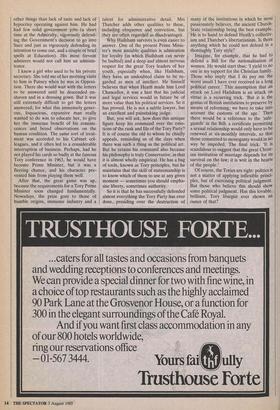

ANTIQUE TORY ADVOCATE

Survivors: A profile of Lord Hailsham, venerated ornament

BOTH of the questions generally asked about Quintin Hailsham, (over whose pay increase the Government was nearly defe- ated in the Commons last week and, on an amendment, was indeed defeated in his own House) — Why has he never become Prime Minister? Why, at the age of 78, he is still a venerated ornament of the Tory Party and an apparently indispensable member of Mrs Thatcher's Government? — are in fact very easy to answer.

True, during the first half of his political career, he seemed to have many of the qualifications then deemed necessary to a Tory prime minister. The son of a former Lord Chancellor, he came from the right kind of stable, belonging to what used to be distastefully described as 'the magic circle'. He was a brilliant classical scholar and an outstandingly able barrister; he had entered politics at a famous by-election after the Munich agreement, when Cham- berlain's Government was being be- laboured by high-minded left-wing intellec- tuals, including Lindsay, the Master of Balliol, whom Hailsham (then Hogg) suc- cessfully defeated. There followed a good war record, ,a return to wartime politics and the statutory period of rebellion against the party whips then thought to be an almost essential prelude to high office: 'The boy's a hothead, of course, but one must admire his spirit.'

At this time, he was largely running the Tory Reform Group, a movement devoted to the recurring task of reviving the Disrae- lian tradition, an occupation designed by the Tory establishment to provide a re- latively innocent outlet for the generous instincts of promising politicians still at the stage of political adolescence. He duly got a junior ministry in Churchill's brief post- war Tory Government.

A splendid parliamentary and platform speaker, only one obstacle seemed to stand between him and eventual tenancy at Number Ten — the family curse, an hereditary peerage. Even that impediment had been removed by 1963 as a result of a new law designed to enable ambitious politicians to renounce such peerages. At the famous Tory Party conference of that year, Macmillan, having fallen ill, announced, by a message read from the platform, his imminent resignation. He was known to favour Hailsham, now in the Lords, as his successor. Hailsham was the darling of the grass roots, having revived the party's fortunes by his rumbustious activities as Party Chairman in the mid- Fifties. He promptly announced to the conference his intention to give up his peerage in order to place himself at his country's disposal. His audience had an immediate orgasm.

But, of course, he had made a fun- damental mistake. The choice of Tory leaders is not made by party conferences; what mattered was backbench Commons approval; and the way to get that, at least in those days, was to hang back diffidently in order to become the compromise candi- date. Home performed this self-abnegating act to perfection; Butler looked ambitious but unexciting; Hailsham looked frenzied and immensely ambitious.

In the eyes of backbenchers, there were other things than lack of taste and lack of hypocrisy operating against him. He had had few solid government jobs (a short time at the Admiralty, vigorously defend- ing the Government's decision to go into Suez and just as vigorously defending its intention to come out, and a couple of brief spells at Education). His most fervent admirers would not call him an adminis- trator.

I knew a girl who used to be his private secretary. She told me of her morning visits to him in Putney when he was in Opposi- tion. There she would wait with the letters to be answered until he descended un- shaven and in a dressing gown. But it was still extremely difficult to get the letters answered; for what this immensely gener- ous, loquacious, expansive man really wanted to do was to educate her, to give her the immense benefit of his reminis- cences and broad observations on the human condition. The same sort of treat- ment was accorded to his Cabinet col- leagues, and it often led to a considerable interruption of business. Perhaps, had he not played his cards so badly at the famous Tory conference in 1963, he would have become Prime Minister, but it was a fleeting chance, and his character pre- vented him from playing them well.

After that, the great game was up, because the requirements for a Tory Prime Minister soon changed fundamentally. Nowadays, the prize goes to those of humble origins, immense industry and a talent for administrative detail. Mrs Thatcher adds other qualities to these, including eloquence and conviction, but they are often regarded as disadvantages.

Why Hailsham survives is, even easier to answer. One of the present Prime Minis- ter's most amiable qualities is admiration for loyalty (in which Hailsham can never be faulted) and a deep and almost nervous• respect for the great Tory leaders of her youth, especially when, like Hailsham, they have an undoubted claim to be re- garded as men of intellect. He himself believes that when Heath made him Lord Chancellor, it was a hint that his judicial and legal services would in future be of more value than his political services. So it has proved. He is not a subtle lawyer, but an excellent and painstaking judge.

But, you will ask, how does this antique figure keep his command over the emo- tions of the rank and file of the Tory Party? It is of course the old to whom he chiefly appeals, reminding us of the days when there was such a thing as the political art. But he retains his command also because his philosophy is truly Conservative, in that it is almost wholly empirical. He has a bag of tools, known as Tory principles, but he maintains that the skill of statesmanship is to know which of them to use at any given moment — sometimes you should empha- sise liberty, sometimes authority.

So it is that he has successfully defended almost everything the Tory Party has ever done, presiding over the destruction of many of the institutions in which he most passionately believes, the ancient Church- State relationship being the best example. He is to hand to defend Heath's collectiv- ism and Thatcher's libertarianism. Is there anything which he could not defend in a thoroughly Tory style?

Imagine, for example, that he had to defend a Bill for the nationalisation of women. He would start thus: 'I yield to no one in my support for the Christian family. Those who imply that I do pay me the worst insult I have ever received in a long political career.' This assumption that an attack on Lord Hailsham is an attack on virtue is a recurring trick. 'But it is the genius of British institutions to preserve by means of reforming; we have to take into account the customs of the age.' Then there would be a reference to the 'safe- guards' in the Bill: a certificate permitting a sexual relationship would only have to be renewed at six-monthly intervals, so that those committed to monogamy would in no way be impeded. The final trick: 'It is scandalous to suggest that the great Christ- ian institution of marriage depends for its survival on the law; it is writ in the hearts of the people.'

Of course, the Tories are right: politics is not a matter of applying inflexible princi- ples, but of exercising political judgment. But those who believe this should show some political judgment. Has this lovable, brilliant, Tory liturgist ever shown an Ounce of that?

Previous page

Previous page