Screen •History

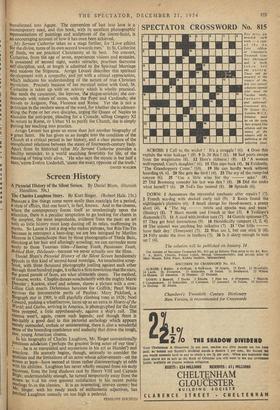

The Charles Laughton Story. By Kurt Singer. (Robert Hale. 15s.) PERHAPS a few things come more easily than nostalgia for a period, a state of affairs, that one hasn't, in fact, known. And in the cinema, Where the contemporary forces itself so unrelentingly upon the attention, there is a peculiar temptation to go looking for charm in the simplest, the most improbable, evidence from the past: an art With so little history must keep dusting off its relics, reaffirming its myths. So Lassie is just a dog who makes pictures, but Rin-Tin-Tin becomes in retrospect a hero-dog; we are less intrigued by Marilyn Monroe in CinemaScope than by those photographs of Theda Bare, Clutching at her hair and alluringly scowling; we can surrender more easily to those Twenties titles-Flaming Youth, Passionate Youth, Bobbed Hair, Deelassee-because we never actually saw the films. Daniel Blum's Pictorial History of the Silent Screen handsomely appeals to this kind of second-hand nostalgia. An unselective scrap- book, with three thousand photographs jostling against each other through three hundred pages, it reflects a firm conviction that the stars, the grand parade of faces, are what ultimately count. The method, Of course, works. Chaplin dances nonchalantly with the mighty Mario bressler ; Keaton, aloof and solemn, shares a picture with a cow; Lillian Gish enacts Dickensian heroines for Griffith; Pearl White survives the innumerable perils of Pauline; Mary Pickford, a biograph star in 1909, is still playfully climbing trees in 1926; Noel Coward, pushing a wheelbarrow, turns up as an extra in Hearts of the World; and Garbo, arriving in America, is photogimphed for the first time propped, a little apprehensively, against a ship's rail. The c, inema won't, again, create such legends; and though there is Inevitably a good deal in this pictorial anthology which appears merely outmoded, archaic or uninteresting, there is also a wonderful sense of the bounding confidence and audacity that drove the tough, raw, young American cinema. In his biography of Charles Laughton, Mr. Singer conventionally ombines adutution ('perhaps the greatest living actor of our time'; • • . . he is as manysided and mysterious in his art as Hamlet') and anecdote. He scarcely begins, though, seriously to consider the qualities and the limitations of an actor whose achievements-on the screen at least-have seemed at times rather disconcertingly at odds With his abilities. Laughton has never wholly escaped from nis early ttecesses, from the long shadows cast by Henry VIII and Captain uligh; understandably enough, he turned temporarily away from the Sereen to ti.)d his own greatest satisfaction in his recent public rte.adings frvin the classics. It is an interesting, uneven career; but 'W. Singer, with his ready stock of enthusiastic adjectives, has Perched Laughton uneasily on too high a pedestal.

Previous page

Previous page