ANNIVERSARY: THOMAS GRAY DIED JULY 30, 1771

Elegy written in St. Peter's churchyard Burnham, Sunday, August 28, 1737

PETER WATSON-SMYTH

ON July 30, 1771, Thomas Gray died at the age of fifty-four, leaving behind a small, rich collection of poems and letters, the reputation of having been possibly the most 'learned man in Europe of his time and one of the classic mysteries of literary history: where, when and why did he come to write "the best-known poem in the English language," his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard?

So many theories have been advanced by scholars on each of these separate questions over the past two centuries that it may seem arrogant for a mere laymandetective to claim to be able to prove a comprehensive solution to the whole mystery beyond all reasonable doubt, but that I shall attempt within ,the confines of this short article.

It is generally accepted that the original Elegy consisted of the present first eighteen stanzas, with little alteration, plus four at the end which Gray much later discarded when he decided to lengthen the Poem before sending the result to Horace Walpole from Stoke Poges on June 12, 1750, saying: "1 have been here at Stoke a few days.... and having put an end to a thing, whose beginning you have seen long ago, I immediately send it to you. You Will, I hope, look upon it in the light of a thing with an end to it" — and he went O n to cover this cryptic remark with a Contrived, But typical wry joke against himself.

This first appearance of the Elegy, being one of the very few axioms in the mystery, demands our close attention. What did that odd remark mean? Why did he send the poem " immediately " to Walpole rather than to his publisher or any other friend? Why had he decided to alter and lengthen the poem? Why was he so annoyed when Walpole, admiring the poem, passed it round so many of his friends that he, Gray, was forced to arrange its publication? Why, even then, did he beg Walpole to get the printer to say that the poem had come into his hands by accident?

These are all important questions, but there is one more important still. The Elegy was an instant success, making the little known Gray a celebrity almost overnight. In the twenty years that remained to him he must often have been asked where, when and why he had written it, yet it appears that he took these secrets deliberately to the grave. Why?

If we examine the "'long ago" first, we know at once that Gray could not have been referring to any time between March 1739 and November 1746. This is because he embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe with Walpole on the former date, quarrelled bitterly with him at Reggio in 1740 and was never again on speaking terms with him until a reconciliation was arranged through a friend on the latter date. Would "'long ago" have been less than four years (we can show that the Elegy was first written in late summer) or more than eleven? Let us look at their relationship before the break.

Gray's two best friends at Eton were Horace Walpole and the poet Richard West, the former the wealthy son of the Prime Minister of England and the latter the son of the Lord Chancellor of Ireland; together with Thomas Ashton, this coterie of weakly, intellectual boys were known throughout the school as the Quadruple Alliance. Unlike his two best friends, however, Gray was of humble birth, the penniless son of a City scrivener and a milliner, lucky to be alive at all as he was the fifth of their twelve children and the only one to survive infancy. So cruel and mean was his father to his mother that she sent him at the age of eight to be brought up by her brother, Robert Antrobus, a Fellow of Peterhouse and a tutor at Eton, who lived at nearby Cant's Hill, Burnham. Antrobus, according to Walpole, "took prodigious pains" with his young nephew, particularly training him to be a keen and accurate student of Nature; a -• discipline which Gray retained throughout his life, even to the extent of noting in his diary the precise dates upon which he first heard each new birdsong. Unfortunately Robert Antrobus died when Gray was only thirteen, leaving his house at Burnham to another sister, Anna, who thereafter lived there with her husband, Jonathan Rogers, a retired solicitor. Although it appears that Gray often stayed there between terms right up to his early years at Cambridge, it is clear that he had little affection for his aunt and uncle.

As Gray was, like Walpole, particularly devoted to his mother, it will surprise no psychiatrist that such a background produced a homosexual whose first and greatest love, I believe, was Horace Walpole. That love, I further believe, was at first reciprocated and led, somewhere in Gray's late teens, to the original version of the Epitaph as his first poem in English, written as an imaginary epitaph on himself. If so, of course, the poet of the latter part of the Elegy proper must also be Gray himself and this we can establish by comparing the poem's description with Gray's life at Cant's Hill and with the local topography which, although barely twentyfive miles from central London, has hardly changed at all since Gray's youth. Haply some hoary-headed Swain may say, 'Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn 'Brushing with hasty steps the dews away 'To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.

