" ACADEMIC QUESTIONS."

THE House of Commons having now, in a manner so satisfactory to the country, got through the public business of the session, and made wise provision for all our political wants betwixt this and next spring, begins to he well nigh at a loss for materials to exer- cise its collective wisdom upon. In this delightful state of leisure, (industry's best reward,) it found time on Tuesday night for a very long conversazione on the fine arts, in which was spoken an uncom- mon quantity of public-spirited things,—aspirations after the public weal in connexion with Corregios, Vandykes, &c. ; philanthropic prayers for the progress of portrait-painting, &c. And, for ex- ample, that sanguine friend of the people, Sir ROBERT PEEL, thus chivalrously and cheaply declaimed- ,. He hoped to live to sec, in the most favoured part of Hyde Park, a magni- ficent structure devoted to the reception of works of art, not merely for the accommodation of the Sovereign, but for the accommodation and delight of the people of this country ; for their amusement, their intellectual refinement, and their improvement in the arts."

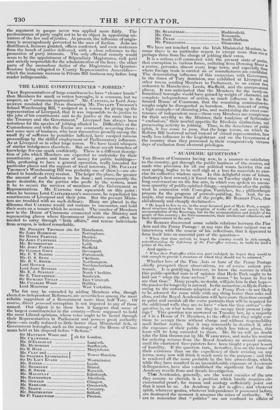

Sir ROBERT discovered some subtile relations between the Fine Arts and the Penny Postage : at any rate the hatter subject was so interwoven with the course of his reflections, that it appeared to form itself into an essential part of the question- " When that time arrived, he hoped the country would be rich enough, notwithstanding the deficiency of the Post-office revenue, to build for itself a palace of the arts."

And again-

4, When their Post-office whim was part indulged, be hoped they would be rich enough to provide a structure of which they should not be ashamed."

Whether love of the Fine Arts or hate of the Penny Postage chiefly prompted these observations, we of course cannot pro- nounce. it is gratifying, however, to know the manner in which this public-spirited man is of opinion that Hyde Park ought to be laid out " when the time arrives." It seems " he hopes to live to sec that time." Many people, no doubt, will join hint in that hope— the passion for longevity is natural. In the mean time, as Hyde Park— owing to the unfortunate adoption of a Penny Post—is not likely to be adorned for some while with any thing better than oaks and elms, and the Royal Academicians will have more than time enough to paint and varnish all the extra portraits that will be required for the additional walls they are to have " when the time arrives"—the question is, on what terms are they to occupy their present lodg- ings ? This question was answered on Tuesday last, by a majority of 5 in a House of 71 Members, to the effect that they might con- tinue to occupy them without charge and without responsibility until further notice. But it may reasonably be doubted if after the exposure of their public doings which has taken place, this lease will be long extended to them. Mr. 111-nn will no doubt take the hint thrown out by Mr. WA Biluros, and make his motion for ordering returns from the Royal Academy im annual motion, until the chartered face-painters have been taught a proper lesson of humility. If the question turn, hereafter, less on the terms of their existence than on the expediency of their existing on any terms, many now will think it much more to the purpose ; and this is rendered all the more probable by the late proceedings, which, while they have resulted in no inconsiderable exposure of Academic delinquencies, have also established the significant fact that the Academy recoils front and dreads investigation. That Academies, generally, are the worst enemies of the arts they assume to cherish, is a position which hardly requires cir- cumstantial proof; for reason and analogy sufficiently point out that it must be so. An Academy is Art in office ; and whatever spirit, whatever genius, whatever independence it possessed before, are destroyed the moment it assumes the robes of authority. We are to remember that "politics" are not confined to affairs of

state, or to those bodies that take part in them, but that they arc infused through all the ramifications of public life. No society of

m be chartered for any purposes of art, science, trade, or men eerenterprise, but immediately there springs front their incor- poration a sort of politics, an esprit de corps, of which it may be

but safe enough to say that, in difficult to attempt a full analysis, its nature, it is opposed to the public good, and can seldom be left with impunity unrestrained and unregulated. It suggests no ar-

gument against the formation and encouragement of public coin- panics, but it describes the respect in which they are most ob-

