MORE OF THE TORY PREROGATIVE.

ft Pants, 24th December 1834. Neserait-ce pas on despotisme, one to gonvernement on Is Roi polo.rait dire : Voila la volunte de mon people, mais la mientte lui est coutraire, et c'ebt la mieune qui revandra ?"—.Diseours de Mirabeau sue le Veto (ler Septre U;S9). "' The n hole power of the State. the affairs of this great and free community, are transferred in a moment from one Minister to another of diametrically opposite maxims of policy. without note or preparation, with no ostensible cause, by a movement as occult and precipitate as a counter revolution hatched in the Seraglio." —Scipzio's Letter to the Spectator (13th Dee. 1830.

- UNDOUBTEDLY, Sir, the responsibility is great which that individual assumes, who by the act, whether of his pleasure or his judgment, changes in an instant all the relations of a great people with surround- ing states, and arrests the current of hope that was running through the bosoms of its active, ardent, and intelligent millions. Yesterday, we were at peace with ourselves and with the Government ; although we were far from discerning in its march that steady and vigorous deter. mutation towards the common weal: which a national Ministry might Live been expected to give it. We were not satisfied, but we were withoet apprehension ; the direction was towards good, though the movement was vacillating ; and we were not disposed to belie our British reputation for longanimity by insisting on weeding out in a ses- sion the whole multitude of tares hy which the national harvest is deaked. If the men who sat at the helm were riot powerful for good, they were not suspected of a disposition to evil ; if amelioration pro- ceeded slowly, or was stationary, it was not retrograde. The men were trusted because they were our la m ; we said their heart is right with mu heart ; if they will not or e.ainot keep pace with the rapidity of our step, we will accommodate it to the tardiness of theirs ; and, 'hough we burn and blush to see abuses still growing in rank luxuriance in free and Protestant England, which even despotic and Papal states heve been obliged to cut down or extirpate, we will not by our preci- pitancy cause our weak brethren to offend, but console our impatience by reflecting, that though a few years are much in one man's existence, they are an inconsiderable quantity in the existence of mankind. They who batten on the garbage of this rank corruption shall gorge without molestation and without misgivings ; their corpulent sumptu- osity shall be respected—the gills of those brilliant "diners out" shall net be one shade less purple than before—the gloss of their sleekiness shAR not be dimmed by the projected shadow of events to come. This generation of fleas shall suck their fill till they drop off from repletion : ear care be it to provide that no lank and hungry swarms succeed in their place. Thus they thought and felt at home : abroad, though men had ceased to throw Westward looks to descry the oak leviathans that were to re- port loudly of the Ocean Queen in that recess of the deep which the great Despot has converted into a basin for his private use, yet their feefings were amicable, their respect was coneiliated, their hopes were encouraged. Old England, they said, is renewing her youth ; and when she has east her slough, she will sine forth in the brightness of her Revolution days. Then, when the grand suit of Right against Might shall come to a decision, her voice will be raised in our behalf, her sword be thrown into our scale. England, they said, in her island den, is no longer the watch-dog of the Holy Alliance—the three-mouthed, triple tongued Cerberus, that

Con Ire gob ° canivamente later Sovra la genie cite quivi sanamersa"

wet prostrate nations sunk in slavery. She is once again Europe's better genius, that high in her far Western home holds up beyond des-

