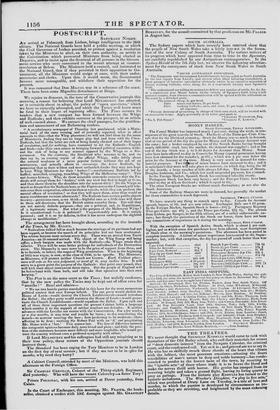

THE THEATRES.

WE never thought that SHERIDAN KNOWLES would come to rank with dramatists of the Old Bailey school, who cull their materials for scenes of "deep domestic interest" from the Newgate Calendar, the criminal court, and the condemned cell. Yet so it is ; and grieved are we to say it. He who has so skilfully struck those chords of the heart that vibrate with the loftiest, the most generous emotions—attuning the finest sensibilities of man's nature to deep and noble harmony—has conde- scended to pander to the lowest taste of the town, by resorting to the "ignoble arts" of those whose trade it is to freeze the blood and make the nerves thrill with horror. His genius has stooped from its towering height and taken a ground flight, leaving its living quarry to prey on garbage. From the historic play Knowtrs has turned to the hysteric melodrama. The Wrecker's Daughter, "a play in five acts," which was produced at Drury Lane on Tuesday, is a tale of love and murder, in which the passion is developed by circumstances as im- probable as they are revolting, and heightened by the most sickening details.

Marian, " the Wrecker's Daughter," is the object of the lust rather than love. of Black Norris, the most desperate of the wreckers on the coast of Cornwall,—a villain who, by way of keeping himself in coun- tenance, affects to believe every one else as bad, though "circumstance makes a difference ;" and who " hates the show of good in man and woman, but in woman most." Of course he does not make love like other men—"e'en for fair ends be cannot take fair means :" besides, Marian is betrothed to Edward, a young sailor, who at the opening of the play leaves her to take his last trip to sea—the one that is to fur- nish them with the means of marriage. Moreover, Marian has a horror of Black Norris : " his father is a convict, serving in a distant land, for crime done on the wreck-strown shore," and he himself is suspected of stopping the breath of the bodies he plunders. Norris's peculiar mode of obtaining Marian's consent to marry him, is the cause of all the misery; and his plan being somewhat intricate in its working, requires some minuteness of explanation. The ruffian's first object is to get old Robert, Marian's father, "to take a sail, and leave the girl alone :" and thus he sets about it. A ship is driven ashore ; and Robert, despite of his promise and his daughter's entreaties, joins the wreckers on the beach. Black Norris cajoles him ; and, under the pretence of helping him to plunder, directs him to a body that is washed ashore. Marian, who has followed her father, and frightens him with ghostly recollections of her dead mother, persuades him to come home. While he is gone to fetch his " boat-hook and gear," Black Norris steals in, and in sight of the maiden, stabs the body,—expecting that she will mistake him for her father ; which she (very naturally !) does, and forthwith faints away. Robert reenters ; and seeing the body lie so tempting with pockets full of gold, thinks " it were folly to leave it in the pockets of the dead," and " for the last time" too : so he empties them. While he is rifling the corpse, other wreckers, sent by Black Norris, come in ; and finding Robert's knife sticking " fast in the dead man's breast," take their old comrade into custody. Black Norris, being one of the watch by night, finds an opportunity to tell Robert that he thinks him innocent—that some one has laid a trap for him—generously offers to let him escape, and gives him money to cross the sea; frightening him into compliance by a vivid picture of the horrors of the gallows. The old man, however, calls to bid his daughter good bye ; and, finding from her altered manner that she believes him guilty, scorns to escape, and suffers himself to be captured. He is examined in "the Justice-room," and committed for trial, on the evidence of his daughter ; who is so taken up with the notion of her heroic virtue in sacrificing a father's life to the sacred regard for truth—like another Jennie Deans—that she never for a moment doubts that she could be mistaken. The old man, too, is content to upbraid his daughter, with biting irony, bitterly for her gra- tuitous and unnatural cruelty in wantonly swearing away his life for no object whatever ; and does not so much as question her as to her reasons. Black Norris, exultingly anticipating the success of his plot, thinks he has only to confess the trick and the old man is free, and his motive will absolve him-

" They will but chide me, and, at worst, will say The scheme was daring—yet a lover's one."

Accordingly, first spreading a report of Edward's death by drown- ing—which every body is bound to credit—lie declares his love to Marian, and asks her to marry him, offering to prove her father inno- cent if she will. She, nothing wondering, consents; and Norris, by some "hard swearing," it is hinted—an alibi perhaps—gets the old man acquitted. On the morning of the wedding-day, Edward comes back ; but Marian, whose principles seem best sustained by the wretch- edness of herself and those most dear to her, turns from him, and in

answer to his appeals, only says that she loves him "better than ever," and implores him to forgive her; and then, with stoical fortitude, gives her hand to Black Norris before her lover's face, and goes out leaving him to guess the truth and resolve the mystery how he may. How- ever, he is soon satisfied ; for he meets the bridal procession at the church-door, calls Marian "an angel," and says "no tongue can speak the beauty of so fair a deed :" and the couple would have been married—notwithstanding the remonstrances of the parson, who does not like Black Norris's looks, and thinks the bride a little crazy, (which we feared from the beginning of the play)—but as they are en- tering the church, a madman comes forth, who proves to be an acces- sory after the fact in Norris's crime, who had returned just in the very nick to ease his conscience by confession, and to convict Black Norris of having stabbed the drowned man while yet his body was warm—and that man Norris's own father! Lest there should be any doubt, however, Norris stabs his accuser, and so proves himself a mur- derer to the satisfaction of all parties ; and the curtain drops while the parson is blessing the true lovers.

