`SO COOL, SO CALM, SO PERFECT'

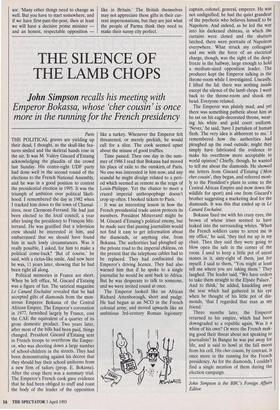

Anne Applebaum reports on the

Italians' increasing admiration for all things British

Parma HOWEVER YOU measure it, the good citizens of Parma enjoy one of the world's highest standards of living. The sun shines on them in the summer, the frost afflicts them only occasionally in the winter. The fame of the local food has worked its way into the language (Parma ham, Parmesan cheese) and the success of the local food- processing plants keeps a good number of Parmigiani in well-paid jobs. The Farnese palace remains intact, the churches are in good shape, the gardens are green and there isn't too much traffic. But when you ask Patrizia, a native of Parma, where she would live if she had the choice, she is truly torn. She sighs, 'If I could only spend six months every year in England, that would be perfect.' Patrizia helps to run the Anglo-Italian Club in Parma, managing a library filled with well-thumbed English books, an English-language school and a lecture series: real English writers sometimes come to visit Parma, along with the former London correspondents of Italian newspa- pers. Occasionally, the club meets socially, and the members talk about why they admire Britain — or England, rather, which is what the Italians usually call it. `The English have discipline, and we need some discipline around here,' one club member told me. 'The English are so cool, so calm, they behave so . . perfect.'

Britain, the perfect country: an unfamil- iar notion to the British, but an accepted fact among the Italian upper-middle class- es. It is nothing new, of course. The Ital- ians' fascination with their cool, calm dis- tant neighbours has been growing ever since British poets and time-wasters first began pushing up prices around the Piazza di Spagna, back in the days of the Grand Tour. Then, admiration was tempered with resentment: the British were rich, and they stole things. Many a decapitated marble torso in many an Italian park owes its headlessness to the British souvenir- hunters of an earlier era, and some of the resentment spilled over into our century. `Soon it is we who will be visiting your gal- leries, and it is you who will be serving us coffee,' is what an apocryphal Italian waiter told an apocryphal British traveller at the start of the second world war.

Nowadays, admiration need not be tem- pered by anything at all. British tourists still descend on Chiantishire every summer, but Portobello Road fills up with Italians every Saturday. The British may still be buying marble body parts from Italy, but no Italian home is now complete without silver toast- racks and leather-bound books, fake-log fires and hunting prints, all souvenirs from that August spent in London. And, actual- ly, one doesn't even have to go to London to get them any more. The best men's store in Naples is called Old England, while names like Londonderry and Thames Tweed can be found on labels up and down the Via Spiga in Milan. Even Ferragamo sells tweed jackets, Barbour jackets and leather shoes all'inglese — except that the tweed jackets are really cashmere, the Bar- bour jackets come in exciting shades of blue, and the shoes are made of soft, beau- tiful, milk chocolate-coloured leather, and fall apart in the rain.

Once nothing more than a male fashion statement, interest in things British is expanding. Inglesi, an Italian book about the quirky ways of the British (it explained, among other things, why the British don't wash, and why British girls don't wear stockings in the winter), recently sold tens of thousands of copies; in the Italian press, the foibles of Diana and Fergie are report- ed more carefully, and with more heart- felt emotion, than the troubles of Boris Yeltsin. Partly, this love of the British comes from dislike of the French (`too snob' they usually sniff) and the Italians have looked askance at Germany ever since Herr Hitler led II Duce so badly astray. The Spanish and Greeks are too close to be fascinating, the Swedes and Finns too distant; the Americans are vaguely resented for messing around in Italian politics after the war. The British, on the other hand, are neither too near nor too far, neither too strange nor too familiar. Besides, they possess a few quali- ties which the Italians feel they lack.

`I remember my first trip to London,' reminisced Emilio, a tweed-encased Milanese financier with wire-rimmed glass- es. We were sitting in a restaurant, listen- ing to the sound of oysters being slurped and `gintonics' being sipped. `The parks were so clean, no one threw rubbish in them. The tube was neat, there were no graffiti on the walls. The gardens were well-kept and the buildings well-painted, and I wondered, why can't we be like that too?' True, Emilio hadn't been to London for quite some time. 'But I am sure that the English will never change.'

In fact, to be an Italian Anglophile one doesn't necessarily need to know much about Britain, or even to like going there. Instead, Italian Anglophilia is all to do with admiring a certain idea of Britishness; it is all to do with wanting to be cleaner and more efficient, wanting better public services and trains which run on time; it is all to do with wanting to be `more Euro- pean', a phrase which means exactly the opposite in Italy from what it means in Britain. Europeans, according to the British, are slightly suspect, possibly cor- rupt and certainly foreign. `Europeans', according to the Italians, are uncorrupt and apolitical, hard-working and honest. And by this definition the British are the greatest Europeans of all. It is hardly a surprise, then, that Italian Anglophilia has blossomed along with the Italian bribery scandals. At the Savoy Club in Naples, I sat in a room filled with wick- er furniture and ceiling fans, while a group of earnest electoral reformers explained their programme. Like many Italians, they blamed their country's woes on proportion- al representation, a system which has kept the same gaggle of politicians in power for the past few decades. Power corrupts and all that; the knowledge that they would never be voted out is one reason why so many Italian politicians were unafraid to steal. Clearly, the laws have to change. `What we really want,' one university pro- fessor explained firmly, `is the Westminster system.'

It is a popular phrase — `the Westmin- ster system' — although not everyone here understands how it differs from what the French or the Americans have. That hardly matters: a Westminster system, many rea- son, will be better than the Italian system, because a Westminster system will be filled with unbribable civil servants — men in bowler hats, perhaps, who carry umbrellas and are always on time. That, at any rate, will be the image lingering in the minds of many Italians when they go to vote in next month's referendum on changing the elec- toral system. Because of Italy's desire for the Westminster system and all that a Westminster system entails, that referen- dum looks likely to pass — perhaps with spectacular majorities.

But will a new electoral system be enough to improve the government of Italy? `Of course not,' explained the profes- sor. 'Many other things need to change as well. But you have to start somewhere, and if we have first-past-the-post, then at least we will have a decisive prime minister and an honest, respectable opposition — like in Britain.' The British themselves may not appreciate these gifts in their cur- rent impersonations, but they are just what the people of Parma think they need to make their sunny city perfect.

Previous page

Previous page