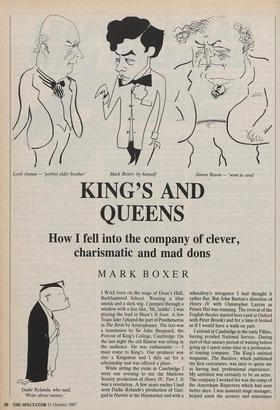

Lord Annan — 'perfect elder brother' Mark Boxer, by himself

Simon Raven — 'went to seed'

KING'S AND QUEENS

How I fell into the company of clever, charismatic and mad dons

MARK BOXER

Dadie Rylands, who said, 'Write about money.'

I WAS born on the stage of Dean's Hall, Berkhamsted School. Wearing a blue smock and a dark wig, I jumped through a window with a line like, 'Hi, laddie'. I was playing the lead in Shaw's St Joan. A few Years later I played the part of Peisthetaerus in The Birds by Aristophanes. The text was a translation by Sir John Sheppard, the Provost of King's College, Cambridge. On the last night the old flaneur was sitting in the audience. He was enthusiastic — I must come to King's. Our producer was also a Kingsman and I duly sat for a scholarship and was offered a place.

While sitting the exam in Cambridge I went one evening to see the Marlowe Society production of Henry IV, Part 2. It was a revelation. A few years earlier I had seen Dadie Rylands's production of Giel- gud in Hamlet at the Haymarket and with a schoolboy's arrogance I had thought it rather flat. But John Barton's direction of Henry IV with Christopher Layton as Prince Hal was stunning. The revival of the English theatre started here (and at Oxford with Peter Brook) and for a time it looked as if I would have a walk-on part.

I arrived at Cambridge in the early Fifties, having avoided National Service. During part of that uneasy period of waiting before going up I spent some time in a profession- al touring company. The King's satirical magazine, The Basilion, which published my first caricatures, was later to quote me as having had 'professional experience'. My ambition was certainly to be an actor. The company I worked for was the rump of the Amersham Repertory which had seen better days. I was assistant stage manager, helped paint the scenery and sometimes played the smallest part. For a country house thriller this meant translating a maid into a footman. The actors were kind to me, though I didn't fall in love with them as I had done previously with the musicians recruited by Anthony Hopkins to play his original score for The Birds. I had been transfixed by the wit of John Amis, the suavity of Neville Marriner and in particu- lar the lure of an upper-class cellist who capitivated me by wearing corduroys under her evening dress. Their memory came back to me many years later when I had to draw Moreland for the cover of one of Anthony Powell's paperbacks.

When I arrived at Cambridge my first steps were in the direction of the ADC. For over a year I played a number of smallish parts — this time round I played Bluebeard instead of St Joan. Usually I was directed by John Barton or Peter Wood, but slowly my ability seemed to drain away. The straight-forward 'feeling' which had served me well as a boy actor didn't work in more complex productions. I then made the mistake of taking a leading part in a weak production and learned the life-long rule that you should only work for real talent. I also began to meet many professional actors, sometimes through Dadie Rylands, who became my tutor. The Oliviers would come to his rooms for drinks when they were in a try-out at the Arts Theatre and I remember being slight- ly alarmed by a sinister companion of Dirk Bogarde's. There were also lesser theatric- al figures I met in the various drinking clubs off Shaftesbury Avenue which I frequented in the vacations. Did I really want to spend the rest of my life with these self-centred, camp monomaniacs?

If I was born on the school stage I came of age at King's. The col- lege had many peculiari- ties. Perhaps the most rewarding was the tradi- tion that the dons mixed with the undergraduates at lunch. In this way I Keynes and Kaldor, de- finitely among the clever got to know such diverse figures as Eric Hobsbawm,the engaging Marxist historian and the archaeologist, Charles McBurney who gave me some unexpected advice one evening at a party in Gibbs Building: 'My dear Mark, you are getting to the age when you are particularly attractive to women you must fuck and fuck and fuck.' Dadie Rylands gave me two rather diffe- rent pieces of advice. I had written a conscientious piece in Granta about Den- ton Welch and asked for his comments. `Draw, dear boy, draw,' he said. The other was that if I did write: 'Write about money rather than love.'

Every memoir of university life pays tribute to some affable, eccentric, bachelor don. Maurice Bowra is the pro- totype. But King's had a whole cast of original, charismatic, clever, famous and mad dons. Sheppard himself was a flam- Beves (left) — unlikely spy; Forster (above) — 'Edwardian tobacconist'; Sheppard 'overplayed character actor' boyant example. His hair was said to have gone instantly white when he was appointed Provost. He chugged around the college at a slow speed, beaming at all his `dear boys' with a stick and a winged collar as props. He was probably a rather sweet man, but at the time he came over as an overplayed character actor. Years later it emerged that he regularly slipped off to the casinos of France where he was an inveter- ate player of roulette and had to be rescued after losing his shirt.

The ghosts of Bloomsbury haunted the college. In Dadie Rylands's rooms Carring- ton's painted fireplace faced you during tutorials. There was a bad Duncan Grant commissioned for the King's hostel. The friends and disciples of Keynes taught us, listened to us and teased us. His widow

could be seen in King's Passage and E. M. Forster had rooms near 'the drain'. Forster reminded me of an Edwardian tobacconist. He was a natural and gener- ous listener with a high pitched giggle. He once told me that he disguised real people in his novels by changing their sex.

For much of his time at Cambridge Morgan Forster lived in the house of the senior tutor, Patrick Wilkinson and his wife. Patrick Wilkinson worked at Bletch- ley during the war and was a recruiter for British Intelligence. I later wondered if they ever discussed espionage. This was the time of Burgess and Maclean's defec- tion which coincided with Morgan Foster publishing his view that he would prefer to betray his country rather than his friend.

