurious to engraving. As the block is originally of the same height as the typo, it is evident that the overlays must very much increase the pressure of the platten on such parts as they are immediate7ly above. Such increase of pressure is not only injurious to the engraving, occasionally breaking down the lines, but it also frequently squeezes the ink from the surface into the interstices, and causes the impres- sion in such parts to appear blotted. While a block with a flat surface, printed in this manner, will scarcely afford five thousand good impressions without re- touching, twenty thousand can be obtained from a lowered block printed by a steam-press, or by a common press with a blanket and without overlays : the darkest parts in a lowered block being no higher than the type, and not being overlaid, are subject to no unequal pressure to break down the lines, while the lighter parts being lowered are thus sufficiently protected. The intervention of the blanket in the latter case not only briugs up the lighter parts, but is also less injurious to the engravings than the direct action of the wood or metal platten, with only the thin cloth and the parchment of the tympans inter- vening between it and the surface of the block.

rrrEcrs or BA)) PAPER ON THE CUTS.

When wood-cuts are printed with overlays, and the paper is knotty, the en- graving is certain to be Injured by the knots being indented in the wood in those parts where the pressure is greatest. When copies of a work containing wood-cuts are printed on India paper, the engraving is almost invariably in- jured, in consequence of the bunt knots and pieces of hark with which such paper abounds, causing indentions in the wood. The consequence of printing off a certain number of ct,pies of a work on such paper may be seen in the cut of the Vain Glowworm, Ill the second edition of the first series of Northcote's

Fables: it is covered with white spots, the result of indentions in the block caused by the knots and inequalities in had India paper. Overlays frequently shift if not well attended to, and cause pressure where it was never intended.

In order that wood-engravings should appear to the greatest advantage, it is necessary that they should he printed on Itrolwr paper. A person not practi- cally acquainted with the subject may easily he deceived in selecting paper for it work containing wood-engravings. There is a kind of paper, manuffictured of coarse material, which, in consequence of its lieing pressed, has ri smooth appearimee, and to the vievy seeniS tO he highly suitable for the purpose. As SU011, however, as such hiap.r is wetted previous to printing, its smoothness dis- appears, 1 11.1 its hill W14.0.'6111, become apparent hy the irregular swelling of the material of which it is compt,ed. Paper intended for print mug the best kind of wood-cuts ought to he even in test use, and this ought to be the result of good material well ma it utbet med. Paper of this kind w ill not appear uneven when wetted, like that which has merely a yo,(/ firce put upon it by means am. treme presure. The best mode 4.,1* testing the (humility of paper is to wet a sheet ; how everieven and smooth it may almear when dry, its imperlietions will be evident when wet, it'll be manittlictured of coarse material, and merely pressed smooth.

Paper of unequal Illickne, how ever pond the material may lie, is quite unlit lin. the purpose a printing the best lsind of wood-engraving, ; for if a

Shed be thmirkr II out coil till!) tilt' there Will 1.1• ditlin- ence in lime stremo h of the inipre,..im.s of the cuts accordingly as tImer may be printed on the thick or the thin parts, Ii mm- on the latter being light, while those OIL the former are comparat 0 els' hes\ y jr dark. AVI:VII it is known that an overlay of mime thinnest ti,stie paper will make a perceptible difference in an hopressioa, the necessity It. [lasing paper of even texture Mr the purpose of plinth), vs...oil-cm, well, is olw ion,. As there is less chance of inequality of texture in compratively I hin paper t hall mm t It:ek, the limner kind is generally to he preferred, supposing it to he equally manulitet tired.

The advantage that pictures have over verbal descriptions, will speak to the eye in the illiislratire appcndix subjobwil to this ac- count of wood-engraving : the actual cuts (which by the liberal courtesy of the proprietor we are enabled to supply fr(an time book itself') demonstrate, better than the nicest discrimination could do, the progress of the art, and the characteristics of different artists. The peculiar style, and relative merits of the wood-cuts of Ger- many, France, Italy, and England in the fifteenth century, may be traced in the first four; the next fbur exhibit the perfection of the art in Germany ; and the last four its revival and present state in England. The last two examples of the skill of our countrymen, however, are selected with it vicw to exemplify the opposite ex- tremes of a picture of many details, and one of broad effect. Though BEwica, were he living now, might not be surpassed in the spirit of his designs, there are many engravers of the present day who could vie with him in finish and elaboration. As specimens of Mr. JacxsoN's engraving, they must be regarded with abundant allowance for the defects of newspaper-printing by steam and cylinders : the typography of the 'Spectator, though none of the worst, may not compare with that of Mr. JACKSON'S book.