'There at the foot of yonder nodding beech 'That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high, 'His listless length at noontide wou'd he stretch, 'And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

'Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn, 'Mutering his wayward fancies he wou'd rove, 'Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn, 'Or craz'd with care, or cross'd in hopeless love.

'One morn I miss'd him on the custom'd hill, 'Along the heath and near his favtrite free; 'Another came; nor yet beside the rill, 'Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he, In August 1736 Gray wrote to Walpole from Cant's Hill saying that he was obliged to write standing up as his uncle's dogs took up every chair in the house and that his uncle despised him for "walking when I should ride and reading when I should hunt." His "comfort amidst all this" was Burnham Beeches, half a mile distant down a green lane: "A forest all my own. . . . covered with most venerable beeches.. .. that... are always dreaming out their old stories to the wind And as they bow their hoary tops relate In murm'ring sounds, the dark decrees of fate; While visions, as poetic eyes avow, Cling to each leaf and swarm on every bough.

"At the foot of one of these squats Me, I (ii penseroso) and there grow to a trunk for a whole morning. . . . In this situation I often converse with my Horace, aloud too, that is talk to you...." The similarities with the habits of the poet described in the Elegy are striking enough and are made more so if we add back the stanzas which Gray finally omitted, particularly: Him have we seen the green-wood side along While o'er the heath we hied, our labours done, Oft as the woodlark piped her farewell song With wistful eyes pursue the setting sun and then look at the topography of the walk from Cant's Hill (now the Burnham Beeches Hotel) to that spot by the Swilly stream in Burnham Beeches which is still marked on some maps as Gray's Tree.'

The site of the Rogers's house, now vanished, lies near the bottom of a shady hollow in the grounds of what is now the Burnham Beeches Hotel. If one repeats Gray's dawn walk to his favourite tree today, one first heads north up a fairly steep hill — then a grassy lane, but now tarmac; near the top one passes a small wood on the right which the lane swings round so that one reaches the flat fields (upland lawn) facing due east and it is here that one first meets the rising sun. These fields reach up to the Beeches themselves and to the left of the lane lies the Burnham Beeches Golf Course (heath). 'Gray's Tree' is only a little way inside the Beeches and the whole walk is barely three quarters of a mile. Woodcutters returning to Burnham village would have walked directly across the " heath " and would have seen Gray walking westward alongside the wood at the top of the hill on his way home.

While establishing that Gray himself is the " poet " of the Elegy and that he is referring to the Cant's Hill period of his life (i.e., pre-1738) is the vital point so far, I must here point out that the letter also (a) confirms that he was unhappy with the Rogerses at Cant's Hill, (b) shows how near-impossible it was for him to write or compose indoors there and (c) shows that it was to Walpole that he muttered his wayward fancies; a fact which, in turn, helps to identify Walpole as the " Friend " of the Epitaph and the object of the "hopeless love."

Now all this refers to the much 'later additions to the original Elegy and the considerable time gap indicated by the "long ago" in the Walpole letter is echoed again in one of the finally-omitted stanzas where he clearly refers to his favourite tree as Thy once-loved haunt, this long deserted shade.

Nevertheless, the positive identification of locality and period makes the identification of the Churchyard simplicity itself. St. Peter's, Burnham, lies less than a mile from Cant's Hill and was the parish church. Both Robert Antrobus and Jonathan Rogers (although he had moved to Stoke Poges some two years before he died) are buried there. That the latter was a loyal parishioner is further attested to by his memorial tablet which tells us in Latin, by the sly hand of Gray, that "he devoted the last years of his life to himself, his friends and God."

