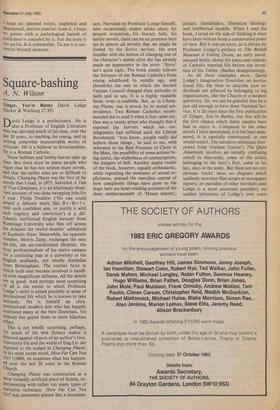

Square-bashing

A. N. Wilson

Ginger, You're Barmy David Lodge (Seeker & Warburg £7.95) Ginger, You're Barmy David Lodge (Seeker & Warburg £7.95)

David Lodge is a perfectionist. He is also a Professor of English Literature Who has devoted much of his time, over the last 20 years, to teaching the young, and to Writing somewhat impenetrable works of criticism. He is a believer in Structuralism. He is a Roman Catholic.

These hobbies and hobby-horses take up time. But there must be many people who regret that he has not written more novels, and that the earlier ones are so difficult to Obtain. Changing Places was the first of his novels that I read, in 1975. Subtitled A Tale Of Two Campuses, it is an hilariously obser- vant account of two dons swopping jobs for a Year. Philip Swallow (`No one could award a delicate mark like B + /B +? + With such confident aim, or justify it with such cogency and conviction') is a dif- fidently ineffectual English lecturer from Rummage University who flies off across the Atlantic for twelve months' sabbatical at Euphoric State. Meanwhile, his opposite number, Morris Zapp, exchanges the easy sex-life, the air-conditioned libraries, the busy professionalism of his native campus for a confusing year at a university in the English midlands, not wholly dissimilar from Birmingham. The routine farce in Which both men become involved is handl- ed with magnificent deftness. All the details are so good. And perhaps most surprising of all is the extent to which Professor Lodge's satire is aimed precisely at areas of Professional life which he is known to take seriously. He is himself an ultra- Professional modern don who has happily embraced many of the New Doctrines. Yet nobody has guyed them to more hilarious effect.

This is not wholly surprising, perhaps, for much of the best literary malice is directed against objects of an author's love. University life and the world of Eng.Lit. are exposed to the scalpel in Changing Places. In his most recent novel, How Far Can You Go? (1980), he examines what has happen- ed over the last 20 years in the Roman Church.

Changing Places was constructed as a most formally artificial piece of fiction, ex- Perimenting with rather too many types of narrative technique. How Far Can You Go? was presented almost like a documen- tary. Narrated by Professor Lodge himself, who occasionally makes asides about his present avocation, his literary fads, his earlier novels, there can be no pretence here (as in almost all novels) that we might be fooled by his fictive devices. He even doodles with the notion of changing one of the character's names after she has already made an appearance in the story. 'Story' isn't quite right. The book simply follows the fortunes of ten Roman Catholics from young adulthood to middle age, and chronicles the way in which the Second Vatican Council changed their attitudes to faith and to sex. It is a highly readable book: even re-readable. But, as in Chang- ing Places, one is struck by its moral am- bivalence. Two Roman Catholics recom- mended me to read it when it first came out. One was a trendy priest who thought that it exposed the horrors which his cor- religionists had suffered until the Liberal Revolution: 'You know, people really did believe those things', he said to me, with reference to the Real Presence of Christ in the Mass, the possibility of some actions be- ing sinful, the wickedness of contraception, the dangers of hell. Another papist reader of the book, however, equally enthusiastic, while regretting the moments of sexual ex- plicitness, praised the merciless exposé of how completely things have gone to the dogs: here are heart-rending accounts of the sheer embarrassment of 'House masses', guitars, handshakes, liberation theology and intellectual muddle. When I read the book, I erred on the side of thinking it must have been written from a conservative point of view. But it was an error, as is shown by Professor Lodge's ,preface to The British Museum is Falling Down, an early novel, reissued lately, about the pains and comedy of Catholic married life before the inven- tion of the Tablet. (Rather disappointing).