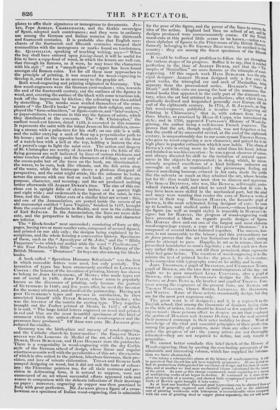

No. 1. St. Christopher. 1423.

A reduced copy of one of the. earliest known wood-cuts, engraved by one of the old Gentian card-makers, and in the original coloured by stencilling. The action• of the fignres, and the folds of the drapery, show the comparative perfection attained in this.first effort of the art.

. No. 2. Letter k of .the Alph2bet. Circa 1450.

• A facsimile, the sire of the Original cuts of the alphabet : they are printed

In a sepia-coloured ink of distemper. From the style of design, and the air of the kneeling suitor; who with one hand offers a ring to his mistress, while theothet holds a scroll inscribed "mon ame," it has been conjectured that they are by a French designer; though the word "London" is seen on a sword- blade in one of the other letters. No. 3. Cross-bowman, 1483.

Fae-simile of a Cain the edition Of VALTITRIUS " De Re IsdilitariNtha lished at Verona,'1483; the. second book printed in Italy with wood•cuti:—i is given in order to show the contrast between the German, French, ant Entg: lish styles of design, and how much grace of form can be eenveyederesol, coarse outline.

No. 4. /Cnight. Circa 1476.

A reduced copy of the Khight from the second edition of CAXTON'S "Gov nnd Playe of the Chessc," a small folio published about 117(; the first primal book in the English language that contains wood-cuts. The uncouth deiip end barbarous execution contrast strongly with the tutistical (politics of the three preceding specimens.

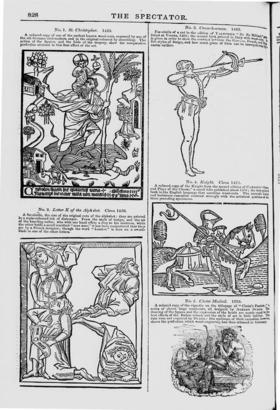

No. 5. Christ Mocked. 1510.

A reduced copy of the vignette on the titlepage of "Christ's Passioti;" a series of eleven large wood-cuts, all designed by ALBERT DUREE. The drawing of the figures and the expression of the heads are nearly equal to the best efforts of the Italian school, and the style of art is little inferior. The cuts were not engraved by Duitim : this specimen of their execution, however, shows the perfection which wood-engraving had then attained in Genus* No. 6. Portrait of Albert Durer. 1527.

of Me porttait of ALBERT Donsa,.eleven inches and a half high by ten heledesusieeddec,°YraYwn by himself on.wood; and conjectured te be the last drawing he e. It is given chiefly for the interest of the resemblance. lint also to show how cony the engraving appumehes the character of etching on copper.

No. 7. Standard-bearer. 1519.

Reduced copy of one of the standard.bearcrs in the " Triumphs of Maximilian/ designed by HAN8 BURGMAIII : the initials of his name being bible on the trappings onlic base. It is only an average specimen or that extraordinary work, loaf to re. mumble fi,r lightness and freedom of draahig, and the ■alue of every line in caleg the forms, No. 8. Death and the Child. 1538.

