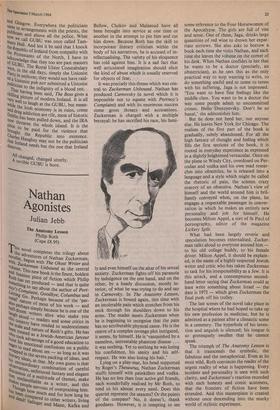

Nathan Agonistes

Julian Jebb

The Anatomy Lesson Philip Roth (Cape £8.95) This novel completes the trilogy about ilavel the adventures of Nathan Zuckerman, with ist, begun with The Ghost Writer and veil Zuckerman Unbound as the centralandfununie. This new book is the finest, boldest Rothhas niest piece of fiction which Philip

'` yet produced — and that is quite

?lesoniething to say about the author of Port- i' s omplaint, Goodbye, Columbus, and etting Go. Perhaps because of the Per' canal' nature of most of his work — and ,also perhaps simply because he is one of the inalf-dozen writers alive who make. you taku.g aloud — readers and some critics in C'his country have tended to underestimate 6! scale and nature of Roth's gifts. He has who ire and as a Jewish-American farceur hou° took advantage of a good education to sl his emotional confusions on a public eager to lead about sex — so long as it was 1/1,1.41313ed in the severe packing of ideas, and hrarY ideas, at that. My own guess is that obis extraordinary combination of careful tii servation, unfettered fantasy and elegant h:scussion of a multitude of themes, make makes unclassifiable as a writer, and this .;,c,es People nervous of overpraising him. h— u° ugh how much and for how long he 4_74. been CoMpared to other writers, living 1113 dead! Salinger and Mann, Kafka and

Bellow, Chekov and Malamud have all been brought into service at one time or another in the attempt to pin him and cut him down. Because Roth has the skill to incorporate literary criticism within the body of his narratives, he is accused of in- tellectualising. The variety of his eloquence has told against him. It is a sad fact that well articulated imagination should elicit the kind of abuse which is usually reserved for objects of fear.

It was precisely this theme which was cen- tral to Zuckerman Unbound. Nathan has produced Carnovsky (a novel which it is impossible not to equate with Portnoy's Complaint) and with its enormous success come gross threats and accusations. Zuckerman is charged with a multiple betrayal: he has sacrified his race, his fami- ly and even himself on the altar of his sexual anxiety. Zuckerman fights off his paranoia by indulgence on the one hand, and on the other, by a heady discussion, mostly in- terior, of what he was trying to do and say in Carnovsky. In The Anatomy Lesson, Zuckerman is bound again, this time with an intolerable pain which stretches from his neck through his shoulders down to his arms. The reader meets Zuckerman when he is beginning to recognise that the pain has no attributable physical cause. He is the centre of a complex revenge plot instigated, it seems, by himself. He is 'vanquished by a nameless, untreatable phantom disease ... it was nothing. Yet to nothing he was losing his confidence, his sanity and his self- respect. He was also losing his hair,' Lying on a play-mat, his head supported by Roget's Thesaurus, Nathan Zuckerman stuffs himself with painkillers and vodka. He has no less than four active girl friends, each wonderfully realised by Mr Roth, to tend to his almost every need. Does this quartet represent the seasons? Or the points of the compass? No, it doesn't, thank goodness. However, it is tempting to see

some reference to the Four Horsewomen of the Apocalypse. The girls are full of vim and sense. One of them, Jaga, drinks large quantities of red wine to drown her expat- riate sorrows. She also asks to borrow a book each time she visits Nathan, and each time she leaves the volume on the corner of his desk. When Nathan confides in her that he wants to be a doctor (precisely, an obstetrician), as he sees this as the only practical way to stop wanting to write, to do something useful and to come to terms with his suffering, Jaga is not impressed. `You want to have fine feelings like the middle class. You want to be a doctor the way some people admit to uncommitted crimes. Hello Dostoyevsky. Don't be so banal,' she admonishes him.

But he does not heed her, nor anyone else. He leaves New York for Chicago. The realism of the first part of the book is gradually, subtly abandoned. For all the high fantasy of thought and feeling which fills the first sections of the book, it is rooted in everyday experience as expressed in a slightly heightened vernacular. Once on the plane to Windy City, overdosed on Per- codan and vodka and his own mad resear- ches into obstetrics, he is released into a language and a style which might be called the rhetoric of pain, the solemn crazy oratory of an obsessive. Nathan's view of himself and the world around him is bril- liantly conveyed when, on the plane, he engages a respectable passenger in conver- sation in which he makes an entirely new personality and job for himself. He becomes Milton Appel, a sort of St Paul of pornography, editor of the magazine Lickety Split.

What had been largely reverie and speculation becomes externalised. Zucker- man talks aloud to everyone around him to his old college buddy, to his female driver. Milton Appel, it should be explain- ed, is the name of a highly respected Jewish writer and critic who has taken Zuckerman to task for his irresponsibility as a Jew. It is this attack, and a contemptuous second- hand letter saying that Zuckerman could at least write something about Israel — the date is 1973 — which gives Zuckerman the final push off his trolley.

The last scenes of the novel take place in the hospital where he had hoped to take up his new profession in medicine, but he is admitted as a patient after a climactic scene in a cemetery. The hyperbole of his inven- tion and anguish is silenced; his tongue is so grotesquely swollen that he cannot speak.

The triumph of The Anatomy Lesson is that it transcends the symbolic, the fabulous and the metaphorical. Even at its most wild, Roth convinces the reader of the urgent reality of what is happening. Every incident and personality is seen with such clarity, and Zuckerman's reaction recorded with such honesty and comic acuteness, that the frontiers of fiction have been extended. And this masterpiece is created without once descending into the murky world of stylistic experiment.

Previous page

Previous page