Patrick was the quintessential King's don. As well as being a recruiter for British Intelligence he fulfilled the role of univer- sity orator, which meant when some dis- tinguished old con was given an honorary degree Patrick would have to create a Latin word for 'sparking plug' or 'jet engine'. He was also responsible for many years for the brilliant obituaries which appeared in the King's College magazine. They are in many ways a unique and remarkable history of ordinary English lives in the 20th century. He could invest the obituary of a country solicitor with some of the spirit of Justice Shallow. Patrick probably 'fingered' Neal Ascher- son for MI5. Neal was invited to the equivalent of Le Carre's Sarratt shortly after going down. Apparently one of the heads of counter-intelligence put his hand on Neal's knee. Surprisingly King's hadn't prepared him for this and he left in a huff.

A few days later I met Neal in the King's Road, Chelsea, and quite by chance asked him if he was going to be a spy. For over 20 years he assumed I was part of the circus.

Of all the Cambridge figures to be accused of being a Soviet agent, the Vice-Provost of King's, Donald Beves, was the most unlikely candidate. He appeared to be the mildest of men mainly interested in his Bentley, his collection of glass and acting. When he was safely dead the Times came out with the assertion that he was the Fifth man. I believe this was a typical cock-up in the highest echelons of the Times. The initial B was given to an extremely distinguished figure (still alive) by a confidant in a London club and Beves rather than Blunt came up on the Times radar screen. Later, when it was generally realised that Donald Beves was probably too laid-back for such a role, the hunt at Times newspapers switched to another B with a King's connection. For a time the Sunday Times played with the idea that the B they were after was one of Keynes's successors as bursar, Kenneth Berrill.

Many of the King's dons had worked in Intelligence or decoding at Bletchley dur- ing the war. My own particular favourite don was Noel Annan (ex-Intelligence). He was like the most perfect elder brother —

worldly-wise, forgiving and interested and amused by our views and gyrations. I have a great deal to thank him for. He credits me with being responsible for the King's tradition switching from being homosexual to becoming heterosexual. I switched myself but think the claim is far-fetched. Everyone's memory but mine seems inac- curate. For years Noel Annan's friend, Lord Rothschild (ex-MI5), thought I was the undergraduate who provided him with spermatozoa in a claret bottle for one of his experiments; in fact the donor was Simon Raven.

Eric Hobsbawm — 'engaging', When I first arrived at King's the most interesting undergraduate set revolved round Simon Raven. Clever and assured he appeared to be bigger and more bucolic than his contemporaries. He had already embraced a life view that seemed to me to be unusual for an intellectual: enjoyment. He had little time for new German words like 'angst' which had probably crept into the language through the pre-war pansy intelligentsia's love affair with Berlin. Simon had been strongly influenced by reading further in the classics than his masters at Charterhouse might have wished. He brought the spirit of Ovid and Catullus to lazy afternoons drinking Dolo- more's wines on the Backs. Later Simon went to seed. He couldn't get his disserta- tion together and started borrowing clothes from his friends, sleeping in guest rooms rather than stagger home to his lodgings and largely dispensed with socks. His memory must also have gone, as his book about his Cambridge days is largely inven- tion.

AI had fallen out of love with the theatre I had become more interested in people. A party seemed to me to have considerable merits above those of ex- periencing life at second hand through a play or book. It was some years before I came across the line in Zvevo's Confes- sions of Zeno which states roughly that

`life is neither unfair nor cruel, it is original'. Although I continued to be something of a performer I became essen- tially an observer for my last two years. Initially the choice had appeared to be between young 'wholesome' men in King's who rowed and belonged to the Christian Union and the 'fast' King's set led by Simon Raven. Outside the college the choice was between the hearties in the left hand bar of the Bath and the right hand bar which was full of Miles Malpractices yearn- ing to be Sebastian Flyte. The choice wasn't difficult; I would learn little from the former.

Slowly I realised the choice was much wider. I came to know non-conformist daughters in Newnham who were ravers, Arabs in Jesus, and a member of the Pitt Club who was such a dandy he sent his shirts to Switzer- land to be laundered. Apart from the poets like Thom Gunn and politicians like Hugh Thomas there were visiting dons from other cultures. In particular I remember Karl Winter who ran the Fitzwilliam and Marius Bewley who would ask 'Is he of the, er, Athenian persuasion?' One par- ticular discovery, the eccentric Catholic, Anthony de Houghton, was a flavour of the month during my last summer. I asked him to edit Granta while I revised for my finals. Nothing emerged on the copy date; promises of getting the likes of Genet to write proved groundless. All he produced was a blasphemous poem which led to the banning of Granta and my rustication. The college defended me as best they could. Forster criticised the proctors; Sheppard wrote to the Times to correct a statement suggesting the college rather than the University was responsible for sending me down.

For years King's College had a particular reputation: the dons were thought to be gay to the last man. Certainly there were many homosexual dons and the culture of the college was largely homosexual. But I never came across any example of dons 'proselytising' as the Times recently de- scribed Robert Helpmann in his obituary. (I was amused by a friend telling me that as a teenager he traipsed around in a dressing gown because he fancied Helpmann when he stayed with his parents, but without success.) I think I learnt everything from King's a certain 'attack' in conversation and be- haviour, the ability to look at issues from an unexpected angle, a suspicion of all generally held views, an affection for my fellow men, curiosity, the wish to be fair, the competing values of seriousness and pleasure. I had to go down to learn about double dealing and double standards, the third rate and the particular English vice, hypocrisy. But I had a grounding at King's in how life could be.

Mark Boxer is editorial director of Conde Nast.

Previous page

Previous page