Chosen for us

Stephen Logan

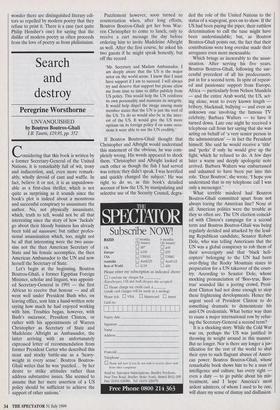

THE HARVILL BOOK OF TWENTIETH-CENTURY POETRY IN ENGLISH edited by Michael Schmidt Harvill, £20, pp. 728 C.S. Lewis said of the Bible that the more it was translated, the less it appeared to be read. A similar point might be made about poetry. The less it is read, the more it is anthologised. This is perhaps quite log- ical. When people are really interested in a subject, they tend to be knowledgeable about it and less in need of preliminary guidance. Anthologies offer such guidance and therefore abound when readers are most unsure of themselves. Though Michael Schmidt's anthology will be of interest to all poetry readers, it is perhaps chiefly aimed at those who are agnostic and diffident about modern poetry.

Readers who delight in the sheer diversi- ty of 20th-century poetry in English are richly catered for. The book contains 118 poets, (born between 1840 and 1970) of many nationalities and both sexes. It spans a broad stylistic range from the freewheel- ing extemporisation of the Beats to the cogitated elegance of Geoffrey Hill. Read- ers whose abiding question is not 'What poetry should I read?', but 'Why should I read poetry?' may, however, find the diver- sity confusing. There are no notes. This is usually defended on the grounds that the poems can be left to speak for themselves and that (in T.S. Eliot's phrase) poetry can Please take a seat...' communicate before it is understood. But T.S. Eliot was an exceptional reader; and the very facts which make anthologies nec- essary — namely, that poetry isn't popular and readers are diffident — make notes necessary too. Editors of poetry antholo- gies should be companionable to the extent that poetry is seen as austere.

We are long past the days when antholo- gies might be presented as neutral. Hence I disagree with Michael Schmidt about Larkin's Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century English Verse. He sees it as tending towards neutrality. I see it as highly opinionated. But maybe for Schmidt, neutral means complicit with an orthodox conception of tradition which I favour and he does not. Larkin likes the well-made accessible poem in which meaning has been squeezed out under pressure of formal exigencies. His heroes are Hardy and Betjeman. Schmidt is all for the Lawrentian pulse of life deter- mining its own form of verbal embodiment. For him, the exemplary poet is Pound. Both Schmidt and Larkin have produced personal anthologies. Which is to say, each of them has produced an anthology which expresses their conception of what poetry (not just 20th-century poetry) in English is.

The most transforming development in poetry this century was Modernism. Before it, modern poets were for the most part writing in a tradition which descended from Wordsworth (and hence, it should be added, from Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton, Wordsworth's own avowed mentors). These poets — such as W.H. Davies, Edmund Blundell and Walter de la Mare — wrote formally elegant, stylistically accessible poems, often (but by no means always) dealing with landscape and its spiri- tual associations. The Georgians were, how- ever, a variegated group. Some of them such as Edward Thomas — had personal experience of warfare and were subject to the influence of slightly older poets like Kipling or American ones like Frost. Even so, the best poems of all these poets exem- plified an art which was at once stringent and accessible. Modernism introduced a new form of stringency — one which affect- ed readers as much as writers — and acces- sibility was, in varying degrees, sacrificed.

What was really going on here was not an attempt to overthrow tradition, but an attempt to reinvigorate it. The Georgian manner was derided because it correspond- ed to habits of thinking and feeling which were no longer current. Pound, Eliot and their followers were seeking, as Dryden and Wordsworth had sought, to fashion a style of poetry which could accurately express current modes of experience. In the course of advancing their case, they exaggerated it. More damagingly still, the nuances of Eliot's critical pronouncements were too finely calibrated for easy recognition and were often ignored. The Modernists are often falsely assumed to be in favour of abandoning tradition, breaking metrical conventions and replacing sentiment with a severely intellectual impersonality.

But the radicalism of the Modernists was in fact deeply conservative. Pound thought it necessary 'to break the pentameter', but only as you break a horse. Eliot was much opposed to the idea that poetry is just prose that stops short of the right-hand margin. `Free' verse, he thought, could best be understood as either 'taking a very simple form, like the iambic-pentameter, and con- stantly withdrawing from it, or taking no form at all, and constantly approximating to a very simple one'. Hence his view that the most distinctive forms of originality often involved a minimal departure from tradi- tion. Thus when Schmidt endorses T.E. Hulme on metre, I think he risks promoting a view of conventions as 'merely' restrictive. This discourages readers from acquiring the knowledge — including knowledge of metre — on which an accurate appreciation of the art of poetry depends.

The widespread lack of interest in poetry Is, in my opinion, very largely a result of false ideas which were carried forward on a tide of pro-Modernist polemic. When the principles of an art aren't preserved within traditions which artists and their critics respect, public confusion follows.

Schmidt, in his introduction, distinguishes two traditions of modern poetry. He sug- gests that the rarefied one which includes Roy Fisher and Geoffrey Hill is of equal value to the popular one which includes Betjeman, Larkin and Seamus Heaney. In the 17th century this might have been an argument about Cleveland and Dryden. But though the impulse to treat every dedi- cated and accomplished poet with respect is good, the accompanying wish to level dis- tinctions of value among them is, in my view, unfortunate. It will not, in the long run, be vindicated; and in the shorter term it will not help new readers get a sense of why poetry matters. (Experienced readers Can of course look after themselves.) Schmidt is certainly no hectoring theorist; yet his anthology shows the influence of the intellectual climate of academic literary theory. Pluralism is safe, but it may none- theless be mistaken.

The self-consciously obscure, highbrow poem has all but killed poetry. Loss of knowledge of poetry as an art has affected readers and writers alike. Readers, because they no longer feel confident in judging a poem a non-poem. Writers, because they can't so easily tell when they are writing a non-poem (that is, a more or less porten- tous piece of randomly-lineated prose, which does not exploit the resources of poetic form). The music of poetry is what enables us to evade equally the barren intellectualism of the highbrow poem or the Jingling triviality of Poets Corner. My belief, which Schmidt probably does not share, is that the subtler forms of verbal melody can't be heard until the simpler forms have been heeded. In the meantime we have a melange of styles which some will call a triumph, others a sorry mess. No wonder there are distinguished literary edi- tors so repelled by modern poetry that they refuse to print it. There is a case (not quite Philip Hensher's one) for saying that the dislike of modern poetry as often proceeds from the love of poetry as from philistinism.

Previous page

Previous page