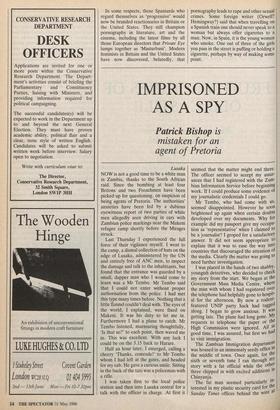

IMPRISONED AS A SPY

Patrick Bishop is

mistaken for an agent of Pretoria

Lusaka NOW is not a good time to be a white man in Zambia, thanks to the South African raid. Since the bombing at least four Britons and two Frenchmen have been picked up for questioning, on suspicion of being agents of Pretoria. The authorities' anxieties have been fed by a dubious eyewitness report of two parties of white men allegedly seen driving in cars with Zambian police markings near the Makeni refugee camp shortly before the Mirages struck.

Last Thursday I experienced the full force of their vigilance myself. I went to the camp, a dismal collection of huts on the edge of Lusaka, administered by the UN and entirely free of ANC men, to inspect the damage and talk to the inhabitants, but found that the entrance was guarded by a small, dapper man who I would come to learn was a Mr Tembo. Mr Tembo said that I could not enter without proper authorisation from the police. I had met this type many times before. Nothing that a little flannel couldn't deal with. The eyes of the world, I explained, were fixed on Makeni. It was his duty to let me in. Furthermore I had a plane to catch. Mr Tembo listened, murmuring thoughtfully, `Is that so?' to each point, then waved me in. This was excellent. With any luck I could be on the 3.15 back to Harare.

Half an hour later, I emerged, calling a cheery 'Thanks, comrade!' to Mr Tembo whom I had left at the gates, and headed for my cab. He gave a curious smile. Sitting in the back of the taxi was a policeman with a rifle.

I was taken first to the local police station and then into Lusaka central for a talk with the officer in charge. At first it seemed that the matter might end there. The officer seemed to accept my assur- ances that I had registered with the Zam- bian Information Service before beginning work. If I could produce some evidence of my journalistic credentials I could go.

Mr Tembo, who had come with us, seemed disappointed. However he soon brightened up again when certain doubts developed over my documents. Why for example did my passport give my occupa- tion as 'representative' when I claimed to be a journalist? I groped for a satisfactory answer. It did not seem appropriate to explain that it was to ease the way into countries that discouraged the attention of the media. Clearly the matter was going to need further investigation. I was placed in the hands of two shabby, youngish detectives, who decided to check my story from the start. We began at the Government Mass Media Centre, where the man with whom I had registered over the telephone had helpfully gone to hospit- al for the afternoon. By now a rodent- featured UNIP party hack had tagged along. I began to grow anxious. It was getting late. The plane had long gone. My requests to telephone the paper or the High Commission were ignored. All 19 good time, I was assured, but first we had to visit immigration. The Zambian Immigration departmen. t was housed in an immensely seedy office the middle of town. Once again, for the sixth or seventh time I ran through my story with a fat official while the othe r three chipped in with excited additions in Chinyanj a. The fat man seemed particularly in terested in my plastic security card for the Sunday Times offices behind the wire at Wapping. At the time of the move, all News International staff had been desig- nated 'consultant' when the passes were dished out, but the editorial workers had insisted on having this replaced by the title `journalist'. He pointed triumphantly at the Tippex mark blotting out the old designation. 'This card has been altered, Mr Bishop. How do you explain that?' `Well,' I began weakly, 'have you ever heard of a man called Rupert Murdoch?' Five minutes later I was sitting in a side office waiting to be taken to jail. As I was being led down to the car a small miracle occurred. I saw a young, white face on the stairs. 'Call the British High Commission- er!' I yelled. 'Tell him I've been arrested.' I just had time to gabble my name and paper before they took me away. Lusaka remand prison looks like a Foreign Legion fort, topped with rusty barbed wire. As the prison gates clanged behind me, the harmonious singing of the prisoners filled the twilight. The chief officer was kindly and intelligent and told me I would be all right. I seemed to have arrived in an oasis of sanity. I was put in a cell with 13 others, all convicts who worked seven days a week from dawn to dusk, cooking and serving the meals of the remand prisoners. They gave me cigarettes and offered dagga, made me a space on the concrete floor and shared their evening meal of bread and tea. It was the best accommodation in the jail, I was assured. The rest were herded in a hundred to a cell. Their leader was a handsome 37-year-old, Robert Musole, who ruled the cell with benevolent disci- pline.

'I have done a very bad thing to be here,' he said. What, I wondered? Murder? Multiple rape? 'I was in the army. I stole three rifles and sold them.'

'What did you get?' 'Fifteen years, I was lucky. I could have been executed.'

The rest of them were guilty of similar offences: Nixon, a year for stealing a suitcase, Snake, a year for stealing a tyre. A few hours later as we lay smoking and chatting there was a whispered conversa- tion between Robert and a warder at the cell window. 'Don't worry,' he told me. 'You're going to be released.' The anonymous young man on the stairs, an American, had been as good as gold and gone for help immediately. The High Commission, led by the delightful and energetic information secretary Mrs Maggie Cleaver, had thrown itself into action. The matter had been raised with Kaunda's office and a presidential decree issued. That night I slept in cotton sheets and a few days later I was home. I had been in prison less than five hours. Still being held at the time of writing, though, is a 22-year-old Briton whose only offence is to have a car with South African num- ber plates and a lot of exotic stamps in his passport.

Previous page

Previous page