The future arrived in time

Andrei Navrozov

RODCHENKO: THE COMPLETE WORKS by Selim 0. Khan-Magomedov

Thames and Hudson, f40.00

I magine a plucky young fellow from St Petersburg, the son of a washer-woman and a peasant employed as a messenger at a private club, who studies fine art in the provincial university town of Kazan and moves to Moscow, at the age of 23, in 1914. Imagine him, if you will, with the help of the character of Raskolnikov in Dostoievsky's Crime and Punishment: a proud 'student', a young man of talent, whose social position in the metropolis is far higher than his income, and whose expectations are higher still. His rapid social advancement had been made pos- sible by the enlightened, liberal policies of Nicholas II, but he does not see it in this way, and he is right to an extent: his hard work, dedication, and talent did have a great deal to do with his present. position. Still, his dominant mood is one of dissatis- faction.

In Moscow, Alexander Rodchenko meets other young men, many, like the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, immeasurably more talented than himself, but all equally discontented with their lot and seeking `social justice'. They live against the back- ground of an era that will become known as the 'silver age' of Russian culture (although in the époque de la carte de credit we call our own we may prefer to associate it with gold or platinum); but they do not want to accept the existing hierarchy of cultural values any more than they can the political status quo, because this would put the fruit of their achievement, the antici- pated universal appreciation of their uniqueness, out of their reach for too long.

Relief comes from abroad, in the form of a 'futurist manifesto' another young man, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, had published at his own expense on the front page of Le Figaro in 1909. Marinetti has the solution of their dilemma: why not join forces and work to turn the public's taste inside out, smuggling the future — 'our' future — into the present in such a way that our creative experimentation with the means of ex- pression is recognised long before it be- comes definitive? Let us mock, subvert, and overturn the cultural hierarchy of our society and revaluate its values: if the establishment is in control at present, once we have asserted our control over the future, its dictates will be so much ancient history. In short, let us make new clothes for the emperor.

Although the book's author may be offended by this compliment, Rodchenko: The Complete Works is a colourful record of one man's 'revolutionary' initiative. There is little doubt that, like countless other attempts to 'revolutionise' culture, the success of the `constructivism' of Rod- chenko and his peers would have been limited by the enlightened public taste of his day, as is abundantly clear from the historical retrospective devoted to the seminal movement, futurism, currently on view at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (the very words 'historical' and 'futurism' sound funereal in the context of this monumental exhibition). `Constructivism' was saved by an unexpected turn of events.

The autumn of 1917 ended democracy in Russia, and the 'revolution' Rodchenko and his circle had sought to bring about by cultural epatement was suddenly upon them in all its totalitarian immutability. To the new rules of Russia, the 'future' was an important rhetorical, asset, as it is to all usurpers; their propaganda was directed at the 'future' because they, too, needed to control the present with its magic promise. Rodchenko found his true calling, and his fame, in adapting the 'art of the future' to the quotidian needs of Soviet culture prop- aganda.

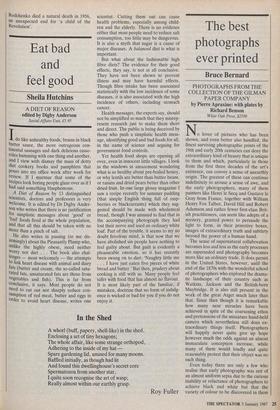

From promotional advertising during Lenin's New Economic Policy to theatre design, from photography to candy wrap- pers and book-jackets, from film to furni- ture; there was hardly anything during the first decade of Soviet rule that Rodchen- ko's hand did not touch. The genius of this man of modest artistic talents lay in his adaptability. His friend Mayakovsky took his own life in 1930; by 1933, Rodchenko was working to immortalise, on film, the construction of the White Sea Canal, Sta- lin's pet project carried out by millions of concentration-camp inmates. Perhaps alone among the friends of his youth, Rodchenko died a natural death in 1956, an unexpected end for 'a child of the Revolution'.

Previous page

Previous page