WE'RE DOING BETTER THAN EUROPE

Tim Congdon shows how the reduction

of government spending is placing Britain in a virtuous circle of prosperity

ONE of the geopolitical clichés of the 1980s was that the countries of Europe had to 'harmonise' their economies if they were to 'progress' or 'advance' towards greater political integration. The assumptions be- hind this cliché were not only that political integration was a Good Thing (hence the unthinking use of words like 'progress' and 'advance), but that the various economies had to have essentially similar fiscal and monetary structures if they were to be truly unified. There was also a view, never far from the surface of debate, that countries pursuing distinctive policies might behave unfairly towards the rest. The phrase 'so- cial dumping', used to describe countries with low levels of social security provision and correspondingly high attractiveness to internationally mobile investment capital, reflected this concern.

How far did the cliché translate into action? Did the countries of Europe be- came economically and financially similar in the 1980s or less? And how far did Britain conform to the expected pattern? Did Britain become more like the 'typical European country' or not?

These questions are, of course, at the centre of the tensions within the Conserva- tive Party about Britain's attitude towards Europe. Mrs Thatcher has isolated Britain from other European countries by refusing to support the proposed Social Charter, with its recommendations of workers on boards, compulsory holiday months, mini- mum wages and the like. By so doing she has invited the charge that Britain might itself indulge in a little 'social dumping'. She has also made clear to Conservative members of the European Parliament that, whatever they might think about the mat- ter, she is less than enthusiastic about visions of an early European federal union. For the foreseeable future she clearly wants Britain to retain sovereignty over most social and economic issues, and so to have the option to remain different from the rest of Europe. There is one yardstick of national dif- ferentiation — the ratio of government spending to gross domestic product — which is not only vital in its own right, but

also reflects much else of importance, including tax levels and the broader social philosophy of government. It turns out that, on this measure, Britain has been diverging from the rest of Europe, not harmonising towards it. Indeed, Britain now has the lowest ratio of government spending to GDP in the European Com- munity. If recent trends continue, by the mid-1990s the divergence between it and the rest of Europe will be conspicuous.

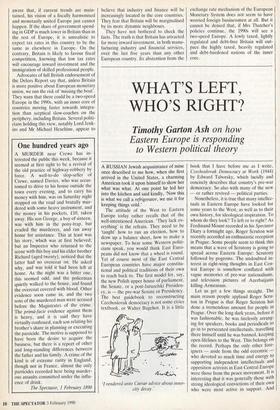

The key numbers are set out in the accompanying table. In 1980 the four large European countries — West Germany, France, Britain and Italy — were quite close in their ratio of government spending to GDP, all lying between 42 per cent and 48 per cent. This similarity of government shares had prevailed for about 20 years. There had been a tendency for the govern- ment share in GDP to rise steadily over time in all four countries, but only margin- al changes in relative positions. As far as the smaller countries were concerned, the main feature was a marked contrast be- tween the large welfare states of north

European countries like Denmark and the Netherlands, and low levels of government spending in the Mediterranean countries such as Spain, Portugal and Greece.

In the early 1980s the rankings began to change. The tight control over public spending in Britain, due to the Thatcher Governments' policies, had the effect of reducing the state share in GDP from almost 48 per cent in 1981 to a little over 43 per cent in 1987. During the Lawson boom this trend was reinforced by the buoyancy of the economy, which reduced spending on unemployment benefits and other forms of social security, and also caused GDP as a whole to grow faster than spending on education, health and other categories little affected by the business cycle. By 1989 government spending was less than 40 per cent of GDP.

Meanwhile other European countries followed their own paths. West Germany went in the same direction as Britain, but it did not go so far. The share of government spending in GDP fell in the 1980s, but only from about 48 per cent in 1980 to 45 per cent last year. By contrast, France and Italy experienced significant rises in the public-spending share. In France this rise was concentrated in the early years of the Mitterrand government, but has not been reversed by the more pragmatic policies subsequently. In Italy the growth of state expediture has not yet been properlY checked and there is a particular problem because of the unsustainable increase in the ratio of public debt (and debt interest) to GDP.

