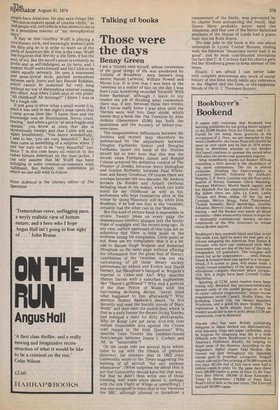

Fiction

Time capsules

Peter Ackroyd

Happy Endings David Cook (Secker and Warburg with Alison Press £2.25)

The Sightseer Geoffrey Wolff (Hamish Hamilton £2.75) It is not generally known that most contemporary novels are written over twenty years ago. Whenever "I" or "me" (and I shall be returning to this unhappy pair a little later) sip their first martini in a carefully detailed apartment, whenever a plot surrounds the narrative like a winding sheet and whenever 'characters' talk as if they were writing profiles of themselves, you may be sure that the book, even if it was composed just yesterday, belongs to an earlier and happier time when novels were about 'people' or 'society' or 'emotions or any of the other bleeding metaphors of the 'fifties. I am by now accustomed to this time-warp, and even try to reach down to the poor novelists by writing a lumpish and old-fashioned prose, and so I was agreeably surprised when Happy Endings turned out to be a very different kind of novel.

It is, on that technical surface which some critics call 'story' and others call persiflage, the childhood history of Morris West; young Morris has been caught inside or just between an even younger girl, and has been sent off to a 'home' to be denatured and assessed. It is at this extremity that the novel comes into its own as Cook yokes a straight and denotative realism to a world as small as it is dark. By the simple expedient of introducing into his narrative those varieties of prose which are all around us and which everyone except the modern novelist notices — the comic strip, Reader's Digest, and those demotic cliches which are the life blood of the language — Cook opens Happy Endings out into an unclassifiable but contemporary world. It gives his characters a cartoon garishness and a hard edge which the twentieth century has the right to expect, and this is the substance of the book, but! am afraid that there are times when Mr Cook loses his artistic nerve and returns to a conventional humanoid mess.

He introduces an art-teacher, Stephen, who is clearly to be taken as a simulacrum of Morris and between them Cook paints a picture of human inadequacy which is both sad and funny, in the usual vulgar way, and is probably meant to be universal. I prefer my comedy straight. As it is, Stephen strikes a note of muggy misery which Cook and I both associate with the North of England, and which gives the book an obsessive tone that is never quite shaken off. It works with the very young: "When Morris had drawn a face on the window, he would often pretend it was the face of someone he knew, and he would kiss the lips over and over again, saying 'How do you do? Pleased to meet you. Have a cup of tea'," but by the end of the book the sad strain has grown self-conscious and therefore slack. There is a familiar drug 'trip,' written about so frequently that I already confuse it with fiction, and Cook joins the swim with a 'stream of consciousness' which has ruined every novel since the early 'forties. These conventional themes are too contrived, and unbalance what is otherwise a fresh and free-ranging novel.

The Sightseer is back amongst the good old boys, a novel devoted to 'I' or 'me' or how I grew to love myself by becoming a character. 'I' is Caleb Sharrow, one of those solemn young Americans who imagine they are doing something for Art when they keep a diary; he is a "movie-maker" and has a camera like other people have Alsatians. He also says things like We movie-makers speak of cinema verite," as dull people will, and talks in what seems to me to be a breathless manner of "my metaphysical days."

It may be that Geoffrey Wolff is playing a nice literary trick, and knowingly makes Caleb the little prig he is in order to warn us of the perils of American life; if this is the case, Wolff has forgotten that brevity is the form, if not the soul, of wit. But the novel's prose is certainly as Prolix and as self-indulgent as its hero, and I suspect Wolff wants himself and his Caleb to be taken equally seriously. He uses a mannered and quasi-lyrical style, pitched somewhere between early Joyce and late Harold Robbins, Which cannot be sustained for very long Without my law of diminishing interest coming into effect. And when Caleb says at one point: "Ah childhood! Ah montage!" I knew I was in for a rough ride.

It just goes to show what a small world it is, since it was only in last night's soap-opera that I came across lines like "I knew then and the knowledge was an illumination, fierce, cruel, bracing." And when a girl is "at once fragile and Opaque," you know at once that she is mysteriously foreign and that Caleb will say, again breathlessly, "You dance wonderfully,' I said to her, 'you are very beautiful'." But it ,does come as something of a surprise when 'I' and 'me' turn out to be "very beautiful" too. Since 'I' in this case bears no relation to the rather hirsute American on the dust-jacket, I can only assume that Mr Wolff has been indulging in some common-or-romance wish fulfilment. But fantasy can sometimes go Where no one will wish to follow.

Previous page

Previous page