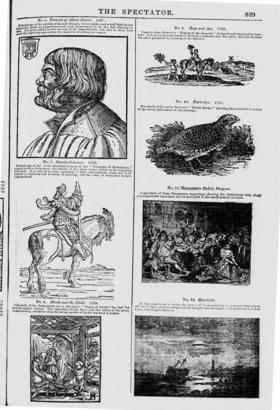

A toe-simile of the thirty-ninth cut in Harmsn's " Dance of Death," the last but twain the original edition. The expression in the faces and the action of the group nos/Unordinary, and show what the art is capable of in the hands of a master. No. 9. Boys and Ass. 1790.

Vignette from Brwicit's "history of Quadrupeds," &signed and engraved by him - self. It is given as a specimen of BEWICK'S humour, and free style; arid also to show the effect produced by lowering in the distance.

No. 10. Partridge. 1797.

Fac-simileof the cut in Ilsnermes " British Birds ; " showing his successful imitation of the colour and Matisse of the plumage.

Ne.11:HoaAirra's Bahe's Progress.

A specimen of Jotter Trrourson's engraving ; showing the distinctness with w1411 physioptomical expression can be conveyed in the smallest scale on wood.

No. 12. Mow:light.

Iii Ibis ennst•sei ne is shown the pw r sf wombengraring Iire;:rawatt atmospheric effects of light, disrrinliartling lattrtui sunlight and sauliblight ; id producing a uotiow t 0:1e, with bright reflection.

MORTON OF MORTON'S HOPE.

THESE volumes display considerable talent, though they form a very indifferent fiction. The author is a man of various reading, and some experience in the manners of different nations ; or of great dex- terity in turning a little to account. He also has a knack at seizing the salient points in character, of sketching isolated scenes, and in- venting or reporting social discourse. His style is short and rapid, with a point which seems to have been borrowed from BULWER : like that writer he has a turn for the ridiculous and the satirical, which he applies on all opportunities without regard to their fit- ness ; and he is a just but not a very profound thinker, though he apes profundity. His sketches of persons, incidents, scenes, and dia- logues which have little or no connexion with the story, are smart and animated, although often affected. But he wants the genius to create a fiction, and is devoid of art and experience to contrive one. As soon as his hero, or any other person, is plunged into a story intended to be interesting, propriety and probability are set at defiance. Every incident, if not dull under the pretence of being natural, is startling, exaggerated, or horrible, sometimes monstrous in itself, and almost always so in connexion. For ex- ample, in the course of a few pages we have a German wife going mad and throwing herself out of window, the husband murdering his brother-in-law in the street, stabbing his father-in-law before the tribunal, and poisoning himself in open court—like HANNIBAL, with a ring; and all for no other reason than the vitiated taste of the author. After figuring as a buccaneer, a whaler, and a frontier warrior, a poor devil is thrown amongst the Red Indians to see or suffer all they inflict upon their enemies in captivity and war, ac- cording to "authority ;" though Indian usage is set at defiance in the treatment of the prisoner. And to show his laxity in the least things, a lady, married and sent to England, is found a few weeks after, not even a novice, but a nun ; whilst an American gentleman is made to contemplate a cotton speculation before ARKWRIGHT had brought his inventiers to bear.

'rho author states on several occasions that he has a moral pur- pose in view ; but as we do not very clearly catch it, and are tolerably certain he has not worked it out, we may pass it over. The mode of fiction he has chosen is the autobiographical : Mr. Morton, of' Morton's Hope, (a " pine plank and shingle" villa, near Boston, U.S.,) narrates his own adventures. The framework adopted is the fragmentary-dramatic : there are five " books," ana-

logous to acts, the majority with large gaps of time intervening, and by no means connected with each other by the militia juncture. The first opens in America, about 1760; and narrates, with a forced

and flat attempt at humour, the early years of the 'hero; as well as the first riotings which heralded the War of Independence. This part closes with a turgid and melodramatic termination to Mr. Morton's first love adventure, which drives him to Europe ; and in book the second we find him in Germany, a witness or partaker of all the excesses and absurdities of the German students, ending with a band of them turning robbers in the Harz Mountains. The third and fourth acts show Mr. Morton at Prague, where he is studying natural philosophy ; having previously investigated history, "traced the Muses upwards to their springs," and eschewed meta- physics after detecting their fallacy, besides making the tour of Europe, and swimming "in a flat-bottomed scow on the Nile." The result of a heartless and brutal intrigue in which he engages, coupled with a letter from America, send him across the Atlantic ; and the fifth act finds Mr. Uncas Morton engaged in the struggle for American independence ; where, of course, he does good ser- vice, discovers his father, (whose autobiography is also printed,) and closes his tale when matter, inclination, or three volumes are exhausted.

