Why did no one send off the clowns?

Christopher Hitchens

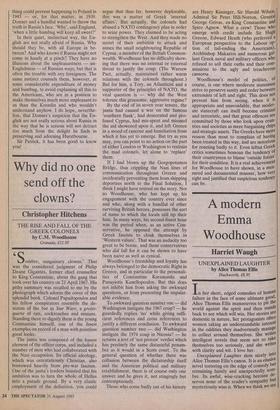

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GREEK COLONELS by C.M. Woodhouse Granada, £12.95 Sombre, sanguinary clowns.' That was the considered judgment of Philip Deane Gigantes, former chief counsellor to King Constantine, about the gang that took over his country on 21 April 1967. His pithy summary was recalled to me by the photograph which adorns the cover of this splendid book. Colonel Papadopoulos and his fellow conspirators resemble the de- nizens of the bar in Star Wars; a grotes- querie of rats, cockroaches and simians. Standing there to dignify them is the young Constantine himself, one of the finest examples on record of a man with pointless good looks.

The junta was composed of the basest element of the officer corps, and included a number of men who had collaborated with the Nazi occupation. Its official ideology, which was ostentatiously Christian, also borrowed heavily from pre-war fascism. One of the junta's leaders boasted that his ambition was to turn the whole, of Hellas into a parade ground. By a very elastic employment of the definition, you could argue that thus far, however deplorable, this was a matter of Greek 'internal affairs'. But actually, the colonels had abused a NATO contingency plan in order to seize power. They claimed to be acting to strengthen the West. And they made no secret of their ambition to attack and annex the small neighbouring Republic of Cyprus, a member of the British Common- wealth. Woodhouse has no difficulty show- ing that there was no internal or external threat to justify the coup. (The Warsaw Pact, actually, maintained rather warm relations with the colonels throughout.) But for him, a Tory, an Atlanticist and a supporter of the principles of NATO, the vital question is — why did the West tolerate this gruesome, aggressive regime?

By the end of its seven year tenure, the junta had caused a war on the famous `southern flank', had desecrated and pro- faned Cyprus, had mis-spent and misused the aid showered upon it, and left Greece in a mood of rancour and humiliation from which it has yet to emerge. But try as you may, you can point to no action on the part of either London or Washington to restrain the mad colonels, let alone to 'replace' them.

If I had blown up the Gorgopotamos Bridge, thus crippling the Nazi lines of communication throughout Greece and incidentally preventing them from shipping deportees north to the Final Solution, I think I might have retired on the story. Not so Woodhouse, who has kept up, his engagement with the country ever since and who, along with a handful of other surviving British heroes, possesses the sort of name to which the locals still tip their hats. In many ways, his second-finest hour was the period when, as an active Con- servative, he opposed the attempt by Greek fascists to cloak themselves in `Western values'. That was an audacity too great to be borne, and those conservatives who did fall for it can be shown to have been naive as well as cynical.

Woodhouse's friendship and loyalty has always belonged to the democratic Right in Greece, and in particular to the personali- ties of Constantine Karamanlis and Panayiotis Kanellopoulos. But this does not inhibit him from asking the awkward questions, or from presenting the unpalat- able evidence.

To awkward question number one — did Washington instigate the 1967 coup? — he guardedly replies 'no' while giving suffi- cient references and cross references to justify a different conclusion. To awkward question number two — did Washington instigate the 1974 coup in Nicosia? — he returns a sort of 'not proven' verdict which has precisely the same distasteful penum- bra as it would in a Scots court. To the general question of whether there was collusion between the dictatorship itself and the American political and military establishment, there is of course only one answer and he gives it, not stingingly but contemptuously.

Those who come badly out of his history are Henry Kissinger, Sir Harold Wilson, Admiral Sir Peter Hill-Norton, General George Grivas, ex-King Constantine and Spiro Agnew. What a crew! Those who emerge with credit include Sir Hugh Greene, Edward Heath (who preferred a European perspective to the Labour op- tion of tail-ending the Americans), Archbishop Makarios and numerous gal- lant Greek naval and military officers who refused to sell their oaths and their com- missions to the ugly and treacherous camorra.

Woodhouse's model of politics, of course, is one where moderate statesmen strive to preserve sanity and order between extremists of left and right. This does not prevent him from seeing, when it Is appropriate and unavoidable, that moder- ate statecraft can itself become criminal and terroristic, and that great offences are committed by those who look upon coun- tries and societies as mere bargaining chips and strategic assets. The Greeks have more reason than most to complain of having been treated in this way, and are notorious for reacting badly to it. Even leftist Greek critics sometimes bemoan the tendency of, their countrymen to blame 'outside forces for their condition. It is a real achievement for Woodhouse to have shown, in a mea- sured and documented manner, how very right and justified that suspicious tendency can be.

Previous page

Previous page