As all these examples show, David Lodge's imagination flourishes on institu- tional life. He likes to describe how in- dividuals are affected by belonging to big organisations, like the Church or a modern university. So, we can be grateful that he is just old enough to have done National Ser- vice. It is 20 years since the first publication of Ginger, You're Barmy, but this will be the first chance which many readers have had to enjoy it. Compared to the other novels I have mentioned, it is the least man- nered. It is carefully constructed, as one would expect. The narrative technique (bor- rowed from Graham Greene's The Quiet American) involves an initially confusing switch in time-scale, some of the action belonging to the hero's first, some to his last, days in the army. But there are no very obvious 'tricks' here: no chapters which suddenly turn into film scripts or newspaper reports; no parodies of other novelists (and Lodge is a most uncertain parodist); no sudden intrusions of Lodge's own voice

quoting letters from fans, professorially reproducing their errors of grammar. This, on the contrary, is a straight comic novel in the high English manner, and it compares rather well with the army tales of Jocelyn Brooke, Anthony Powell or Simon Raven.

Perhaps its comparative simplicity deriv- ed in part from a simplicity of attitude in the author. With universities and the Church of Rome, he evidently enjoys a rela- tionship of love-hate. With the army, the love element, if felt, has been cleverly eliminated. At the end of his 'hellish two years, the narrator, Jonathan Browne, reads a newspaper leader which says that 'Some substitute must be found which will have the same beneficial effects of character-training as National Service'. 'Mentally I phrased a reply: I think it will be difficult to find a substitute which will in- culcate bad habits, bad language, idleness, slothfulness, drunkenness and the amiable philosophy of "I'm all right Jack" as suc- cessfully as National Service'.

That is the unashamed viewpoint from which the yarn is told. Jonathan Browne and Mike Brady have been at London University together, and get drafted into the Royal Armoured Corps. The difference of attitude between the two men is melodramatically drawn. Jonathan decides, in effect, to 'sit it out'. He hates the coarseness of atmosphere and the time devoted to blanco, boot-polish and square- bashing, which could have been spent

reading Empson's Seven Types of Ambigui- ty. Having a chip on his shoulder about social differences, he refuses to try for a

commission, because he hates the blimpish toffs who, in his imagination, compose the officer class. But he does end up with quite a cushy job, and the rank of corporal.

Mike, a fiery Irish Catholic, reacts to it all less astutely. In particular, he is outraged by the cruelty of the corporal to a poor holy idiot called Percy Higgins, whose combina- tion of childishness and misery leads to a horrifying accident. Brady takes his revenge: on the corporal, on the army and, for blood will out, on the English. In the course of these adventures, Jonathan has

stolen Mike's rather agreeable girl-friend and at the end, though agnostics, they find

themselves in the position of a typical Lodge married couple: the wife vaguely cheesed off; the husband struggling to com- pose fiction and at the same time to further his academic career; a baby, who has arriv- ed in the world sooner than anyone hoped, 'sitting on his pot beside me as I write'.

David Lodge is a writer who not only takes views, but is interested in ideas. This is a pity, not merely because the views are sometimes unpalatable (reading this novel on July 19, for instance, I was unable to find the I.R.A. conscript a misguided but fundamentally lovable rogue; unable to feel pleasure that there was Guinness waiting for him on the table when he came out of prison; unable, more generally, to respond to the notion that all officers or speakers of Received Standard were necessarily pom- pous twits) but because it is a waste of a novelist's energy to have ideas. All one remembers from good novels is the extent to which they have believably captured human character, or been able to describe emotions, places and things. One only remembers the 'ideas' of really bad novels. David Lodge's novels are so re-readable, not because they are as clever as Roland Barthes but because they are as observant (at their best) as Kingsley Amis .

Ginger, You're Barmy did not entirely shake my rather wistful regret at being too young to have done National Service. But although I have missed this excellent oppor- tunity of being toughened up and acquiring moral fibre at the State's expense, I feel I know exactly what it was like to do Basic Training. This novel has all the ring of com- plete authenticity: the way the men spoke, their fears of having their leave cut short, the tedium, the physical hardship, the mingling of horror and farce are all brilliantly evoked. There must be lots of other novels about National Service. But even if there are, this must be the best.

Previous page

Previous page