What moral purpose is intended by this disgusting concatenation of horrors ? If it be to show the triumph of principle in adhering to truth under all circumstances, why make the seeming truth, upheld by such frightful sacrifice, an actual lie ? If to point a moral on the heart- less trade of the wrecker, more simple means had been better ; for even the revolting features of the wrecker are lost sight of in the

fiendlike malignity of the villain Norris. The alteration of the title in the printed copy to The Daughter, seems to imply that the main purpose of the drama is to exhibit the severest trial of filial affection : if so, we can only regret the means employed, and that one of the holiest affections of human nature should be developed by the foulest circumstances. But the truth we take to be, that the author had no direct moral purpose in view. The subject seems to have sickened him from the first—as he hints in a brief preface ; and he was only in- duced to carry it through, by the recommendation of a friend " in whose taste," he says " I bad great reliance "—we should be disposed to question both his taste and judgment. That there is great power

in several scenes, and that the situations are wrought up to intensity, the painful interest that the play excited—not to speak of the ap- plause bestowed on it — are sufficient proofs. The scene where Robert discovers *hat his daughter believes him guilty, awl that where he upbraids her for her testimony against him, are touching in the extreme. The parting of the lovers—the scene where Robert notes the approaching storm, and that where be bursts from his daughter to go to the shore—the interview between Norris and Robert on the beach—are all admirable : but the purposeless soliloquy of Marian in the storm—her appeal to the pity of the tendir.hearted turnkey in

top-boots—and the last scene with the clergyman-_are overwrought to a ludicrous extent.

Throughout the play, there are evidences of carelessness and haste; iteration of ideas, and straining of similes. All the characters dream dream, and talk of going mad : nautical phraseology is em- ployed to a pedantic excess, and mean vulgarisms are made use of in some cases where the speaker in the next breath is on the stilts of style. The fitness of blank verse at all, indeed, bit the dialogue of a story of low life, where tha scene is laid in our country and at the present day, may be doubted : as it is, the rhythm is so broken up, that it often loses its effect in the delivery, and sounds too much like the prose run mad in which melodramas are commonly written. There is less of poetry, too, than we are accustomed to find in KNOWLES'S plays; though there are scattered about many of those homely and vigorous touches, and those more delicate strokes of sentiment, which give the glow of the heart to his writing. Such, for instance, us this.

"It follows not. !recluse The hair is rough, the dog's a savage one." •

" Sleek looks may be cotnprnions of rough heart ! I have found it many a time, --"

• • EDWARD.

" Marian'

Why driest thou hang thy head?" MARIAN. "My father is A wrecker."

EDWARD. • " SD was mine, Marian.

What then? We're not the children of their trade."

How beautifully is this familiar moral truth resaid! Marian is urg- ing her father to refrain from plundering-

RORFRT. " This night's the last."

MARIAN. " This night ! 0, no! The last night be the last ! Who makes his mind up to a thing that's wrong, Yet says he'll do that thing for the last time, bath hut commence anew a course of sift, Of which that last sin is the leading one, Which many another, and a worse, will follow.

At once begin !" The daughter's justification of herself in bearing testimony against her father, and her sorrow after, are finely expressed—

MARIAN. "1 felt

As if the final .judgment-day were come,

And not a hiding-place my heart could find To screen a thought or wish ; but every one Stood naked 'fore the Judge, as now my face

Stands before you! All things did vanish, father,

That make the interest and substance up Of human life—which, from the mighty thing That once was all in all, was shrunk to nothing.

As by some high command my soul received, And could not but obey, it did cast off All earthly ties, which, with their causes, melted Away ! And I saw nothing but tire Eye

That seeth all, bent searchingly on mine;

And my lips aped as not of their owe will, But of a stronger ; Isar nothing then But that all-seeing Eye—bra now I see Nothing but my father !"

Such poetry is of too high a quality lobe wasted on such materials. We hope this will be the last as it is the first of SHERIDAN KNOWLES'S plays of this class. When next he writes be will choose a subject for himself.

We have left little space to speak of the acting; which was excellent throughout. Miss HUDDART personates the Daughter : it is a most trying part; she is on the rack of circumstance through the whole five acts, though, like other sufferers, she becomes at last insensible to the strokes of Fate. Miss H III:MART sustains her tortures admirably : her energy and pathos never forsake her : a little over-acting is excusable in melodrama. WARDE looks Black Norris completely, and gives fearful effect to the villany of the character : it was a finished picture of its kind, and could riot have been done better. KNowLes throws some genuine touches of feeling into the character of the Father ; but it is a part requiring more art than he can boast of as an actor. He was heavy and prosy at times ; got into the dectimatic sing-song ; and at last, when he has nothing to do but to wait the chances that befall, we wished Lim off the stage. COOPER makes a very creditable lover; and DIDDEAR, as Wolf, surprised the audience by his power in the scene where he gradually unfolds the story of the murder to Norris.

The piece was announced to be played three times a week till further notice. Whether its success will rival that of Jonathan Bradfbrd, re- mains to be seen. KNOWLLS may gain by it in pocket what he has lost in reputation.

Previous page

Previous page