CHESS

We must think again

Raymond Keene

A NEW BOOK by international master Byron Jacobs, Analyse to Win: Visualising Victory (Batsford, £14.99), makes the fasci- nating point that all analysis of complicated positions provided by elite grandmasters and world champions is possibly open to suspicion if it was prepared before the last three years or so.

It is only during the last few years that computer-assisted analysis, whether of the mainframe or PC variety, has enabled ana- lysts to double-check their conclusions to the point where they can be certain of 100 per cent accuracy. Before then, analysis, even by the greatest, may overlook tactical wrinkles which the human brain may find difficult but which are metaphorical meat and drink to computers. This is an enticing hypothesis which, in fact, throws open over a century of masterpieces by top players, dating from the MacDonnell–Labourdon- nais matches of 1834 right up to recent clashes between Kasparov and Karpov, as potential fields for reinterpretation. Established 'truths' may be overthrown and it is possible that the most extraordinary conclusions about well rehearsed jewels of the chessboard are yet to be discovered.

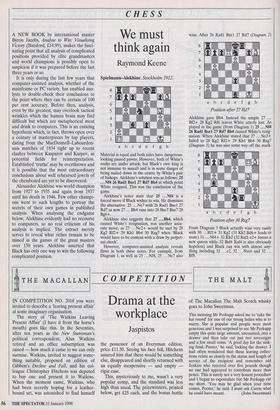

Alexander Alekhine was world champion from 1927 to 1935 and again from 1937 until his death in 1946. Few other champi- ons went to such lengths to portray the secrets of their own games in published analysis. When analysing the endgame below, Alekhine evidently had no recourse to computers, so no real criticism of his analysis is implied. The extract merely serves to reveal what riches remain to be mined in the games of the great masters over 150 years. Alekhine asserted that Black has only one way to win the following complicated position. Spielmann–Alekhine: Stockholm 1912.

Material is equal and both sides have dangerous- looking passed pawns. However, both of White's rooks are under attack, but Black's own king is not immune to assault and is in some danger of being nailed down in the centre by White's pair of bishops. Alekhine's solution was as follows: 25 ...Nf4 26 Radl Bxel 27 Rd7 Bb4 at which point White resigned. This was the conclusion of the game.

Alekhine's notes state that 25 ... Nf4 is a forced move if Black wishes to win. He dismisses the alternative 25 Ne7 with 26 Radl Bxel 27 Rd7 as now 27 ... Bb4 runs into 28 Bxe7 Bxe7 29 Bg6+.

Alekhine also suggests that 27 ...Bb4, which caused White's resignation, was another accu- rate move, as 27 ... Ne2+ would be met by 28 Kg2 Rf2+ 29 Khl Bb4 30 Rxg7 when 'Black would have to be content with a draw by perpet- ual check'.

However, computer-assisted analysis reveals flaws in both these notes. For example, from Diagram 1, as well as 25 ...Nf4, 25 ...Ne7 also wins. After 26 Rad1 Bxel 27 Rd7 (Diagram 2)

Position after 27 Rd7

Alekhine gave Bb4. Instead the simple 27 ... Bf2+ 28 Kg2 Rf6 leaves White utterly lost. As played in the game (from Diagram 1) 25 . Nf4 26 Radl Bxel 27 Rd7 15b4 caused White's resig- nation. When Alekhine stated that 27 ... Ne2+ failed to 28 Kg2 Rf2+ 29 Kh1 Bb4 30 Rxg7 (Diagram 3) he was also some way off the mark.

From Diagram 3 Black actually wins very easily with 30 ...Rfl+ 31 Kg2 (31 Kh2 Bd6+ leads to mate) 31 ...Nf4+ 32 Kh2 (32 Kxfl e2+ forces a new queen while 32 Bxf4 Rxf4 is also obviously hopeless) and Black can win with almost any- thing including 32 ... e2, 32 ... Nxe6 and 32 ... Bf8.

Previous page

Previous page