A . 11 the paintings are a result of a crisis,'

says Frank Auerbach, who, famous for his early use of overwhelmingly thick paint and fanatical dedication to work, has become the epitome of the painter. The energy he injects into his work is a result of a frustration, 'more like an hysteria', at not being able to finish the painting. 'Unless one was conscious of the fact that life was short and one was going to die, there would be no sense in making this sort of effort.'

Auerbach's portraits are intimate. 'I have a clear idea', he narrates, 'of when I began to realise what I wanted to do as a painter. It was only after about five years of being a student [at St Martin's and then the Royal College]. I was living with someone, who has the initials E.O.W. I think she was the most important person in my life at the time. . . . The intensity of life with somebody and the sense of its passing has its own pathos and poignancy. There was a sense of futility about it and I just wanted to pin something down that would defy time so it wouldn't all just go off into thin air. This act of portraiture, pinning down something before it disappears, seems to be the point of painting. Our lives run through our fingers like sand, we rarely have the sense of being able to control them, yet a painting by a good painter, say by Manet, Hogarth or Velasquez repre- sents a moment of grasp and control of man over his experience. It makes life more bearable.' A. uerbach only paints people with whom he is familiar, yet he is not jesting when he says that the human aspect 'may be my own distraction at not being able to get it right. What I am thinking of consciously is largely geometry. I don't regard the paint- ing as finished till it is locked geometrically for me in a way I hadn't foreseen. I am not

Frank Auerbach

Painter in crisis

Alistair Hicks

trying to sway people or make a human appeal.' Nor did he 'set out to do anything particular with paint. Sickert said that the great oil painters were the people who had been brought up in the tradition of fresco and tempera. I know I'm totally deficient in that sort of training. I sometimes wonder if I had had a different training whether the look of the material might not have been different. On the other hand I do know that I'm impetuous, impatient and that the thing I value in painting is the element of surprise, of surprising myself. The look of my pictures is not conditioned by a pro- gramme but by getting into a state of despair at not being able to finish them.' Despite his protestations, Auerbach more than any other painter, appears to have a chemical reaction with the painting. His paintings are so consistent in vision and technique that it is now impossible to detach one from the other. His use of paint is one of the major influences on young British painters. It is a declaration of faith in the act of painting itself and in the easel, which for much of the last 30 years has been unfashionable. 'There is a point at which if one is pushing the paint in a certain way, it seems to drag you in its wake,' he says. 'The paint itself seems to breed images. I try to take the picture to the point where it seems to make itself. It doesn't have anything to do with the thickness, but there is a give and take between the picture and oneself. One picks up figures from the paintings and one tries to impose one's desires onto them.'

Bomberg's precise influence on Auer- bach has often led to controversy. Auer- bach himself is very clear on the subject. 'It wasn't a question of an idiom,' he says. 'Indeed when I read reports and descrip- tions of his approach now, I don't really recognise them.' Auerbach was fired by the teacher's rebellious spirit and 'the other side of Bomberg, apart from the theorising and proselytising — his extra sensitivity to the figure and to proportion: There are those who claim that Auerbach has merely developed Bomberg's technique. Anyone who has eyes can see the lie. He had very firm views when he encountered Bomberg at the Hampstead Borough Polytechnic. Catherine Lampert, one of Auerbach's devoted sitters, takes up the story with him in her 1978 interviews. 'The thing that I knew was that one's teachers were going to be silly fools and that one was going to rebel against them. Then, I was 17 and I went to Bomberg's class where he said to me, "Oh so you think I'm a silly old idiot don't you?", or something like that, and I said in my 17-year-old arrogance, "Yes I do." He was delighted. . .

Auerbach's artistic preferences are sometimes surprising. He admires a wide range of French 19th-century artists. 'In- gres', he notes, 'has an intensity as though some nut had been turned tighter, tighter and tighter till it seems to burst, which I find even more stimulating than Delacroix, although Delacroix would have been much closer to my way of painting. There are curious disparities in these things, because Delacroix, whose paint looks so impassion- ed is a marvellously sensible craftsman.' He often visits the National Gallery when he is having trouble with a painting. He doesn't look at similar images, just searches for quality, grandeur and definition to wash his vision. He wants 'to compare the sensation one gets from something very good' to what he has just been doing.

It is impossible to assess any great artist's work simply in terms of artistic references. Auerbach leads a highly ascetic life, but it is one that has been shaped by modern events. He came to England when he was seven and never saw his parents again. He went to an austere, intellectually snobbish, isolated boarding school, which harboured the idea that artistic activity was worth- while. He had a brilliant, conscientious- objector drama teacher. Young Auerbach played Everyman, was Fabian in Twelfth Night, but never entered the stage on that occasion because the rehearsals were so exacting that they didn't get past Act I.

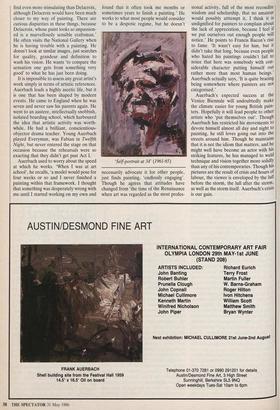

Auerbach used to worry about the speed at which he works. 'When I was at art school', he recalls, 'a model would pose for four weeks or so and I never finished a painting within that framework. I thought that something was desperately wrong with me until I started working on my own and found that it often took me months or sometimes years to finish a painting.' He works to what most people would consider to be a despotic regime, but he doesn't `Self-portrait at 34' (1961-65) necessarily advocate it for other people, just finds painting, 'endlessly engaging'. Though he agrees that attitudes have changed from 'the time of the Renaissance when art was regarded as the most profes- sional activity, full of the most recondite wisdom and scholarship, that no amateur would possibly atttempt it, I think it is undignified for painters to complain about the lack of appreciation, because I feel if we put ourselves out enough people will notice.' He points to Francis Bacon's rise to fame. 'It wasn't easy for him, but it didn't take that long, because even people who hated his paintings couldn't fail to noice that here was somebody with con- siderable character putting himself out rather more than most human beings.' Auerbach actually says, 'It is quite bracing being somewhere where painters are not categorised.'

Auerbach's expected success at the Venice Biennale will undoubtedly make the climate easier for young British pain- ters. Hopefully it will lead people to other artists who 'put themselves out'. Though Auerbach has restricted his movements to devote himself almost all day and night to painting, he still loves going out into the streets around him. Though he maintains that it is not the idiom that matters, and he might well have become an actor with his striking features, he has managed to weld technique and vision together more solidly than any of his contemporaries. Though his pictures are the result of crisis and hours of labour, the viewer is enveloped by the lull before the storm, the lull after the storm, as well as the storm itself. Auerbach's crisis is our gain.

Previous page

Previous page