. reach the sacred fire at which we will one day light our torches. She has abjured dondeation, and is content to be free. She has en- tend on the ways of' reformation, and her palls are peace. Her vic- tories are the achiese tents of industry and intellect. She has put ism n the men of blood, and has eschewed along with them violence aild cupidity. Her prtion is no longer cast us ith tyrants; if her sword is not with us, ler heart and voice are, and that is much; for the days am coming whin brute force shall stand rebuked before morality, and the seas: acre of a people be as ignominious as the murder of a man. Thus they thought and felt abroad. Otte man's act has changed all tins; one man's ?pleasure has converted security into anxiety, confi- de:4m into distrust, friendship into aversion, good-will into rancour, and.calm into the swelling that prcsages a tempest. The Dutchman is arming behind his dykes ; the German gang is preparing a decisive pto- tocol for Luxemburg; Belgium is looking to France for assistance ; and France, already half-roused by the WELLIKGTON flag, is destined, as of old time, to defend herself by aggression, and to be accused, as before, by the Tories, of hatching the storm which they themselves have brewed, and of which they are the dmmons. Snch and so great is the conflict preparing on the Northern frontier. For the South, the pub- lication at tins juncture in the Moniteur of the additional articles of the Quadruple Alhance, is generally understood as intended to test the sin- cerity of the late quasi-manifesto (which declares the intention of the ToryGovernment to observe religiously " all existing engagements with Foreign Powers, without reference to their original policy, " as though even Sir ROBERT PLAUSIBLE could reconcile contradictions), and to point out. to the world the good faith that fulfils an article by which Great Britain is bound to assist the Spanish Government with a fleet on the coast of Spain, by detaining vessels laden with arms in dal of that Government on the shores of Britain. The first overt acts- of foryi.sm in favour of Spanish Carlisin will necessitate a crossing of the Bidassoa by the pantalons rouges ; and this passage, like that of the same pantalons rouges over the Belgian frontier, will open out a grand fury chorus of bell-wethers in England so that this last exercise of the derogative Las, in the midst of a 1.tofound peace, exposed Great Britain to two scarcely avoidable risks of a general war. ' At home, the prospect is not more assuring or consolatory. The Nation was looking forward to a pacific adjustment of differences, and a gradual extinction of iniquities : the perspective was long, but the close therefore was the tiny and magic landscape seen through the telescope reversed. Men bore with the foulness of the foreground, because they could repose their eyes on the green speck in the distance. The speck is blotted out ; the vista is shut up ; men's eyes have nought to dwell on but the slough around them, and they wax wroth to be for ever wading in the mire. Was it well chosen to prefer to the friendly burn of the industrious swarm, the monotonous and interested buzzing of the drones ? Was it well advised to lay an adventitrous hand on the ark, like some unwitting child, as Scorr would have said, that has in- advertently touched a vast machine, and is appalled by the whill and clatter of the infinite complication of wheels and cylinders which it has set in rapid motion ? He had need be able to look Apo meow, ass tknerow, from whose actions a movement may spring reach- ing to the world's end, and extending to remote generations. Was it forgotten that this was a Ministry placed in power by the People—the first they ever so placed ; and that the People respected its own work, though it confessed the workmanship might have been better ? " If it is weak," said they, "our sympathy shall make it strong ; we will give it our countenance because we have need of its countenance." What the People have no hand in making, they heed not ; and a thousand removes might have been made, as heretofore, without a question why-. It concerned them nought who was in or who out—whether Whig or Tory held the reins, when their part was only to suffer and endure both alike. But these men were put in for our good and to do our bit-Mess; and others have been substituted for our hurt and to do the business of our enemies. This is different; and the difference should have been considered. It is a difference which cannot be neglected in the calcu- lation; and the summing up may give a result wide of expectation, a tremendous error in the total amount.

It is an unhappy propensity of political men to shape their conduct *.tat• er the example of their predecessors, without any reference to actual circumstances, or any consideration of those changes in public feeling which call for new maxims of policy. " I have constantly observed," says BURKE, " that the generality of people are fifty years at least be- hindhand in their politics." This sudden substitution of black for white, this brusque movement of bon plaisir, this declaration of war in the midst of profound peace, is at least a century behindhand ; and reminds one of French absolutisme in its wanton days, when the Sove- reign discharged a Minister as he turned off a valet. " The King," writes DIDEROT, in allusion to a recent Ministerial resolution under Louis the Fifteenth, "is said never to show his Minister so serene and open a countenance as on the eve of his disgrace. . . . However, M. DE L'AVERDY is wonderfully well considering : he has his retiring pension of 20,000 francs; lie has turned away his man-cook and taken a woman-cook ; he plays the poor man to admiration ; and leaves the idle boys in the street to sing to the tune of the Bourbonniuse,

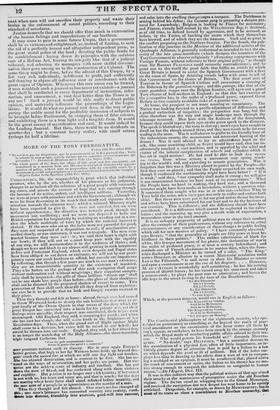

"Le Roi Dimanche lilt a l'AvertlY. flit i l'Averdy, Le Itoi Dimanche flit is l'Averly. • Vat-en

Which, at the peseta moment, would run in English as follows : The King said on Sunday.

Said he to Melbourne, Said he to Melbourne, The King said on Sunday, Said he to Melbourne, " Get you gone on Monday."