The best descriptions of manners and character, with the most probable incidents, dramatically told, are the accounts of the doings of the German students at Leipzic and Gottingen, and the Red Indian campaign. The former seems to be painted by a man who has witnessed the pranks of a German University ; and the latter, though not professing to narrate matters which any one living could have observed, has minute touches which indicate that the author has seen a living Indian. The reflections in passing, and the disquisitions and digressions on subjects which the narrative turns up in its progress, are pretty freely scattered ; and from these our extracts will chiefly be taken.

THE SPIRITS OF THE AGE.

Ile laid his finger on my shoulder, and assumed a grave demeanour as he con- tinued—" Morton, remember this. If you have any ambition, any desire for distinction, its field and its satistiiction must be sought for in your own neigh- bourhood. The material out of which one must carve the statue of his reputa- tion, must be sought for in the earth beneath his feet—the only quarry of en- during marble you will find in the soil of your country. Study your age, study your country, and investigate and work upon the materials you find. It is only the imbecile who complain of their unfitness for their age or country ; the master-spirits seize the times, and mould them to their will."

THINKING AND ACTING.

" Well, well," said I, beginning to be bored with this homily, " time enough ; time enough. We are both young, there is no hurry."

"There again," said he quietly, "there is another vulgar error. I tell you, Morton, that the only difference between intellects, between characters, between men, is simply the difference between thinking and acting. Any one can think, any one knows what one ought to do to become great ; but few act, few do. A catalogue of actions is the only history and the only biogra- phy worth heeding. If you tell me that a man is clever—is a genius—I shall ask you simply what has he done? To do is the only proof that I will accept of genius. No hurry, no hurry, you say ; very well. But recollect, that while you are shivering and hesitating on the brink, another will have breasted the waves, and crossed the torrent ; while you are bundling and sharpening

your arrows, another will have struck the deer." '

This night I determined to act ; I determined to be joyous sina happy, it is only the effort in such cases that is painful. Chain down your heart 'fb a moment, and it will lie still in fetters. Swallow the first throb of your aa and you may dance on the grave of your mother. Bat mistake noir" feigned and frantic merriment for joy. The serpent shrinks and collect: away, but only to meditate a new and more venomous attack. Think net that you have wrestled with your anguish till you have destroyed it. k cowardly foe, and slinks away when it is attacked ; but wait only till row quiet or exhausted, or asleep, and see if it dues not return with a h;gioni fiends at its back.

aTTINGEN

Is rather a well-built and handsome-looking town, with a decided kaki the middle ages about it. Although the college is new, the town is ancient, and like the rest of the German university towns, has nothing external, with the exception of a plain-looking building in brick for the library and 04 or two others for natural collections, to remind you that you are at the scat of an institution for education. The professors lecture end] on hie account at his own house, of which the basement floor is generollv made use of as an auditorium. The town is walled in, like most of the Coniinental cities of that date, although the ramparts, planted with linden-trees, havesinee been converted into a pleasant promenade, which reaches quite round the total, and is furnished with a gate and guard at the end of each principal arenas It is this careful fortification, combined with the nine-story houses and the narrow streets, which impart the compact, secure look, peculiar to all the Cermet; towns. The effect is forcibly to remind you of the days when the inhabitant; were huddled snugly together, like sheep in a sheepcote, and lucked up safe from the wolfish attacks of the gentlemen highwaymen, the ruins of wheK castles frown down from the neighbouring hills. The houses are generally tall and gaunt, consisting of a skeleton of frame. work filled in with brick, with the original rafters, embrowited I•y time, pT0. jecting like ribs through the yellowish stuceo'which covers the surface. Thy are full of little \ vindows, which are filled with little panes; and as they are built, to save room, one upon another, and consequently rise generally to rigid or nine stories, the inhabitants invariably live as it were IR layers. Hence it is not uncommon to find a professor occupying the two lower stories or strata, a tailor above the professor, a student upon the tailor, a beer-seller conveniently upon the student, a washerwoman upon the beer-men:luta, amid perhapsa poet upon the top—a pyramid with poet tar its apex and a professor futile base !