THE Curfew tolls the knell of parting day, • The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea, The plowman homeward plods his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight, And all the air a solemn stillness holds, Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight, And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds; Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow'r The mopeing owl does to the moon complain Of such, as wand'ring near her secret bow'r, Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade, Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring heap, Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude Forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

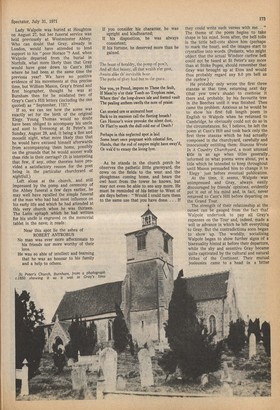

Now steepled, St Peter's then was as in the c.1850 photograph below. If one stands at its porch today and looks south across the old graveyard one can still, in winter, see the tower of Burnham Priory just 300 yards away. This was a private house built in 1824, but believed to have been so named because of a ruined thirteenth century watchtower (built by Richard, Duke of Cornwall, who founded Burnham Abbey) which previously stood on the site; a much more likely haunt of owls than any bell-ridden church tower which, in any case, could never have been " yonder " to the accurate Gray in the tiny country

churchyards of those days. The implication that the poet was on high ground is borne

out by the fact that St Peter's, unlike Stoke Poges, is so situated with what were then rolling leas falling away to the west of the Churchyard, but are now, unfortunately, modern houses. Also unlike Stoke Poges, St Peter's churchyard has always had its elms as well as yews..

Why, then, have its claims been ignored for so long? Mainly because of a false axiom, accepted as much by Gray's friends and contemporaries as by almost all subsequent scholars, that he never composed any original English verse before 1742. Thus because, with the sole exception of Jonathan Rogers's funeral in November 1742, there was no evidence that he ever revisited St Peter's after his return from abroad, it has always been ruled out. It may also have been felt that; as a 1740 census showed the parish to contain "570 souls and no Papist," it was too big for a hamlet, but this is to ignore (a), that Gray's first word was " Village " and (b), that the rerouting of the Bath Road in Tudor times had caused much of the population to drift down a mile or so south, leaving the village proper with only about twenty houses, the size of a traditional hamlet.

The precise time of year when the Elegy was first written is also remarkably easy to determine thanks to Gray's uncanny observation and accuracy. By carefully describing that short period of time when, on a fine night (the moon), dusk gives place to darkness, and timing this by his reference to the 8.0 pm curfew, he enables us to establish two periods as the only possibilities, for, on such nights, dusk turns to darkness at the end of what is scientifically known as Nautical Twilight. Under the Julian Calendar Nautical Twilight ended at, say, 7.50 pm on March 21 and August 28, but the spring period can be ruled out not only on grounds of inclement weather, but more positively by the flying stag beetle. Such creatures are practically never on the wing at that time, although common enough near elm stumps in late summer.

At this point it may seem that a case might be made out for August 1736 as the birthdate of the original Elegy, but this would leave unanswered the mystery of the 'Abbey references' in the poem which have troubled many scholars. What, though, if we look at last August 1737?

On August 22, 1737, we find Gray in London, writing to Richard West to thank him for an elegy in English (' Ad Amicos '), which West had sent him some six weeks earlier: " Low spirits," he writes, " are my true and faithful companions most commonly we sit alone together. Would I could turn them to the same use that you have done. . . . If they could write such verses with me, not hartshorn, nor spirits of amber, nor all that furnishes the closet of an apothecary's widow, should persuade me to part with them. But, while I write to you, I hear the bad news of LadY Walpole's death on Saturday night last. Forgive me if the thought of what my poor Horace must feel on that account obliges me to have done in reminding you that am, Yours, etc."

Lady Walpole was buried at Houghton on August 27, but her funeral service was held previously at Westminster Abbey. Who can doubt that Gray, already in London, would have attended to lend support to his "poor Horace "? And, when Walpole departed from the burial in Norfolk, what more likely than that Gray would have gone down to Cant's Hill where he had been at the same time the previous year? We have no positive evidence of his movements at this precise time, but William Mason, Gray's friend and first biographer, thought he was at Burnham then for he misdated two of Gray's Cant's Hill letters (including the one quoted) as "September, 1737."

If so, we can see how the scene was exactly set for the birth of the original Elegy. Young Thomas would no doubt have been obliged to accompany his uncle and aunt to Evensong at St Peter's on Sunday, August 28, and, it being a fine and moonlit night, what more likely than that he would have excused himself afterwards from accompanying them home, possibly on the grounds that he would sooner walk than ride in their carriage? (It is interesting that few, if any, other theories have provided a satisfactory reason for the poet being in the particular churchyard at nightfall.) Left alone at the church, and still impressed by the pomp and ceremony of the Abbey funeral a few days earlier, he may well have recalled the simple funeral of the man who had had most influence on his early life and which he had attended at this very church when he was thirteen. The Latin epitaph which he had written for his uncle is engraved on the memorial tablet in the nave; it reads : Near this spot lie the ashes of ROBERT ANTROBUS No man was ever more affectionate to his friends nor more worthy of their love.