The Continental philosophers of the eighteenth century, who spe- c.ilated on government as something as far beyond the reach of prac- tical amendment as the constitution of the lunar states (if there be any), appear, nevertheless, to have been struck by the strange anomaly which the Royal mode of conducting public affairs offered to their rea- son. " Who would govern Isis household so?" demands MONTES- QUIEU. " No doubt," says " but a naturalist devotes to in-

finitely examination of a physical fact, often of little importance, an greater degree of attention than is paid by a Sultan to a law

on which depends the good or ill of millions. But if the latter em- ploys less time in drawing up his edicts than a man of wit in compos- ing a madrigal or an epigram, it must be recollected that, placed above the reoch of resentment or satire, the Sultan on his throne has no mo- tive strong enough to vanquish the indolence so congenial to human nature."—De t Esprit, Disc. III. It was in this indirect way that the political writers of that age aimed their attacks at the wantonness of prerogative under the old Bourbon regime. The Su:tan stood as whipping-boy to the Grand Monarque, and received the castigation due to a despot too near home to be openly criticized. Despotism, for example, as drawn by AIONTESQUIEU, basin most of its traits so close a resemblance to Bourbon monarchy, that it is impossible not to believe that the author has put down to the 'Sultan, or the Pope, or Morocco, all that was too strong and too true for his chapters on Monarchy. " It is said that a Pope' penetrated with a sense of his incapacity, refused at first to accept the Pontificate ; but his scruples were at length overruled ; and having committed to his 'nephew the entire management of affairs, he was heard to say in ad- miration, I could not have believed it was so easy !" To which the water under Du BARRY and the Parc-aux- Cerfs gravely adds—" So it is with the Oriental Princes. Drawn from the Harem, where the eunuchs have corrupted their hearts and blunted their faculties, and placed on the throne, their first feeling is one of astonishment ; but having named a Vizier, and abandoned themselves to the indulgen- cies of' the Seraglio, and the adoration of a court that worship their caprices, they find it easier than they could have imagined." But there is not an Oriental human nature distinct from Occidental human na- ture ; what is true of the one, cannot be absolutely false of the other : all the world over, men are more or less indolent, reckless, self-opinion. ated, and selfish ; and undue influence personified in a nurse, a wife, a mistress, a valet, a peer of the bedchamber, a law lord, or a bishop, is the vizier of the modified or limited monarchy.

Where, however, all is governed by bon plaisir, and the subject is a slave, it is of little importance in what breast the absolute pleasure resides. No one cares to inquire whether the dissolution of Poland be chargeable on the Czar or the wife of the Czar: The bowstring is the same to an unhappy Pasha, whether it come from the Sultan or his mistress ; and though a few piouder spirits may be dainty in the choice of oppression, and prefer the iron heel of the Soldan to the *slipper of his wife, the oppression is equally heavy on the mass. But in govern. ments where people have taken precautions against the exercise of irre- sponsible or at least unrecognized authority, and where, in consequence, affairs are conducted on the supposition that they are safe from any sudden ebullition of spleen or caprice, this chopping and changing of the wind is fraught with serious dangers, and productive of wide con- fusion. When thought is extinct in the breasts of men, they may be driven like beasts of burden and the driver change his mind without their heeding it more than the wind that whistles-oyezthem. But where thought is busy in every man's heint, 'and men apply their thoughts to the business of government as their own business, and to acts of prerogative as to those of an agent deputed to act in their behalf —" for the prerogative of the King is the property of the nation "- they prick up their ears, and demand the why and the wherefore ? The wain was moving—slowly enough, God knows, but it was moving ; we were contented with our leaders, and quietly waiting for what the future should bring us of good ; when behold, all on a Monday morn- ing, our leaders are cashiered, our wain is stopped, our tranquillity at an end, our expectation of good turned into apprehension of evil. We looked for Reform, and Revolution stares us in the face ; for Peace, and War is rumbling all around us,—for the wain has been committed to drivers whose pleasure it has always been to back the horses, and, instead of pursuing the plain and steadfast road, to keep them boggling and plunging In the mire.

It has been attempted, and attempts are making to this day, to per- suade us that this is in the ordinary course of things, and not worth a moment's marvel. A few words seeandunt artem, such as that the King has an undoubted right to exercise his prerogative in the way he pleases, are thought enough to allay the over-boiling of the pot conse- quent on the exercise. Thus the King is pitted against the Nation, as though they weighed in even scales, and the will of the one was an equipoise to the weal of the other. It is forgot that the King is first magistrate for the People, and not for himself; that his prerogative (as understood by all but Doles) is the People's prerogative, to be exer- cised for them, and not against them—which indeed would be cutting a man's throat with his own weapon. The Royal prerogative was intended as a safeguard to the People against rebels, and not to protect cabals against the People. It was especially necessary when a Boroughmon- gering Parliament might, but for a power somewhere to vindicate the independence of at least some part of the constitution, have substituted a close Oligarchy for the more open Aristocracy from which the Reform was to deliver us. But this commending our own sword to our own throat, is what we take unkindly, and makes us reflect with concern on the uncertain tenure of national tranquillity and national consistency. It is not agreeable to us to be let go two years in the way of Reform, and then to be suddenly put about without so much as with your leave or by your leave. It is not agreeable to us, after having lived on friendly terms with free and constitutional states, to be thrust into the company of despots, and to be represented by Lord LONDONDERRY at St. Petersburg, where two years ago we sent Lord DURHAM. If the Tories have not left us a character to lose on the Continent, we at least have one to gain ; and we think that England's good name is our con- cern more than that of a few bespangled persons, who conceive they need no adventitious lustre to recommend them. Simply Englishmen, and neither Sir Thomas, nor my Lord, nor his Highness we have no title to men's respect but the name of our country ; and if this be dis- honoured, we are robbed of that whose loss makes us poor indeed. On the strength of having obliged the Crown and Lords to accept our Reform Bill, we have been saying and thinking that we were citizens; but if we are to fece about at word of command, embrace those we spurned and spurn those whom we had embraced, we are not citizens, but Muscovites, and must not expect any more consideration among strangers than that name procures for him who bears it among us. -Theenlightened and patriotic statesman who rejoices in the name of SPANKIE, would have us be quiet and allow these individuals to work their will on us without molestation. It is true, says he, the drivers