The behaviour of government spending in other European countries was, if any- thing, even more remarkable. The north European countries which had had high ratios of public spending to GDP in 1980 continued to have high ratios of public spending to GDP in the late 1980s, with little change in the ratios or relative posi- tions. But the Mediterranean countries embarked on a decade of unprecedented fiscal expansionism, with the shares of government spending in GDP rising from about 30 per cent in 1980 to almost 45 per cent today. The rapid growth of public Government outlays as a proportion of gross domestic product in the European Community (per cent)

1968 1973 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 UK 39.1 40.4 42.7 44.9 47.7 47.1 46.9 47.5 46.2 45.5 43.2 39.0 38.8 Portugal 20.9 21.3 36.2 25.9 43.9 43.0 47.9 44.4 43.4 43.9 42.8 42.6 41.8 Spain 21.3 23.0 30.5 32.9 55.6 37.5 38.8 39.3 42.1 41.7 43.0 43,0 43.2 Ireland 32.5 39.0 46.8 50.8 52.5 55.3 55.3 53.3 54.5 54.7 49.8 47.1 43.8 W Germany 39.1 41.5 47.6 48.3 49.2 49.4 48.3 48.0 47.5 46.9 46.8 46.2 44.3 Greece 23.5 21.1 29.7 30.5 35.9 37.0 38.2 40.2 43.7 42.1 43.0 43.7 44.8 Belgium 36.3 39.1 49.3 50.7 55.3 55.5 55.4 54.4 54.1 53.5 52.3 49.8 48.0 Luxembourg 37.3 36.1 52.5 54.8 58.5 55.8 55.1 51.8 51.1 51.7 52.3 50.9 50.1 France 40.3 38.3 45.0 46.1 48.7 50.4 51.4 52.1 52.2 51.8 51.8 51.2 50.5 Netherlands 43.9 45.8 55.8 57.5 59.7 61.6 62.2 61.0 59.7 59.4 60.1 58.5 56.9 Denmark 36.3 42.1 53.2 56.2 59.8 61.2 61.6 60.3 59.3 56.0 58.3 58.3 57.2

Sources: Figures until 1987 (or 1986 in Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal and Spain) are taken from Table R.14 of the Organisation of Economic and Cooperation publication, Economic Outlook, December 1989. Figures thereafter are calculated by assuming that the share of government outlays as a share of GDP behaved in the same way as the share of public consumption as a share of GDP and using the data for public consumption and GDP in the December 1989 OECD Economic Outlook. The only exception is the UK where the figures for 1988 and 1989 are the ratios of general government expenditure (excluding privatisation receipts) to GDP in the fiscal years 1988/89 and 1989/90, as given in the November 1989 Autumn Statement.

spending in these countries is perhaps best interpreted as a move towards north Euro- pean norms of welfare provision, following the replacement of right-wing military dic- tatorships by democratic and often left- leaning governments in the late 1980s. Here, exceptionally, was a process of fiscal harmonisation in the Europe of the 1980s.

But it is the British position which is perhaps most extraordinary. It is clear that the Thatcher Governments' ambition to Curb the state's role in the economy has already led to a definite contrast in econo- mic structure between Britain on the one hand and France, Italy and all of northern Europe except West Germany on the other Whereas public spending today is above 50 per cent of GDP in all these countries, it is under 40 per cent in Britain. But that is not the end of the matter. Future trends in Public spending will differ markedly be- tween Britain and most other European countries and are likely to widen the gap in the public sector burden.

There are at least three reasons for expecting the trends of the mid- and late 1980s to last into the early 1990s and Possibly even longer. The first is that the British Government is running a budget surplus, whereas other European govern- ments have budget deficits. As a result Britain is repaying its national debt, the ratio of public debt to GDP is falling and so also is the ratio of debt interest to GDP. Debt interest is somewhat different in character from other items of public ex- penditure, but it is still public expenditure. Because public-sector finances are in such good shape today, the strain of servicing Public sector debt in future will be lighter. A virtuous circle is at work.