As we passed the oh! Gothic church of St. Nicholas, I observed through the open windows of the next house a party of students smoking and playing billiards, and I recognized some of the thces of my Leipzig acquaintance, la the street were plenty of others of all varivtie::; sorne Nvitii plain naps and clothes and a meek demeanour, sneaked quietly through the streets, with pt. folios under their arms. I observed the care with which they turned out to the left and avoided collision with every one they met, These were " camels," or studious students returning from lecture ; others swaggered along the side. walk, turning out for no one, with clubs in their hands and ball-dogs at their heels ; these were dressed in marvellously tine caps and Polonaise coats co- vered with cords and tassels, and invariably had. pipes in their mouths, nod were fitted out with the proper allowance of spurs and moustaeldos. These were " Renommists," wit° were always ready for a row. At almost every corner of the street was to he seen a solitary individnalof this latter class, in a ferocious fencing attitude, brandishing his club in the air, and cuttilm quart and tierce in the most alarming manner, till you were tee minded of 'the truculent Gregory's advice to his companion, " Remember thy swashing blow." All ohm; • the street I saw, on looking up, the head and shoulders of students projecting from every window. They were arrayed in tawdry smoking-cape and heterogeneous-looking dressing gowns, with the long pipes aud dash tassels depending from their mouths. At his master's side, and looking out of the same window, I observed in many instances a grave and philosophical-looking poodle, with equally grim moustachios his head reposing contemplatively oa his fore-paws, and engaged apparently, like his master, in ogling the ponderous housemaids who were ''drawing water from the street-pumps.

GERMAN TITLES.

Nowhere, in fact, are such fine distinctions in the forms of address obscised as in Germany. The system is complicated, mid extends frmn the lowest to the highest grades of society. If you write, for example, to a shoemakeror a tailor, 3.ou address the " well-born " tailor Sehneidertf, or his " well-bora- ship" the shoemaker Remoter ; but if to gentleman, whose name has the ma• gical prefix Von, you style him the " highlv-well-born " Mr. Von liatyen• jammer. A count of the empire is " high-ho'rn ; " a prince is not born at all, but is addressed as His Serenity or (literally) Ilis Transparency, (Dods.

laucht) ; a minister of state, or an ambassaifor, is Excellency; hut the prorector of an University is his Magnificence.

THE RIGHTFUL PROFESSORS or ENNUI.

It seems to me that one great reason why the English, as a nation, are each victims of ennui, is because there is so large a class who have exactly no otket profession. Do not mistake me. I do not speak of men of large fortunes. liietpiie an opulent landholder, who is or affects to be an ennuy6. If he be really so, its goes a weakness of intellect, and there is nothing more to be said. But if he affects it, he excites my indignation, for I consider it an infringement on my own rights. The class to which I belong is a large one, and. I claim for it the ex- clusive monopoly of ennui. It is composed 'of men of good birth and small fortune ; younger sons of younger brothers, and in short of exactly that sort of people who have absolutely no niche in society, no place in the universal machine. It is exactly these sort of people who, if they here are absolutely destitute Of property, seem born for nothing but to be citrates in unknown Welsh parishes, or to be knocked on the head in obscure East Indian campaigns ; men too high- born to improve their fortunes in lucrative professions, too insignificant to be worth a great man's while to push them up the ladder of promotion. And then, if we have a little miserable competence, as is more particularly my awn .case, why so much the worse. It is then that we are obliged to adopt ennui 030 trade. We cannot hold soul and body together in England on our stipendond

so We go into exile immediately. We wander through the world ithot aiOi met

or object ; we lounge through life doing, nothing and expecting nothing;

when we Elie, we have not even the satisfaction of diminishing the population of our native country.

Previous page

Previous page