He was so able of intellect and learning that he was an honour to his family and a help to others. If you consider his character, he was upright and kindhearted; If his disposition, he was always consistent; If his fortune, he deserved more than he gained.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r, And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave, Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Nor you, ye Proud, impute to These the fault, If Mem'ry o'er their Tomb no Trophies raise,. Where thro' the long-drawn isle and fretted vault The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

Can storied urn or animated bust Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath? Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust, Or Flatt'ry sooth the dull cold ear of Death ?

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire, Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway'd, Or wak'd to extasy the living lyre.

As he stands in the church porch he observes the pathetic little graveyard, the cows on the fields to the west and the ploughman coming home, and hears the owl hoot from the tower he knows, but may not even be able to see any more. He must be reminded of his letter to West of six days before : "Would I could turn them to the same use that you have done. . . . If

they could write such verses with me... " The theme of the poem begins to take shape in his mind. Soon after, the bell tolls in the little bell-cote above him (perhaps to mark the hour), and the images start to crystallise into words. (Pedants, who might object that the actual Windsor curfew bell could not be heard at St Peter's any more than at Stoke Poges, should remember that Gray was brought up at Eton and would thus probably regard any 8.0 pm bell as the curfew.) He probably only wrote the first three stanzas at that time, returning next day (that yew tree's shade) to continue it there and, probably, by his favourite tree in the Beeches until it was finished. Then came the problem. Anxious as he would be to show his first full length poem in English to Walpole when he returned to Cambridge, he obviously could not do so in the circumstances. So, I believe, he left the poem at Cant's Hill and took back only the first three stanzas which he had actually composed in the churchyard, carefully and innocuously entitling them: Stanzas Wrote In A Country Churchyard, a most unusual title in an age when titles generally.. informed on what poems were about, yet a title which he intended to keep throughout until Mason persuaded him to change it to 'Elegy' just before eventual publication.

At the time, it seems, Walpole was unimpressed and Gray, always easily discouraged by friends' opinions, evidently put it out of his mind and, in fact, never returned to Cant's Hill before departing on the Grand Tour.

The strength of their relationship at the outset can be gauged from the fact thaf Walpole undertook to pay all Gray's expenses on the Tour and, indeed, made a will in advance in which he left everything to Gray. But the contradictions soon began to show up. The worldly, socialising Walpole began to show further signs of a bisexuality hinted at before their departure, while the shy and sensitive Gray became quite captivated by the cultural and natural riches of the Continent. Their mutual jealousies came to a head in a bitter quarrel at Reggio which neither ever fully explained — for what seem to be obvious reasons if my theory is correct. The aftermath of the affair was Gray's astonishing output in the summer of 1742: the Ode on the Spring, the Eton Ode, the Sonnet on the Death of Richard West and the Hymn to Adversity — all full of nostalgia for his happy youth and adolescence, before the dream collapsed at Reggio.

True, after their reconciliation at the end of 1745, Walpole bought a house at Windsor in the summer of 1746 to be near Gray, who wrote to him in December of that year: "This comes du fond de ma celluile to salute Mr H. W., not so much him that visits and votes, and goes to White's and to Court, as the H.W. in his rural capacity, snug in his tub on Windsor Hill and.... him that can slip away, like a pregnant beauty (but a little oftener), into the country, be brought to bed perhaps of twins, and whisk to town again the week after with a face as if nothing had happened."

But they evidently soon realised that the magic had gone forever. Gray retreated to an ivory tower life at Cambridge while Walpole threw himself into his life's work of creating Strawberry Hill.