In the rest of Europe the persistence of deficits has denied governments this advantage. In West Germany and France Public-sector finances are not a very great policy problem, but there is little prospect of achieving the same gains as Britain from a reduction in debt interest costs. Else- where in Europe the condition of public- sector finances is more unhealthy, and in one or two countries there is a serious risk that debt interest costs will spiral out of control. Italy faces one of the worst dilem- mas. Its national debt is now roughly equal to GDP. With interest rates typically above 10 per cent, debt interest exceeds 10 per cent of GDP.

In fact, public debt is about 30 per cent of GDP in Britain and the ratio has been falling by about 2 or 3 per cent a year since the mid-1980s. If the Italians cannot im- prove their public sector finances soon, the cost of servicing past debts will prove a long-term fiscal handicap compared to the rest of Europe. Italy will be at a particular disadvantage compared to Britain.

Secondly, Britain has a different system of pension provision from the rest of Europe. In this country over half of pen- sion payments are funded by the private sector through company schemes, personal retirement plans and the like. In the rest of Europe; however, most pensions come from the state and are distributed on a pay-as-you-go basis. (In other words, they are paid not from a fund set aside specifi- cally for the purpose many years before the pension liabilities fall due, but from gener- al government expenditure in the year concerned.) This difference ought to lead, systemati- cally and permanently, to a lower share of government spending to GDP in Britain.

But there is a further consideration which will give Britain a special advantage in the next two decades. Whereas the proportion of the elderly to the total population will be rising steeply in most of Europe, it will be broadly stable in Britain. Because most European countries therefore face a steep increase in pension payments, the mis- match between the low cost of state pen- sion provision in Britain and the high cost elsewhere in Europe will be aggravated.

Finally, Britain spends a higher propor- tion of its GDP on defence than any other European nation (except Greece), partly as a legacy of its former status as a great power and its retention of the nuclear deterrent. If the present wave of reform in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union is consolidated, defence spending will be cut across Europe. A country such as Britain with an above average level of defence spending should benefit particularly.

In short, there is a high probability that in the mid-1990s the share of public spend- ing in GDP will have been lowered to almost 35 per cent, and certainly will have remained under 40 per cent, in Britain, while all the rest of Europe is stuck at over 45 per cent and some countries are in the band of 55 per cent to 60 per cent.

Of course, the argument is conditional to some extent on Britain's future political complexion. The change in Britain's posi- tion on this measure of economic structure is clearly the work of the Thatcher Govern- ments and is one of their main achievements.

But what would happen if a Labour gov- ernment were elected in 1991 or 1992? Any new left-wing government would be strongly tempted to use Britain's diverg- ence from the European average as a justification for large increases in public expenditure. The difference between Bri- tain and the rest of Europe would soon narrow and perhaps disappear.

This is possible. Much does indeed depend on the outcome of the next general election. However, the success of the Thatcher Government in cutting the public sector down to size has already been a great influence on the debate about Europe's future. M. Delors must be well- aware that, if current trends are main- tained, his vision of a fiscally harmonised and monetarily united Europe just cannot happen. If the share of government spend- ing in GDP is much lower in Britain than in the rest of Europe, it is unrealistic to expect tax rates in this country to be the same as elsewhere in Europe. On the contrary, Britain is likely to favour fiscal competition, knowing that low tax rates will encourage inward investment and the immigration of skilled professional people.

Advocates of full British endorsement of the Delors Report say that, Unless Britain is more positive about European monetary union, we run the risk of 'missing the boat'. They warn that there could be a two-speed Europe in the 1990s, with an inner core of countries moving faster towards integra- tion than sceptical slow-coaches on the periphery, including Britain. Several politi- cians holding this view, notably Lord Jenk- ins and Mr Michael Heseltine, appear to believe that industry and finance will be increasingly located in the core countries. They fear that Britain will be marginalised by its more dynamic neighbours.

They have not bothered to check the facts. The truth is that Britain has attracted far more inward investment, in both manu- facturing industry and financial services, over the last five years than any other European country. Its abstention from the exchange rate mechanism of the European Monetary System does not seem to have worried foreign businessmen at all. But it cannot be denied that, if Mrs Thatcher's policies continue, the 1990s will see a two-speed Europe. A lowly taxed, lightly regulated and debt-free Britain will out- pace the highly taxed, heavily regulated and debt-burdened nations of the inner core.

Previous page

Previous page