noxious to popular jealousy, and in which the control of a superior authority is most needed to render their institution really beneficial. With respect to Academical Societies, there is every reason why we should believe that even the wisest and most provident regula- tions of government can never convert them—we will not say into beneficial, but into inoffensive institutions ; and this for reasons already suggested from the analogy of politics. In politics, what is the neutralizer of all talent ?—Office. What is the annihilator of all enterprise ?—Office. What is the grave of all honesty ?—Office. What is the great subduer of genius and truth, and leveller of pub- lic virtue?—Office. What is the cold formalizer of manners; the heartless reducer of all things genuine and characteristic to one insipid, lying uniformity ?-6ffice. What a secret have we here

then for stripping the fine arts of every shred of their peculiar grace and honour! What a plan for purging them of every particle of their gold, and leaving the retbse—for public admiration too ! "Put them into office "—this was the malicious counsel which might have been for answer to the question, " How shall we soon- est extinguish the fine arts in this country ?"

We consider our analogy strictly accurate. It has usually been the case that an art has numbered votaries of extraordinary merit

and high celebrity up to the Unto and even at the time of its making

the fatal move which places it, as it thinks, on a higher, but really on a lower level—on a level with commercial bodies, joint-stock

companies, &c. (of which, indeed, it actually becomes one); but after that Use move, such art, instead of rising higher, has inva- riably begun to sink into contempt.* For the glory of an art is not in the number but in the quality of its achievements; and if it be granted (which it may) that .academics enlarge the commercial operations of the art—that is, raise up a great body of artists of mechanical ability, and thereby increase the market for produc- tions,—this circumstance makes out a strong claim for Academies to the gratitude of the Board of Trade ; that is all. In fact, the distinction which Sir ROBERT PEEL was at pains to make the other night was quite too fine— "There was a clear distinction between all commercial societies—those con- teeehyl with the acquisition of pain, and institutions and intended tier the pro-

motion of public objects. if a society were intended strictly for the promo- tion of public objects, he should be sorry to deny the right of the House of Commons to inquire into such societies; and lie felt bound to say, that he

thought the fact of the Royal Academy being accommodated with apartments at the public charge added to the right which that House possessed to call for the returns required."

Time Royal Academy, by this rule, might easily resist investiga- tion if it chose ; for it certainly is a " commercial society," if' it sad only the candour to say so. Now it may or it may not be considered a merit in Academies to enlarge the number of respect- able mediocre artists—to increase the middle classes while inkling BO " new creations" to the ellitoCl'ileg of art: but this, in any ease, remains their damning reproach, that, dealing solely in things second-rate, they yet challenge, and untbrt(mateG by their artificial position obtain, first-rate honours. Proclaim them trading com- panies ; strip them of their power to be thought nurseries of na- tional genius; take away the high sanction that misleads the public into a deference to pretensions which are simply ridiculous ; and then, if they will, let them continue to discharge their present functions—it will not be at the expense of truth and justice : me- diocrity may still flourish and increase, but genius will no longer be starved to feed it.

Speaking of Arts and Academies, we do not know how it. is that in this country " the Fine Arts" should imply painting and sculp- ture only, but 110t music ; and, by a correspentling slight, that " The Royal Academy" should emphatically point out the esta- blishment in Trafalgar Square, and by no means that in Tcnterden Street. Yet music is an art—if report speak true, even a "fine art ;" and it too boasts its Royal ALmlenty. Is any Member of the House of Commons aware of these remarkable facts ? and may we ask, is an attempt to be made to deliver the arts of design from the thraldom of Academic government, and will no finger stir to relieve music from a worse moral degradation ?

But of this enough for the present. Royal Academies must look to themselves : there is sontethng rotten in their state, if not in their very natures, and investigation will not stop because they are pleased to deprecate it.

* Exchanging celebrity in painting, for example, for celebrity in //Wog. The Royal Academy, with its "peuB'o•orthi of bread to all this sack "—its 4,5811/. " in sending young men to Italy" to its 19,750/. in carouAn,—nittst take care lest it give rise to some nicked parody on that dialogue of LrclAN'S in which, amongst various causes argued Mine Jupiter in the Areiipa,t14, we find the sinouldr and suggest ive etise" Drharreiterg owes Vic " We don't know, by the way, how finr a comparison might be instituted between the " Royal Academy" and the "`-etas Academia;" but one difference immediately occurs to us. It was a law in the latter, that no one frequenting it should rough. It would be impossible to enfiiree this rule in the " Royal Academies" of our time, unless yisitYrs were strictly excluded; their perfoi:in- ances being compared with their pretensions-11EnActxrus himself must

Previous page

Previous page