So it went until, in November 1749, Gray's favourite Aunt Mary died and was buried at Stoke Poges. Amongst her papers, I believe, were found the Epitaph and the original Elegy which had fallen into her hands when the family moved from Cant's Hill to Stoke Poges while Gray was abroad and which she had innocently retained as mementoes of her beloved nephew's adolescence. The effect on Gray of this sudden discovery of his first two poems in English, which he had long believed lost and which were his only compositions to predate his break with Walpole, can readily be imagined. I believe that he resolved to knit them tqgether into a poem that would serve as an epitaph both to his adolescence and to his affair with Walpole and one in which the nostalgia would be tempered by the fact that he now well knew the inevitable tragedy and hopelessness of his position as a homosexual. This he did at Cambridge in the winter of 1749-50, finishing it at Stoke Poges (or nearby Burnham Beeches) in early June 1750, before sending it as a private poem to the one man for whom it was meant. But Walpole missed the hints in the letter and passed the poem around his friends, thus forcing Gray to publish it against his will. Henceforward all he could do to protect its essential privacies was to refuse to disclose where, when or why he had written it and, indeed, never to deny the accepted view that he had never composed in English before 1742. Thus Gray himself has been largely responsible for the endurance of the mystery for so long.

But did Walpole ever realise the inner meanings of the Elegy? There is evidence that he eventually did for, when Mason wrote to him after Gray's death saying that he was "inclined to believe " that the Elegy was "begun if not completed" about the time of West's death (June 1742); Walpole wrote back that he was " sure " that he had had the "twelve or more first lines" from him at least three years later. Mason's reply, unfortunately, is lost to us, but evidently contained an incontrovertible fact which made Walpole's position untenable for, in his reply, he tamely withdrew his assertion and in his later preface to Gray's Works, he goes along with Mason's guess, albeit without support or enthusiasm. Yet Walpole knew that Mason's guess was impossible for he could never have seen the beginning except before the Grand Tour or after November 1745. Did he keep quiet because the penny had dropped? And did he do so to protect his own reputation or that of Gray?

That completes my reconstruction which, I submit, alone answers all the questions involved in the mystery, but, before closing the case, perhaps I should deal with two possible objections, one technical and one more fundamental. The former concerns the ninth stanza of the final Elegy which obviously echoes one of West's which was not written until December 1737. This clearly dates from the 1749-50 revision period, for Gray, though a plagiarist in the Elegy, was too honest to be a conscious one; West, therefore, must have been dead a long time for his lines to have slipped into Gray's subconscious to be revived again as his own. This, in fact, is supported by the Pembroke MS, which shows that the first couplet of the tenth stanza was the only major revision by Gray after the first publication — presumably because he saw that it no longer followed properly from the altered ninth.

The more fundamental objection might be that raised by the late R. W. KettonCremer, a noted authority on and biographer of Gray, who wrote at an early stage in my researches: " Every line of the Elegy shows such extraordinary accomplishment and maturity that I cannot believe that it was, so to speak, his maiden effort (in English verse)".

Yet Gray had written some excellent Latin poems and English translations before the date I claim for the original Elegy and is it any easier to accept that extraordinary summer flush of 1742 as his maiden efforts? But let us hear Horace Walpole himself speaking of West and Gray in their early youth in his letter to Mason of November 27, 1773: "They not only possessed genius . . . but both had abilities marvellously premature. What wretched, boyish stuff would my contemporary letters to them appear if they existed." Trenchant evidence from one of the greatest letter-writers of all time, who goes on to say : "Forgive me, but I cannot think Gray's Latin poems inferior even to his English."

And hear him again to Lord Lyttleton (July 25, 1777): "I do not think they (Gray's contemporaries) ever admired him except in his Churchyard, though the Eton Ode was far its superior and is certainly not obscure. The Eton Ode is perfect."

We may wonder whether Walpole meant that the Elegy was obscure to him or to others, but it is clear that, judging them by the critical standards of his time, he was in no doubt that The Eton Ode represented a considerable advance on the Elegy.

Finally let us remember the similarities of that lone stanza in his letter from Cant's Hill (a stanza much admired and quoted by Hazlitt, incidentally) with those of the Elegy: quatrain, pentameters, beech trees, poetic maturity — and then ask ourselves why, if West could write a beautiful Elegy in English in June 1737, Gray could not do likewise in August and September.

There my case rests. If it has been proved, as I submit, beyond all reasonable doubt and we are now to accept for the first time that what Palgrave described as " perhaps the noblest stanzas in our language" were largely written by a homosexual youth of only twenty as his first major attempt at English verse, it may be time, at this bicentenary of his death, for someone more qualified than I to make a reassessment of that strange character and prodigy that was Thomas Gray.

Previous page

Previous page