Chess

By PHILIDOR

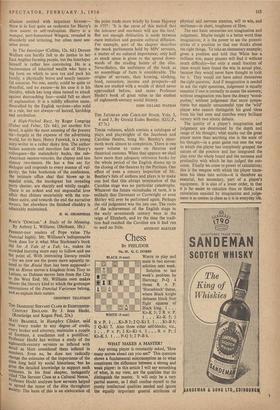

No. 35. G. C. DOBBS BLACK (6 men) WHITE to play and mate in two moves: A% solution next week.

Solution to last week's problem by Hartong: P-Q 4 threat R x P.

1 . . . Kt-K 5; 2 B x P. 1 ... Kt-B 3; 2 Q-Kt 3. 1 . . . Kt-B 5; 2 Q-Kt 7. Also three other self-blocks, viz., 1 . . P x P; 2 Kt-Kt 4. 1 . . R x P; 2 Kt-K 3. 1 . . . P-Q 3; 2 P-B 6.

WHAT MAKES A MASTER?

Any strong player is constantly asked, `How many moves ahead can you see?' This question shows a fundamental misconception as to what constitutes the difference between a strong and weak player: in this article I will say something of what, in my view, are the qualities that do distinguish the master. It will only be a very partial answer, as I shall confine myself to the purely intellectual qualities needed and ignore the equally important general attributes of physical and nervous stamina, will to win, and resilience—in short, toughness of fibre.

The two basic necessities are imagination and judgement. Maybe insight is a better word than imagination; it is the power to see the potenti- alities of a position so that one thinks about the right things. To take an elementary example; given a position and told that White has a brilliant win, many players will find it without much difficulty—but only a small fraction of them would have found the win in actual play, because they would never have thought to look for it. They would not have asked themselves the right question. And if imagination is needed to ask the right questions, judgement is equally essential if one is correctly to assess the answers; without imagination you have the dreary 'wood- pusher,' without judgement that more sympa- thetic but equally unsuccessful type the 'wild' player who cannot distinguish his good ideas from his bad ones and matches every brilliant victory with two idiotic defeats.

The quality of a player's imagination and judgement are determined by the depth and range of his thought; what marks out the great player more than anything else is the scale of his thought—in a great game one sees the way in which the player has completely grasped the nature of the position and has integrated the play over the whole board and the sureness and profundity with which he has judged the out- come. Finally we come to power of calculation; this is the weapon with which the player trans- lates his ideas into action—it is therefore an essential, but secondary, part of a player's equipment. It is also of a lower order, in that it is far easier to calculate than to think; and calculation unaided by imagination and judge- ment is as useless in chess as it is in everyday life.

Previous page

Previous page