ARTS

Architecture

Jones the Baroque

Richard Hewlings

Labels are insignificant things unless they are wrong. The least consequential

feature of a house is the number on its door, unless it leads you into No 6 in the belief that you enter No 7. The label on Inigo Jones is 'Palladian'. After any pro- longed study of his architecture, this name does not matter. But it matters somewhat on being introduced to it, and greatly if the label is wrong, which it is.

It is undeniable that Jones was pro- foundly influenced by Palladio. So was the Baroque architect Bernini. But if so, what sort of architect was Palladio? Please . . . not 'Palladian'. Such procedures make taxonomy meaningless. For Jones students the presumption has always been that Palladio was an architect of the High Renaissance. That was easier to sustain for followers of Rudolf Wittkower, who in 1947 identified High Renaissance architecture by a particular system of proportion. That theory was delightful to practitioners of the Modern Movement, who claimed the same distinction for them- selves, and thus an apostolic succession. But scholars have for some time been dubious, and Palladio's use of such a System was comprehensively rubbished by Deborah Howard and Malcolm Longair in a devastating article in 1982.

Without it, it is difficult to explain Palladio as a High Renaissance architect. High Renaissance architecture was Florentine and Roman, and you have to be generous to maintain that it flourished after 1530. Yet Palladio worked further north, between 1550 and 1580: the wrong place, at the wrong time. Many of Palla- dio's motifs were taken from Raphael and his followers in Rome, people who are usually styled Mannerists, and Palladio was in some senses a Mannerist too. What Would we recognise as his apparent ambi- tion and what as his obvious legacy? His ambition was a determination to recreate the antique world, even if occasionally in a manner which is somewhat artificial. His adopted name, his membership of the Accademia Olimpica, his neo-Vitruvian treatise, his diligent archaeological record- ing and his Romanised churches and farms indicate his principal purpose. It was a Purpose common, in different ways, to Peruzzi, to Serlio, to Labacco, to Pirro Ligoria, to Vignola, to Alessi and to Pellegrino Pellegrini. Historians agree in calling these men Mannerists too. His legacy is the application of the temple front to private houses. His treatise emphasises the need for decorum or appropriateness, Which means that ornament, symbols or forms appropriate to one building type Should not be employed on another. Yet

the application of temple fronts to private houses pays little attention to this concept, however beautiful the result. Beautiful effects at the expense of principle are a characteristic of Mannerism. So are artifice and ingenuity. There is something artificial about houses with temple fronts and some- thing ingenious about the effortless way Palladio achieved the combination. Some- thing Mannerist, in my view.

The reaction to Mannerism is called Baroque. Baroque art revived the Renais- sance attention to the function of a work of art. In painting and literature this means greater attention to the subject matter, thus greater naturalism in painting, sim- plicity in literature. In architecture it also means simplicity, in order not to distract the viewer from the buildings' purpose; the latter expressed by another revived Re- naissance concept, that of decorum. These criteria — functionalism, naturalism, sim- plicity and decorum — were adapted from contemporary literary criticism, itself strongly biased towards Aristotle's Poetics. Their adoption led ultimately to accept- ance of the entire Aristotelian package, of which the feature which went most radical- ly beyond Renaissance ideas was the con- cept of unity. In architecture this means that the parts were subject to the whole, and could not be subtracted without des- troying it. This is as alien to the agglomera- tive nature of Renaissance architecture as functionalism, simplicity and decorum are to Mannerism. Unity is also a logical extension of functionalism, since an indi- vidual part which acquires a separate identity begins to look irrevelant, while a unified composition can be unified to a single purpose.

English architecture, too, conforms to this historical pattern. It is usually pre- sented as veiled in Gothic mist until c.1620, when Jones introduced 'Palladian' archi- tecture, traditionally interpreted as High Renaissance architecture, but now over 100 years behind its cue. It is of course true that English architectural patrons missed the High Renaissance, but not true that they missed Mannerism. The court architecture of Henry VIII did not resem- ble Raphael's or Palladio's, but it did resemble the Villa Medici or the School of Fontainebleau. The influence of the Man- nerist architect Serlio began to be felt in Elizabeth's reign, and so did that of the northern Mannerists, who, even if not Italian, were neither ignorant nor crude.

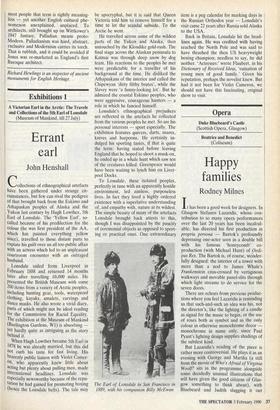

First elevation for the Prince's Lodging at Newmarket Palace, Cambridgeshire, 1618-19 They produced the turreted and pinnacled architecture of contemporary Denmark, Austria, France and Spain. Foreigners from most corners of the Continent would have been unlikely to regard England as either backward or insular in the later 16th century.