have been changed and the horses' heads put about ; but do you not see that any attempt to rectify this halt in the mud might only splash your. selves. Follow, then, your noses in peace, and be content to see what the blinders put on you permit. Else " what farmer or grazier would raise and send produce to market? what miller would trust the baker ?" Ike. to the end of the chapter. Virtuous Representative of the People ! so we are to remain quiet in the mud, for fear of' sinking deeper; we are to be still in the ditch, lest in climbing out of it we :should tumble into another. This is indeed wisdom worthy of the Bench : health to Mr. SPANKIE, and may he soon get the place he merits! • The bead leader, too, has put forth his ropitory clap on the back, and tells 'is it is idle to kick and plunge where no harm is intended us,.- that ;;;; will make us march in the mire as much to our satisfaction as on the beaten road. and in his direction as agreeably as in our own. He is kind enougii to assure us that he will not touch our Reform Bill, or tamper with what he considers as a "final settlement of a great constitutional question." Sir Joseph Surface may, no doubt, be expected to hang back where danger is visible au bout du compte. But should a time ever arrive when by favour of a Tory-begotten rebellion in Ireland, or a Tory row-general in Europe (and every thing looke promising for both), the ten-pound voters of Great Britain may be disposed of as quietly as the forty-shilling freeholders of Ireland, it were an injury to his reputation not to believe him furnished with a plausibility to show that the final settlement still required to be settled. " No complaisance to our court or to our age can make one believe nature to be so changed, but that public liberty will be among us, as among our ancestors, obnoxious to some person or other ; and that op- portunities will be furnished for attempting, at least, some alteration, to the prejudice of our constitution. These attempts will naturally vary in their mode, according to times and circumstances. For ambition, though it has ever Vie same general views, has not at all times the same means nor ti e 'lune particular objects." " Against the being of Parliament," adds BURKE, " I am satisfied

no designs have ever been entertained since the Revolution ;" and for a good reason, inasmuch as a sham representation has been found the most prolific and convenient mode of squeezing millions out of in- dustry, that was ever devised by the wit or knavery of men. But the power that is good enough to respect the form of representation, has taken no oath to tolerate its reality any longer than it can help it. Professing the most entire respect for the " being" of the Reform Bill, it will deal by it as by the Parliament—i.e. convert it into a machine for extracting fresh millions and preserving the millions got. Every age has its own manners and politics ; the way is no longer to take the bull by the horns, and repeal at a slap. The Tory Government will first get up a " dust " at which it has a peculiar knack, and inspire an alarm, in which it is clever as a Doctrinaire (who in fact is only a sucking Tory); and then it will come down with a plot in a green bag, and challenge the House to say why the qualification should- be ten pounds, why not fifteen, or twenty, &c. ; and the Regans and Gonerils of Reform will reason Mr. Bull from ten up to a hundred, as quickly and peremptorily as the daughters of poor old Lear brought him down from a hundred to ten.

Look to it, all ye who are concerned for your purses, persons, or good name. First in the " brood of hatred," the bell-wether Times is already opening out against Ireland ; the Tories are fighting battles to come, over their cups in Buckinghamshire; the everlasting old Dutch King is meditating an onslaught on Brussels ; your great statesman Duke is arming the Carlists under your noses, and showing what Tories mean by keeping " existing engagements ; " your quondam Holy Alli- ance Ambassador is going to NICHOLAS (before his time) ; all the old rooks are making wing to the wood ; in short, " there's a brew time comin' ; "amid, take Blackwood's word for it, Mr. Bull, you'll get your " fairin• belyve " an you look not to it. Adieu. SCIPIO THE YOUNGER.

Previous page

Previous page