It therefore follows that if Jones mod- ernised English architecture c. 1620 he would not have done so by introducing either the High Renaissance or Manner- ism. The former was well-outmoded. The latter was well-established. There is little doubt that Jones wanted to be modern, allowing for the apparent paradox that modernity in Jones's day was partly reg- istered by a knowledge of antiquity. All the important foreign architects of the genera- tion preceding him are echoed in his work — not just Palladio, but Michelangelo, Vignola, Sansovino, Scamozzi and de l'Orme. It is clear that this is how his contemporaries saw him, not as the pro- tagonist of a single school of design, but as a polymath on the Italian model. George Chapman called him 'our only learned architect'. Edmund Bolton wrote to him that he gave 'hope that sculpture, model- ling, architecture, painting, acting and all that is praiseworthy in the elegant arts of the ancients may one day find their way across the Alps into England'.

Bolton's observation also suggests that Jones wanted English architecture to con- form to foreign taste. Jones undoubtedly prided himself on his particular familiarity with Italian art: the Papal Nuncio de- scribed Jones's undignified eagerness to be the first to pass judgment on an Italian painting newly arrived at Court. Nor had anyone else had an equal opportunity to familiarise himself with developments abroad. By 1615 Jones had spent at least five years in Italy. He made an unknown number of trips there, of which the small- est is two. He made two trips to France. He had been employed by the display- conscious King Christian IV of Denmark. He had visited the two most artistically innovative courts of the early 17th century, that of the Emperor Rudolf II in Bohemia and Hungary, and that of the Elector Frederick of the Palatinate at Heidelberg. This abundance of foreign experience was exceptional. James l's reign was not the age of the Grand Tour. Gentlemen rarely went abroad, except in the service of the Crown, and artisans never. For another 100 years no English architect rivalled Jones's experience. Wren spent only a few weeks in Paris, once. May visited the Low Countries as a refugee, Vanbrugh as a soldier.

Whatever the climate of opinion was abroad, it would therefore be surprising if Jones overlooked it. My contention is that he did not. I suggest that what should be identified as the principal innovatory char- acteristics of his architecture, decorum and unity, are those which are the critical

characteristics of Baroque, as defined above.

Decorum, as expressed by Jones (and conspicuously not by his Elizabethan pre- decessors) meant, first, appropriate use of the orders. When Jones designed a stable it was in the Rustic order. A garden was entered by a gate somewhat more polite, but still in the primitive Tuscan. A noble- man's palace was entered through the stern and authoritarian Doric. A king's ceremo- nial hall and the choir of a cathedral were entered via the more elegant Ionic. The Queen's House was ornamented with the feminine Corinthian. A triumphal arch was decorated with Composite, most splendid and festive of all.

Decorum had wider applicability. A royal palace announces itself by the use of a triumphal arch motif, while a row of terrace houses occupied by a number of people approximately equal in status has scarcely any points of emphasis at all. A church is expressed as a temple. The Queen's Hearse personifies her in the attitude of the Queen of Heaven. The King's Hearse assumes the form of an imperial mausoleum.

The individual parts of the design are also subject to the rules of decorum. Of all Jones's contributions to English archi- tecture, his most influential was the structural and functional metaphor by which he divided the storeys into base- ment, piano nobile and ,attic. The base- ment's supportive role (structurally) and servile purpose (functionally) is expressed by rusticated masonry and absence of ornament. The piano nobile's ceremonial purpose is expressed by its size and its pedimented windows. The insignificance of the attic is expressed by its smallness.

Jones divided the storeys thus for another reason. The second novelty of his architecture was its unified appearance. The basic way of achieving it was by designing one feature as a dominant. Dominant features are not generally a characteristic of quattrocento architecture, nor of Mannerist architecture, either in Italy or in England. But Jones's buildings, like his design for the Prince's Lodging, Newmarket, characteristically have a dominant piano nobile in the vertical plane, and, in the horizontal plane, a centre emphasised by an applied portico. This is true in plan as well as in elevation. Jones generally provided some form of dominant recession or projection, some- times quite modest, asat the Banqueting House, sometimes generous, as at Stoke Bruerne. Such modelling designed by any other architect would universally be re- garded as Baroque. There is no reason to deny this identification to much of Jones's architecture also.

This is more than a piece of conceptual refinement. It matters what label Jones wears. At the current magnificent exhibi- tion of his drawings at the Royal Academy the product is marketed as 'Palladian'. To most people that term is rightly meaning- less — yet another English cultural phe- nomenon unexplained, unplaced. To architects, still brought up on Wittkower's 1947 fantasy, Palladian means proto- Modern. Palladianism was hard, abstract, exclusive and Modernism carries its torch. That is rubbish, and it could be avoided if Jones was re-marketed as England's first Baroque architect.

Richard Hewlings is an inspector of ancient monuments for English Heritage.

Previous page

Previous page